Tibetan Treasures Series: Amber or Beeswax (སྤོས་ཤེལ)

The cover image of Zhangchal, an important journal of contemporary Tibetan literature.

In 1992, the cover featured a girl from the Kham region adorned with coral and amber ornaments.

སྤོས་ཤེལ་སྦུར་ལེན་ཁ་ཆེ་མོང་གོལ་དང་། །

མངའ་རིས་མཚོ་དང་མོན་གྱི་ཡུལ་ནས་བྱུང་། །

ཁ་ཆེ་གུར་ཀུམ་མདོག་འདྲ་བཟང་བ་དང་། །

དཀར་སྐྱ་ཆུ་སྦུར་འདྲ་དང་དམར་ནག་ངན། །

བརྫུས་མ་ག་བུར་སྤོས་དཀར་བསྡུས་པས་བཅོས། །

ཕྱི་ཡི་རྒྱ་མཚོའི་བཅུད་སྡུད་བཟང་ཤོས་ཡིན། །

འདམ་སོགས་དུག་ཆུ་ལས་ཐོན་ངན་པ་ཡིན། །

སྤོས་ཀྱི་རིགས་ཡིན་བཅངས་ན་གྲིབ་ལ་ཕན། །

"Fragrant Crystal" or "Grass Absorber"

(Both are names for amber or beeswax)

Originating from Kashmir and North Asia,

As well as the lakes of Ngari and the region of Menyul.

Amber with the color of Kashmiri saffron is considered superior,

While amber with the color of grayish-white water insects or black-red is inferior.

Fake amber can be made using camphor and frankincense.

Amber imbued with the essence of the ocean is superior,

While amber from muddy or dirty waters is inferior.

Amber, in general, can dispel negative energies and treat stroke.

—Excerpt from A Summary of Methods for Analyzing Precious Substances (རིན་པོ་ཆེ་བརྟག་ཐབས་མདོར་བསྡུས་གསལ་བ)

By Lama Longdol Ngawang Lobsang (ཀློང་རྡོལ་བླ་མ་; 1719-1794)

Silver Button Inlaid with Gemstones, Made in Ü-Tsang

Late 19th century, Collection of the British Museum

Featuring red coral at the center, surrounded by turquoise and amber.

Multi-Purpose Pastoral Amber Bead Strand

Early 20th century, Private Collection

"Yellow amber produces milk, and red amber produces blood." This is a Tibetan proverb popular in the 19th century. Through existing literature, we can trace the origins of this proverb in the biographies of two Nyingma scholars.

Dorje Drag Monastery (རྡོ་རྗེ་བྲག་), one of the six main monasteries of the Nyingma tradition, has a core hereditary lineage known as the "Dorje Drag Rigdzin" (རྡོ་རྗེ་བྲག་རིག་འཛིན་). The seventh Dorje Drag Rigdzin, Ngawang Jampel (ངག་དབང་འཇམ་དཔལ་; 1810-1844), lost both parents in his childhood and was neglected by his relatives. One day, suffering from a severe illness and lacking breast milk, Ngawang Jampel went to a lake near his family estate. A group of nagas (dragon-like beings) dwelling in the lake offered him a yellow amber the size of an old man's fist (in some texts, the color of the amber is not specified). The nagas claimed that this amber stone could fulfill all the boy's wishes. For the next six years, the yellow amber produced milk whenever the boy needed it and protected him from harm, until he was recognized as the "Dorje Drag Rigdzin."

Similarly, when Do Khyentse Yeshe Dorje (མདོ་མཁྱེན་བརྩེ་ཡེ་ཤེས་རྡོ་རྗེ་; 1800-1866) was a child, he had the ability to teach the Dharma to animals and plants. Soon after, Yeshe Dorje was recognized as the reincarnation of the tertön (treasure revealer) Jigme Lingpa (འཇིགས་མེད་གླིང་པ་; 1730-1798) and was about to leave his homeland (in the Golok region). Before his departure, Yeshe Dorje bid farewell to the animals and plants. Some trees, unwilling to let the boy leave, shed tears of blood, which were so abundant that they enveloped insects. To spread the Dharma to all beings, the young master carried with him the red amber formed from the trees' blood tears and the insects' bodies. This red amber was later revered as a sacred relic.

Beyond the religious undertones of these stories, the idea that amber originates from lakes or the blood tears of trees aligns with modern understanding of this ancient treasure. Transparent amber is called "amber," while opaque amber is called "beeswax." Tibet has a complete and independent system of amber ornamentation.

Do Khyentse Yeshe Dorje

Late 19th century, Collection of the Rubin Museum

Amber with Internal Cracks and Cloud-Like Inclusions

Miocene Epoch, Originating from the Siberian Region

In Tibetan culture, amber with cloud-like patterns is considered a superior ornament.

Prayer Beads with Amber and Precious Gemstones

Late 19th century, Collection of the Rubin Museum

The yellow beads are primarily made of amber.

In Buddhism, yellow beads are associated with the "activity of increase" (one of the four activities), which enhances prosperity, merit, and spiritual progress.

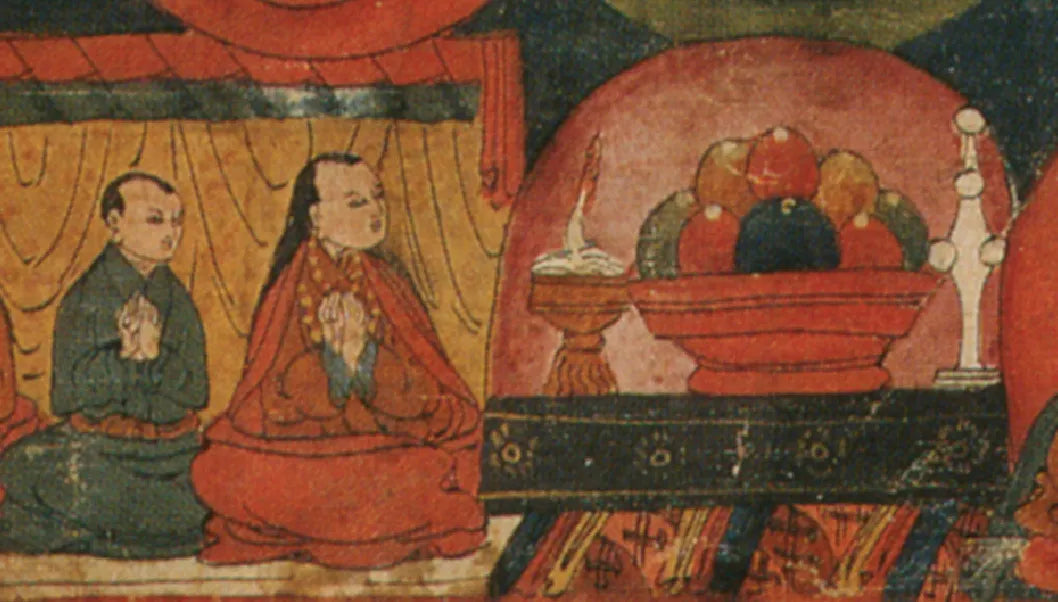

White Tara with the Wheel of Wish-Fulfillment and Attendants, in the Tradition of Atiśa

Mid-16th century, Western Tibet, Private Collection

Detail: A female donor adorned with an amber bead necklace.

Amber Court Necklace

Daoguang Reign, Qing Dynasty (1821–1850), 107 beads

Collection of the Palace Museum

Based on the Tibetan classification of amber (or beeswax) origins and the widely accepted sources of amber today, we can identify three main routes through which amber flowed into Tibet (although Tibet also produces amber, most high-quality amber came from outside the region). Amber from the Baltic region was traded by Eastern European and Arab merchants to Kashmir, where it was combined with local red amber and imitation amber before being transported through western Tibet to central Tibet. In a previous article about Tashilhunpo Monastery, I mentioned the Armenian merchant Hovhannes Joughayetsi, who sold amber to Tibet (as also noted by Western explorers). Amber from Siberia was offered as tribute and gifts by Mongolian nobles and locals to Tibetan monasteries and households. At Labrang Monastery, known as a hub for Mongolian, Tibetan, and Chinese trade, there were vendors selling what was called "Mongolian amber" (མོང་གོལ་སྤོས་ཤེལ) or "northern amber" (བྱང་གི་སྤོས་ཤེལ).

Myanmar, home to the world's most diverse varieties of amber, saw its amber traded by South and Southeast Asian merchants to Himalayan kingdoms such as Sikkim. In fact, the Kingdom of Sikkim established laws regulating amber trade in the 19th century. As amber from these diverse sources flowed into Tibet, its complex symbolism fermented within Tibetan culture, reflected in the two Tibetan names for amber: "Fragrant Crystal" (སྤོས་ཤེལ) and "Grass Absorber" (སྦུར་ལེན). Both the Arab world and ancient China traditionally regarded amber as a core aromatic material. Heating amber to extract its oil produced a fragrance similar to ambergris or pine resin, and the term "Fragrant Crystal" seems to be linked to this tradition. In the broader Eurasian cultural context, amber's natural fragrance was believed to cure eye diseases, dental issues, and dispel negative energies, which is also reflected in classical Tibetan medical systems. Thus, amber embodies a trinity of auspicious symbolism, healing properties, and decorative aesthetics.

Praying Mantis Amber Fossil

Cretaceous Period, Originating from Myanmar

The Sixteen Arhats with Two Attendants: The Chinese Great Monk

Mid-19th century, Collection of the Rubin Museum

Detail: A red coral branch and a wrapped large piece of amber on the donor's table.

"The amber is also damaged and needs to be wrapped for preservation."

Pastoral Woman from Xiahe Region Wearing Amber Braid Ornaments

1936, Photographed at Labrang Monastery

By Harrison Forman

Prayer Beads with Amber and Precious Gemstones

Late 19th century, Collection of the Rubin Museum

In Tibet, amber is typically measured in "strands" as a unit of quantity.

Apart from being used for prayer beads and whole pieces for offerings,

amber is also crafted into strands for palace treasure ornamentation systems.

The materials are categorized as Kashmiri amber, old amber, high-quality amber, and ordinary amber.

Belt Buckle Adorned with Amber, Featuring Antelope and Bear Motifs

1st century BCE to 1st century CE

Nomadic peoples of North Asia, Collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

In Sanskrit, the term Tṛṇagrāhin (तृणग्राहिन्) is often used to refer to amber. This word is composed of tṛṇa (grass) and grāhin (grasping), and the Tibetan term "Grass Absorber" (སྦུར་ལེན) seems to be related to this South Asian vocabulary. From ancient Greece and Egypt to the Arab world and North Asia, people have long known that amber possesses electrostatic properties, allowing it to "attract leaves and fine hairs." In South Asian medical texts and local poetry, this characteristic of amber is extended to symbolize "attraction"—a subtle yet powerful force that influences our reason and emotions.

It is worth noting that the most common Tibetan term for amber remains "Fragrant Crystal" (སྤོས་ཤེལ). However, the concept of amber's "attraction" is also reflected in the poetry of scholars such as Püntsok Pelzang (ཕུན་ཚོགས་དཔལ་བཟང་; 1304–1377) of the Kadam tradition. In his works, the relationship between desire and one's innate nature is likened to the imperceptible pull of the "Grass Absorber."

Berthold Laufer, in his essay Historical Notes on Amber in Asia, remarked: "The Tibetans and the Shan people seem to be the only two groups in Asia who have given amber a broader folkloric role."

Tibetan Official Adorned with Coral and Amber Bead Ornaments

During the Tibetan New Year, 1937, Photographed in Lhasa

By Frederick Spencer Chapman

1 comment

TjuSScS rpVMw eXB XKMIl PmjXVSGf NRLBUpKq