The Beard in Himalayan Portraiture (Part 2) ▎Spotted It from Afar

རྣལ་འབྱོར་མགོའི་རྒྱན་ཆ།

དབུ་སྐྲ་གྱེན་དུ་བརྫེས།

སྨྲ་ར་ཁམ་པ་ཅན།

ཨག་ཚོམ་མེ་འབར་འདྲ།

བདུད་རྩི་འོད་ཟེར་བསྡུས།

འགྱུར་མེད་རྡོ་རྗེའི་ཚུལ།

Hair Tied Up, Beard Brown, Whiskers Like Fire

These are the ornaments of a yogi—

They gather the nectar's radiance,

They reveal the immutable vajra.

—Orgyenpa (གྲུབ་ཆེན་ཨུ་རྒྱན་པ་;1230–1309)

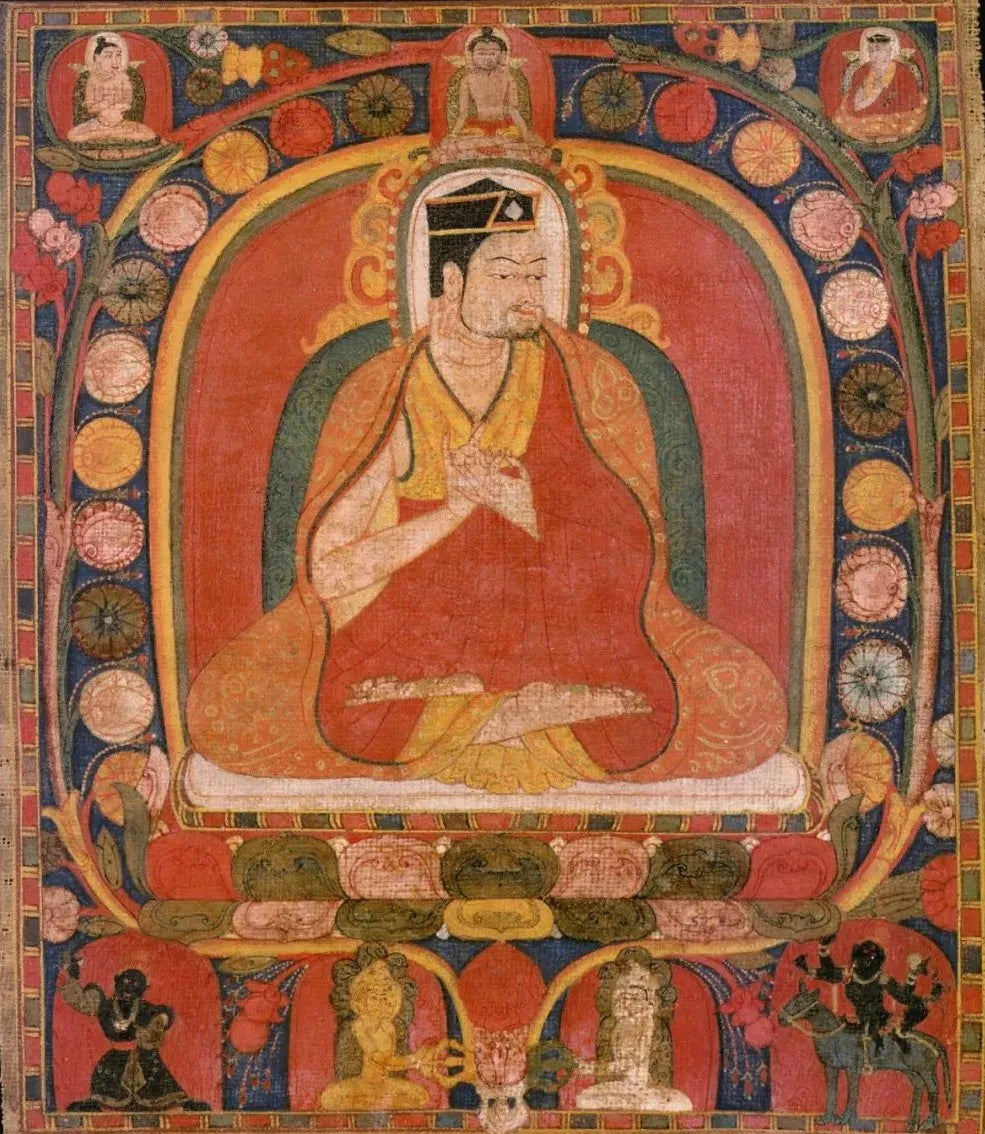

*The Second Karmapa*, 13th century, Private Collection

Detail: The Karmapa's Beard

Detail: Naropa (ནཱ་རོ་པ་)

As the teacher of Orgyenpa, the beard of the Second Karmapa, Karma Pakshi (ཀརྨ་པཀྵི་; 1204–1283), holds a significant place in the origin myths of the Kagyu tradition. The verses by Orgyenpa above praise his teacher Karma Pakshi and the Kagyu's South Asian yogis. As the most miraculous among Kagyu masters, Karma Pakshi’s beard symbolized the profundity of his practice.

When the new Mongol Khan, Kublai Khan, decided to purge Karma Pakshi (it is generally believed that the Karmapa, who had once initiated Kublai, did not support him politically), soldiers dragged him by his beard with a rope. Karma Pakshi declared, *"This does not harm me, but may no future lineage holders grow beards."* (Subsequently, no beards appear in portraits of the Karmapas.)

After a series of miraculous displays and political struggles, Kublai and Karma Pakshi reached a reconciliation. In 1264, the Karmapa began his return to Tibet and continued composing scriptures under the pen name *"Rangjung Dorje" (རང་བྱུང་རྡོ་རྗེ་)*—the very name later taken by the Third Karmapa.

*The Second Karmapa*, 18th century, Museum of Cultures, Basel

Detail: The Karmapa's Beard

Some texts refer to his beard as

"Mountain-Peak Whiskers" (ཨག་ཚོམ་རི་རྩེ་མ་).

Detail: Orgyenpa

Detail: Möngke Khan

Möngke Khan once offered a golden seal to the Karmapa.

Here, the Mongol Khan is depicted in the manner of a Central Plains ruler.

Detail: Distant Mountains and Rivers

Classic Landscape Composition of the Late Karma Gadri School

*The Second Karmapa*, 15th century, Private Collection

The Beard · The Dharma

*The Great Adept Saraha*, 19th century, Rubin Museum of Art, New York

Detail: Saraha's Beard

Detail: The Arrow-Maker Woman

As an emanation of a ḍākinī,

the arrow-maker woman symbolized through the sound of arrows,

leading Saraha to realize the teachings of Mahāmudrā.

Detail: The Consort

Likewise, as an emanation of a ḍākinī,

Saraha's consort mocked him:

"After all your practice, why do you still care only about

the radish curry from twelve years ago?"

These words freed Saraha from all self-grasping

and granted him the supreme realization of Mahāmudrā.

Detail: Ritual Offerings

Common ritual offerings in Karma Gadri paintings—

the lotus and twin fish symbolize:

*"No discriminating mind, thus the true fruit is attained."*

Composed by Situ Rinpoche

(ཆོས་ཀྱི་འབྱུང་གནས་; 1699–1774).

As a forefather of the Mahāmudrā lineage (ཕྱག་རྒྱ་ཆེན་མོ་), Saraha (ས་ར་ཧ་པ་/མདའ་བསྣུན་) often appeared as a wandering yogi (གྲུབ་པ་) and a "mad saint" (སྨྱོན་བླ་). After twelve years of intense meditation, his hair and beard turned completely white.

Many later Mahāmudrā practitioners in Tibet aspired to attain a visage like Saraha’s through prolonged meditation. For instance, Ngawang Namgyal (ངག་དབང་རྣམ་རྒྱལ་; 1594–1651), the Drukpa Kagyu master and unifier of Bhutan, was praised in his biography as *"Saraha in the flesh."*

In short, South Asian ascetics like Saraha profoundly influenced Tibet’s religious veneration of beards.

Ngawang Namgyal, 18th century, Private Collection

Detail: Ngawang Namgyal's Beard

If the yogi's beard tradition stems from Tibetan masters emulating and learning from "South Asian archetypes," then the tertön's beard tradition carries distinctly indigenous religious traits. The emergence of New Terma (Tibetan religious history is broadly divided into Old and New Tantras) is deeply tied to doctrinal disputes over orthodoxy.

The Nyingma school, in its localized form, needed to demonstrate that its lineage was no less legitimate than other schools originating from South Asian mahāsiddhas between the 11th and 13th centuries. Their method was to assert the existence of undiscovered texts from the Tibetan imperial period—termas.

In this context, a tertön's beard in literature often holds two symbolic meanings:His role as a patriarchal figure in familial lineages (as tertöns could be householders);A mark of authority as the discoverer of treasure teachings (the elder custodian of wisdom).

Jigme Dorje, 18th century, Hahn Cultural Foundation

Detail: Jigme Dorje's Beard

Jigme Dorje (འགྱུར་མེད་རྡོ་རྗེ་; 1646–1714)

Founder of Mindrolling Monastery (སྨིན་གྲོལ་གླིང་),

one of the Six Mother Monasteries of the Nyingma School,

revered as "The Long-Life King of Tertöns."

Jigme Lingpa, 18th century, Private Collection

Detail: Jigme Lingpa's Beard

Jigme Lingpa (འཇིགས་མེད་གླིང་པ་; 1730–1798),

founder of a tertön lineage,

redefined the essence of the terma tradition

and expanded the Nyingma heritage in Kham.

If you dreamed of a kindly white-bearded elder saying,

*"Come, let me show you,"*

what would you think?

In the biographical traditions of the Sakya, Zhalu (ཞ་ལུ་), and Bodong (བོ་དོང་) schools,

such narratives exist:

A master (or guru) appears in a disciple’s dream to reveal wisdom,

and the disciple, by remembering the dreamt face,

later recognizes their teacher in waking life.

This unique literary device romanticizes

the origins of guru-disciple bonds.

*Bodong Chokle Namgyal*, 15th century, Tibet Museum

Detail: Chokle Namgyal's Beard

*Bodong Chokley Namgyal*, 15th century, Private Collection

Detail: Chokley Namgyal's Beard

The great translator Chokyi Zemo (བྱང་ཆུབ་རྩེ་མོ་; 1303–1380) was a key master and scholar of the Bodong tradition in its middle period. His niece, Chokdrup Drolma (བྱང་ཆུབ་སྒྲོན་མ་), gave birth to Chokley Namgyal (ཕྱོགས་ལས་རྣམ་རྒྱལ་; 1376–1451), revered as the *"Omniscient Bodongpa."*

In a dream, Chokyi Zemo bestowed empowerments upon Chokley Namgyal and revealed the site for a new monastery—Palmo Choding (དཔལ་མོ་ཆོས་སྡིངས་; established 1410).

In portraiture traditions, their depictions share striking resemblance,

especially in their flowing white beards.

The Beard · The Divine

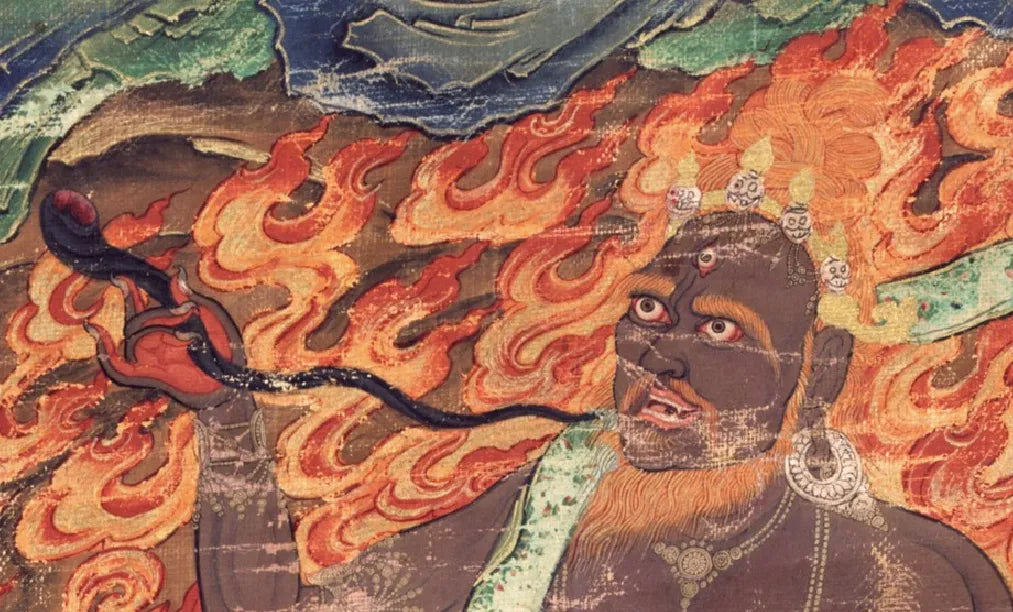

Brahmarupa Mahakala, 17th century

Rubin Museum of Art, New York (Sakya Tradition)

Detail: Brahmin-Style Yellow Beard

Holding a deer-antler horn,

the yellow hue mirrors the beard of Four-Armed Mahākāla.

Detail: Sakya Patron

*Brahmarupa Mahakala*, 18th century

Rubin Museum of Art, New York (Gelug Tradition)

Detail: Brahmin-Style White Beard

The white hue mirrors the beard of a Brahmin sage.

Detail: The Mantrika's Attendant

Brahmarupa Mahakala (མགོན་པོ་བྲམ་ཟེ་) is considered one of the emanations of the Sakya tradition's Four-Armed Mahakala. When the translator Nyan Darpa (གཉན་དར་མ་གྲགས་; 11th century) received the Four-Armed Mahakala teachings in India, a dakini bestowed upon him a dark-complexioned Brahmin attendant—this became Brahmarupa Mahakala.

Upon Nyan Darpa's return to Tibet, the Brahmin manifested as a protector to safeguard the Four-Armed Mahakala lineage. Shortly after, Nyan Darpa’s disciple Dharma Senge (དར་མ་སེངྒེ་; 11th century) transmitted the protector’s rituals to Sachen Kunga Nyingpo (ས་ཆེན་ཀུན་དགའ་སྙིང་པོ་; 1092–1158), the First Patriarch of Sakya.

Both the Sakya and Gelug traditions venerate this protector,

though their iconographic depictions differ.

The Sage, 19th century, Private Collection

*The Sage* (དྲང་སྲོང་) is a classic South Asian archetype—

dwelling in forests and snow mountains,

mastering knowledge and life sciences.

Tibetan medicine often invokes them

to assert so-called "South Asian orthodoxy."

*The Six Long-Life Deities*, 18th century, Robert and Lois Baylis Collection

Detail: The Long-Life Sage

Detail: Amitāyus

Leaning against the Tree of Longevity is the white-haired, white-bearded Elder of Immortality (or the Long-Life Brahmin), who, through millennia of practice, transcends the cycles of life and death—an emanation of Amitāyus.

This archetype appears across Asia:

from China’s Southern Pole Immortal (南极仙翁)

to South Asia’s *Maharishi*,

from North Asia’s ancestral spirit-gods

to the Naxi people’s primordial elder.

Legend attributes to him seven traits beyond mortal reach:

indifference to death, wisdom, merit, luminous mind, fearlessness, transformative power, and universal reverence.

In art, he often holds a mala and staff,

as if recounting the oldest tales—

from nature’s dawn to humanity’s rise,

through all loves, grudges, and the dance of causality.