The Himalayan Chronicles of a Monk of Love ▎Satisfy a thousand desires, or conquer just one?

Samsara (2001) Director: Pan Nalin

Departure and Return

In the movie "Samsara," the main character Das experiences two departures. The first is his departure from the monastery where he had practiced for twenty years, starting from the age of five, venturing into the secular world. The second is his departure from the secular world to return to the monastery. Like a rebirth through nirvana, this Das is no longer the same as before. These two departures perfectly form a complete metaphor for the cycle of life.

Looking back on the past, it feels like a dream. At the end of the film, as Das quietly leaves his room in the early morning, abandoning his beloved wife and children, he sees the illusion of his wife, Pema, appear before him. Lying on the ground, his body contorted, Das is overwhelmed with unbearable pain, tears streaming down his face. At that moment, I thought what Das had clung to so strongly was now shattering and dissipating, as he completed a difficult farewell to his past. It was like the prolonged and excruciating ordeal a chrysalis endures before transforming into a butterfly. And traversing pain is a necessary prerequisite for life to undergo such transformation.

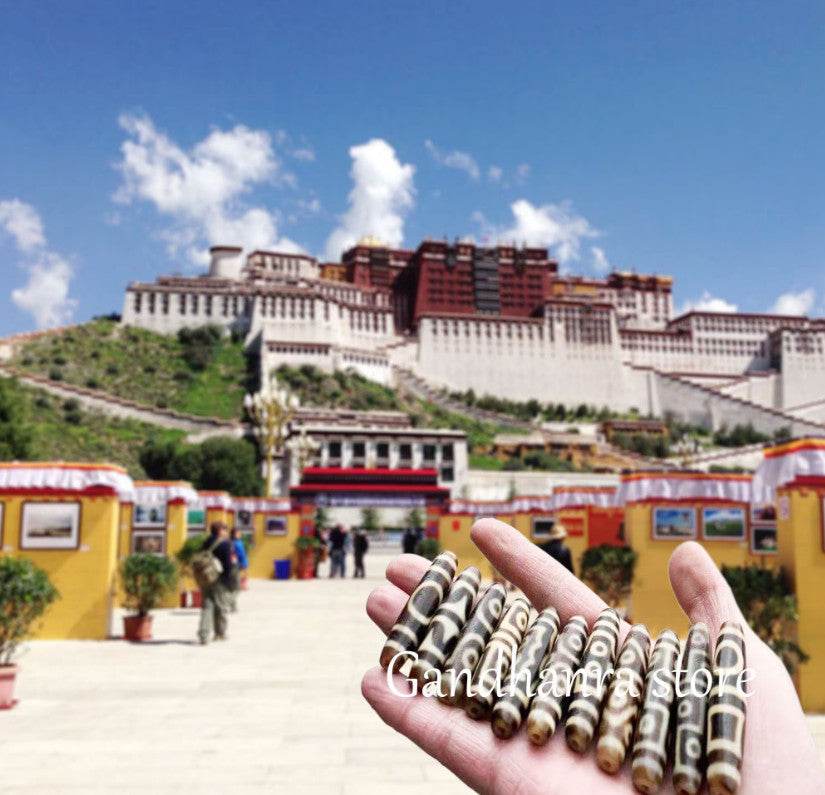

Movie stills

Before one attains rebirth, one must inevitably undergo a heart-wrenching death. Thus, a person lives twice. The first life is one of ignorance; the second is an awakened life, as if reborn with a new body, after traversing the world's hardships, shattering old beliefs, and completing an inner renewal. From this point on, the way one views the world and oneself will never be the same as before.

"Samsara" retells the story of Prince Siddhartha's departure in a modern context. The nested structure deepens the dreamlike quality of the visual art while also evoking a subtle sense of connection between past and present lives.

Prince Siddhartha Leaves the Palace at Midnight and Cuts His Hair

19th Century, Thailand

Lacquer and gold on wood

Collection of the Asian Art Museum of San Francisco

Prince Siddhartha departed from the illusions of luxury and prosperity, while Das in the film left behind a life of monotonous, uneventful ascetic practice. The cause of their departure was a shared skepticism toward their current existence. Unable to reconcile the contradictions and flaws in a life they were expected to accept, they chose to bravely step out of their comfort zones in order to disprove all they had once possessed and grown accustomed to.

Sentient or Non-sentient

The direct cause that prompted Das to leave was his sudden, intense awareness of the stirrings of youthful desire within himself. In this regard, the avant-garde and uniqueness of the film *Samsara* perhaps lie in its direct confrontation with the hidden inner world of a monk. Many films about monastic life that we have access to today focus on the orderly, ascetic routines of monks, while the details and secrets of their existence as human beings—beyond their roles or symbolic identities—are selectively overlooked. Thus, the private lives of monks remain a mystery. People in the secular world have no way of understanding their other side, like the dark side of the moon. We can only satisfy our curiosity through speculation and imagination, and *Samsara* fills the void left by such imagination.

Movie stills

The truth is that even monks in practice cannot ignore their emotions as natural human beings. Stirring desires slowly cloud Das's mind like gathering storm clouds. The frequent emergence of physical urges makes it impossible for him to look the other way. His clarity does not allow him to deceive himself. From this moment on, desire becomes an increasingly powerful enemy, with whom Das must struggle day and night.

Yet there is no need for harsh judgment. How can one find a way to serve both the Buddha and the beloved? Even the Sixth Dalai Lama, Tsangyang Gyatso, was once deeply entangled by love.

As Socrates famously said, "The unexamined life is not worth living." When Das attempted to break free from the disciplined, ascetic life that had suppressed his humanity under strict rules for over twenty years, he discovered the fragility of that existence. Or rather, he was unwilling to ignore his genuine senses and willingly embrace a seemingly tranquil yet illusory calm. That kind of life, at least for Das at this moment, held no persuasiveness. He had never truly possessed nor released his passions, so he could not pretend to suppress these urges with nonchalance.

Movie stills

He had once witnessed a child crying inconsolably after being brought to the monastery by his father, unable to bear the separation from his family. He had also seen his master grow silently angry over his frequent dreams. Every expression of emotion from those around him felt so real. Their status as practitioners did not grant them the ability to remain untouched by emotion.

Men are not plants or trees—how can they be without feeling? It is not a lack of emotion, but rather, having chosen the path of practice in this life, one must abide by its precepts, and emotions must rightfully be restrained. However, for Das, who had never ventured through the seas of love and illusion, the doctrines instilled in him since childhood faced a challenge, and the world of Truman was on the verge of shattering.

Impure Contemplation

The Japanese writer Jun'ichirō Tanizaki once wrote a passage about "Impure Contemplation" in one of his novels. To overcome the overwhelming desire for the opposite sex within him, a man chooses to visit a cemetery under the moonlight to observe decaying corpses. Even the most stunningly beautiful and captivating physical form, once life fades, cannot escape the laws of nature—the body will transform beyond recognition as it decomposes in death. What people obsess over and cling to is nothing but this horrifying truth, too terrible to face directly. This is the practice of "Impure Contemplation." As an important method of Buddhist cultivation, it aims to completely "extinguish attachment to the physical form."

In the film, the silent elder monk attempts to enlighten Das in a similar way, striving to awaken him as he is about to sink into desire. When Das, under the flickering candlelight, flips through the erotic pictures the elder monk retrieves from a box to show him, he is horrified to see the beautiful figures in the paintings instantly transform into skeletons.

Movie stills

What is illusion, and what is reality? The intense attachment to seemingly real beauty feels genuine, yet humans inevitably age and die—beauty is but a fleeting illusion. If the scales of time and space are stretched infinitely, even a hundred years of life pass in the blink of an eye, and beauty turns to withered bones in an instant. Those lost in ignorance cling desperately to the illusion of permanence, and thus suffer greatly, tormented by their attachments.

Yet for Das, who had not yet broken through the illusions of love, the world of desire was a beautiful rainbow suspended above him, a cool oasis shimmering before the parched traveler in the desert. Every genuine pulsation of desire only painted the illusions before him in increasingly magnificent hues. Having never experienced or verified it for himself, he had no way of knowing that the objects of his attachment were merely temporary outcomes born of causes and conditions—outcomes that were far from solid, forever flowing and changing.

Movie stills

A thousand desires

The most moving part of the film is the encounter between Das and Pema. In the boundless wilderness of time, they meet neither too early nor too late—a moment of joy that evokes thoughts of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden at the dawn of creation. A pure and uninhibited romance elevates beauty to its peak, yet also carries a sense of danger and sorrow. For all things are impermanent. Or perhaps it is precisely this impermanence that makes one acutely aware of the existence of beauty, giving rise to attachment and longing.

Movie stills

In his aged and compassionate voice, the master harbored deep pity for his disciple. "I know my karma is not yet complete. I will be reborn again, and we will meet once more. Perhaps then you will tell me what is more important: to satisfy a thousand desires or to conquer one..." It felt like a message from a past life—a way of existence that Das, now deeply immersed in the beautiful secular world, had nearly forgotten on the distant shore.

A thousand desires equate to endless desires, like two mirrors facing each other, reflecting an infinite labyrinth that ensnares one unknowingly, lost in an illusory realm. To conquer one desire, however, means the shattering of illusions—an end that brings clarity and awakening. Finally piercing through the delusion to attain an enlightened mind is to be reborn in nirvana. To satisfy a thousand desires or to conquer one... What is more important? Das seemed to begin questioning the outcome he had once tirelessly pursued.

Movie stills

A drop of water

I remember a detail: Pema threw a branch into a flowing stream. She asked the children, "Tell me, what will happen to the branch?" One child said, "The branch will get stuck in a whirlpool." Another said, "It will hit a rock and break." A third child thought for a moment and said, "It will sink to the bottom and rot." Pema smiled and told the children, "None of that is right. The branch will eventually drift into the sea."

Suddenly, like a flash of lightning, I recalled the mani stone that appears at both the beginning and the end of the film. Inscribed on the mani stone is this verse: "How can you stop a drop of water from ever drying up?" However, the answer to this question is hidden on the back of the stone and is not revealed at the start of the film. Only after Das has struggled through the trials of the secular world and is on his journey back does he instinctively turn over the mani stone he encounters again, finally discovering the answer.

How can you stop a drop of water from ever drying up? Let it flow into the sea. A moment of sudden enlightenment, deep understanding, or a sense of déjà vu.

Movie stills

In the novel "The Story of Migyur" co-authored by the renowned French orientalist Alexandra David-Néel and her adopted son Yongden, I first encountered a phrase with the same meaning: "All rivers flow to the sea." The emotion this line evoked in me at the time remains unforgettable. In this world, a person is like a tiny drop of water, traversing countless perilous and winding journeys, ultimately merging into the sea and attaining eternal peace. This symbolizes a homecoming and signifies a profound reconciliation with suffering. When the spirit is elevated, even the most arduous journey becomes insignificant. The fate of a single drop of water is to evaporate and disappear, yet by merging into the sea, it becomes part of something vast, deep, and infinite, thereby achieving eternity. It is an immensely inspiring phrase, shining like a beacon that brings faith and solace to the heart.

Movie stills

With his innate wisdom, I believe Das must have faintly sensed this at some point in his life—that he too was a drop of water, and also the branch Pema tossed into the stream. Every subtle phenomenon was like nectar watering the obscured seeds within Das's heart. Life is transient; each of us in this world is but a passing traveler. Clinging to love and desire cannot make them linger forever. What people tirelessly pursue, striving to hold onto indefinitely, is nothing more than a fragile bubble. Gradually, Das awakens.

I recall a passage from Hermann Hesse's novel *Siddhartha*: "I had to experience despair, I had to sink to the greatest mental depths, to thoughts of suicide, in order to experience grace, to hear Om again, to be able to sleep properly and awaken refreshed. I had to become a fool again in order to find Atman in myself. I had to sin in order to live again."

Movie stills

Through Illusion, Return to Truth

The monastery of Das appears several times in the film. The most memorable scenes are two: his departure and his return. Before Das leaves, in the pale blue light of dawn, he gazes back from afar at the fortress-like structure nestled in the valley. To me, it feels like a heavily guarded prison, suffocating the vibrant life of Das, who is in his early twenties. Yet, when Das returns after his arduous journey through the world, the same place feels like a comforting home. Like a warm embrace, it waits in compassion and silence for the weary, heartbroken traveler. The sense of severity and terror fades, leaving only familiarity and warmth. The place Das left and returned to is akin to the eternal home each of us will ultimately embrace.

The same scene, the same setting, evokes entirely different feelings. This is because the viewer, following Das's journey, undergoes a subtle yet profound shift in perspective. This brings to mind what defines a classic film. Immersed in the two-hour dream woven by light and shadow, we experience joy, melancholy, pain, danger, satisfaction, and every emotion alongside the characters. When we emerge from this dream, we gain insights, our hearts cleansed, moved, or purified. Our minds are subtly elevated.

Movie stills

Living secluded in a monastery is not necessarily the path, and devoting a lifetime to scriptures is not necessarily true practice. Only what one has truly possessed can be let go with ease. To transcend the world, one must first fully engage with it. Precious enlightenment can only be gained through the hardships of worldly life. Only by traversing suffering can one attain true inner peace.

From the age of five, Das lived a strictly disciplined and secluded life—much like the previous existence of Prince Siddhartha, surrounded by nobility, fine clothes, and lavish feasts. As his personal consciousness gradually awakened and stirred, Das bravely stepped beyond this sheltered sky, venturing into the secular world to breathe fresh air and attain enlightenment.

Movie stills

*Samsara* is a delicate and poetic film, akin to an ethereal parable. Reflecting on it from beginning to end, every metaphorical detail quietly releases boundless energy, continuously renewing, elevating, and breaking through the viewer’s mind. It feels like traversing layers of illusions and barriers, ultimately arriving at truth with sudden clarity. Any single scene, appreciated on its own, holds a rare and profound beauty, like beads strung together to form a mala. With each gentle turn of the beads, we receive deep and enduring revelation.