Genka: A Long-Lost Musical Instrument Reappears in Tibet

Genka

(Collection of Tibet Museum)

“I can't let this instrument die in my hands.”

"I can't let this instrument die in my hands," said Mr. Kharpa Tashi Tsering, nearly eighty-five years old, while tuning the string instrument in his hands. I could detect a complex blend of hope and worry in his eyes. At this moment, he is a national-level inheritor of the intangible cultural heritage arts of Gar and Toeshey Nangma, as well as a widely recognized master of Tibetan folk performing arts. And the instrument he is playing is the Genka, a traditional Tibetan instrument that had been lost for nearly forty years.

Mr. Tashi Tsering performing on the Genka

(Photo: Author)

An ancient musical instrument from Persia

Unlike the local instrument Dranyen, the origins of the Genka are far more complex. Due to geographical isolation, traditional artists of past generations believed that the Genka was introduced to Tibet from the Kashmir region around the same time as the court music Gar(གར།). However, this theory is too vague. After careful research, we believe the Genka likely originated from the traditional Persian instrument: the Kamancheh.

Kamancheh

(19th century, Persia)

The kamancheh is widely distributed across regions such as Iran, Azerbaijan, Armenia, Turkmenistan, and Uzbekistan. Additionally, the craftsmanship and performance art of this instrument were jointly nominated by Iran and Azerbaijan for inclusion in UNESCO's "Intangible Cultural Heritage" list.

A Persian woman playing the kamancheh

(Period unknown, Persia)

The kamancheh has a slender neck and a wooden, bowl-shaped soundbox, typically covered with a membrane made of lamb, goat, or fish skin. The bridge rests on the membrane, and a wooden spike extends from the base to support the instrument while playing. Traditional versions of the kamancheh have three strings, while modern modified versions feature four strings.

A Persian woman playing the kamancheh

(1820, Persia)

A Persian woman playing the kamancheh

(1816, Persia)

Introduced to Tibet

Despite its location in the high inland plateau, Tibet boasts a rich variety of musical instruments and performance systems. In addition to locally developed traditional instruments, there are also numerous foreign instruments, most of which were introduced to Tibet via trade routes spanning the Asian continent. The Genka is a representative example. After its introduction to Tibet, it was primarily used to perform court music (Gar). Its performance and transmission have been managed by the Potala Palace court music and dance troupe. Its form largely retains the style of the kamancheh, and the names of the two instruments are also very similar: kamancheh / Genka (འགན་ཆག).

The Potala Palace court orchestra performing Gar

(1956, included in "The Central Delegation in Tibet")

In addition to the Genka mentioned above, instruments like the yangqin and jinghu are also representatives of foreign instruments introduced to Tibet during different periods. The yangqin first arrived in China's southeastern coastal regions via the Maritime Silk Road and later became widespread in Han Chinese areas. The jinghu was adapted from the huqin during the Qianlong era of the Qing Dynasty and derived its name from its primary use in accompanying Peking Opera. Both instruments were practiced by the renowned Tibetan artist Dorin Tendzin Bumcho during his residence in Beijing in the late 18th century and were later integrated into the traditional Tibetan song and dance art, Toeshey Nangma (སྟོད་གཞས་ནང་མ།), as accompanying instruments.

A lost musical instrument

Ancient musical instruments preserved over thousands of years serve as extremely precious physical evidence in the study of ethnic music history. The Jokhang Temple in Lhasa, Tibet, once housed dozens of ancient surviving instruments. According to local legends, these instruments were brought to Tibet by Princess Wencheng from Chang'an in the 7th century AD.

String instruments from the Jokhang Temple

(Collection of Tibet Museum)

However, according to scholarly research, some of these instruments may have been introduced from Han Chinese regions in the 7th century AD or later, while others are ancient instruments that entered Tibet from western and southern directions during different historical periods, as well as indigenous ancient instruments of Tibet. Their existence clearly demonstrates the exchange and integration of musical cultures from East Asia, Central Asia, West Asia, and South Asia in Tibet.

Plucked string instruments from the Jokhang Temple

(Collection of Tibet Museum)

Unfortunately, after these instruments were introduced to Tibet, they did not develop into a systematic form of performance. Instead, they were sealed away as treasures in monastery storehouses. On the 30th day of the second month of the Tibetan calendar during the traditional "Ser Dreng" (སེར་སྦྲེང་།) ceremony, monks in ceremonial attire would parade through Lhasa, carrying sacred statues, ritual objects, offerings, and musical instruments preserved in the Jokhang Temple for public display. This collection of ancient instruments was included among them. However, the monks carrying these instruments did not know how to play them.

Plucked instruments from the Jokhang Temple at the Serdreng Ceremony

(1957, photographed by Chen Zonglie)

At that time, the elderly Mr. Tashi Tsering served as a dance attendant in the Potala Palace court dance troupe. He, along with other dance attendants, participated in almost every Serdreng procession throughout the 1950s, playing a very important role. He recalls: "During the Serdreng, we performed Gar in front of the Potala Palace. Monks from the Jokhang Temple entered the venue holding ancient instruments, but none of us knew the names of these instruments, nor did they know how to play them. They just plucked the strings randomly, pretending to play..."

Gar performance at the Serdreng Ceremony

The rightmost figure is the seventeen-year-old Tashi Tsering

(1957, photographed by Chen Zonglie)

Tashi Tsering introducing the ceremony at the Serdreng venue

(2016, included in "Oral History of Gar Inheritors")

These instruments, lost to the river of history, may have become a lingering concern for the elderly Mr. Tashi Tsering. Thus, over nearly sixty years, he diligently studied the instrumental music art of Tibet, ultimately becoming a renowned master of Tibetan instrumental music.

Reviving the Genka

The earliest known video footage of the Genka dates back to 1954. Czechoslovak military filmmakers Vladimir Sis and Josef Vaniš stayed in Tibet for 10 months and collaborated with the People's Liberation Army Film Studio (August First Film Studio) to produce a documentary.

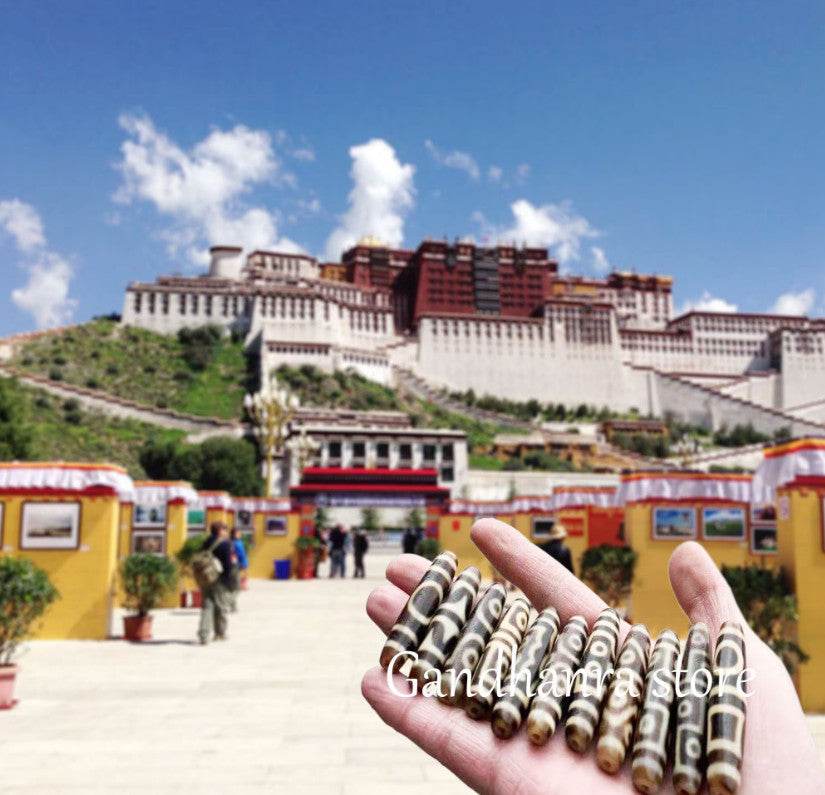

Sis and Vaniš in front of the Potala Palace

(1954, photographed by Vladimir Sis et al.)

During their time in Tibet, the two also recorded numerous musical works, which were later compiled into an album and published in Czechoslovakia. This included a duet piece featuring the Genka and the Dranyen, performed by Dawa Dhondup, a musician from the Potala Palace court music and dance troupe.

Dawa Dhondup holding the Genka

The youth on the far left is Tashi Tsering

(1954, photographed by Vladimir Sis et al.)

In 1954, 1959, and 1961, three conferences themed "Musical Instrument Reform" were convened under the leadership of China's music and cultural management authorities. These conferences brought together institutions for music research, instrument manufacturing, as well as orchestras and folk artists. Among the many instrument reform efforts discussed at these "Three Conferences," one category deserves particular attention: the reform of ethnic minority musical instruments.

Sketch of the Genka before modification

(1961)

During the "Three Conferences," the most discussed ethnic minority instrument was the Genka. Participants addressed issues related to its modification, introducing the instrument before pointing out its shortcomings in craftsmanship. As a result, reforms were carried out by altering the materials and structure of the Genka. Additionally, a "crescent-shaped base" was added to facilitate its performance in various settings. From the mid-to-late 1960s through the 1970s, the modified Genka became a substitute for the violin in major official Tibetan music ensembles.

Sketch of the modified Genka

(1961)

In 1981, at the invitation of the Tibet Autonomous Region Mass Art Center, Tashi Tsering and other former members of the Potala Palace dance troupe began the revival of the Gar art. Among them, Tashi Tsering and Dawa Dhondup standardized the tuning method of the Genka based on its modified design, making it better suited to the performance style of Tibetan classical music.

Gar ensemble

(1981, included in "Offering Clouds: Music and Dance")

Tashi Tsering playing the Genka

(1981, included in "Offering Clouds: Music and Dance")

However, after reviving Gar and securing its place as a national-level intangible cultural heritage, the focus of many artists shifted toward preserving Gar dance and vocal traditions. Meanwhile, the Genka gradually faded into the background, confined to archives and museum display cases. After becoming an intangible cultural heritage inheritor for both Gar and Dranyen arts, Tashi Tsering remained busy with passing on these traditions. Within major professional art groups in Tibet, artists capable of fully mastering the Genka became increasingly rare, pushing Genka art once again to a crossroads of inheritance.

Tashi Tsering and younger-generation inheritors

(2018)

Since 2010, after systematically organizing Dranyen, Toeshey Nangma, and Gar, Tashi Tsering passed the responsibility of their inheritance to the next generation of artists and professional organizations. He then shifted his focus to researching Genka art. In 2023, Tashi Tsering and his student Lhob (stage name "Galawangbu") began reviving Genka art.

Tashi Tsering and Galawangbu

(2023, photographed by the author)

Tashi Tsering and Galawangbu began by systematically organizing the Genka's tuning system, which had been established in the 1980s, and then proceeded to study its playing techniques. They also contacted specialized factories to explore mass production of the Genka. As a Dranyen artist, Galawangbu teaches Gar art to younger generations in his own studio, using this as a way to support the revival of Genka. Simultaneously, Tashi Tsering and Galawangbu are preparing to report and seek approval from higher authorities in hopes of having the art of playing the Genka included in China's "Intangible Cultural Heritage List."

Galawangbu playing the Genka

(2024, source: Galawangbu)

At the 2024 Tibetan New Year Gala, Galawangbu and his students officially performed this precious song and dance art on stage, during which they formally played the Genka. This marked the first time this instrument, lost for nearly forty years, had been presented on a public stage.