From Rock Star to Zen Poet ▎Leonard Cohen

"The Autobiography of Leonard Cohen"

The old man is kind, the young man is angry,

Love may be blind, but desire is not.

-- "The Sorrow of the Old Man"

You go your way,

I'll go your way too.

-- "The Sweetest Short Song"

Why should I tremble on the altar of enlightenment?

Why must I wear a smile forever?

-- "The Collapse of Zen"

Book of Longing

In 2006, Cohen published the poetry and art collection "Book of Longing." The poems in this book were written at the Mount Baldy Zen Center, Los Angeles, Montreal, and Mumbai, and it also includes nearly a hundred of his drawings, large and small, interspersed among the poems. The playful and provocative nature of the artwork complements the meditative, open-ended, and subtly darkly humorous poetry, creating a harmonious and well-matched collection. It is a remarkable book that can be quietly recited or sung softly while also offering a visual feast.

This brilliant and moving collection reflects the transformation in Cohen's inner world. During those years, his melancholy found full release, and Cohen attributed this book to his experiences with Zen meditation.

"Book of Longing"

In the preface to the book, translator Kong Yalei wrote: "All religions exist for the same purpose—to resolve the suffering of being human. Zen is no exception. And human suffering primarily stems from two aspects: the spiritual and the material, or more specifically, the self and desire.

But what sets Zen apart from all other religions is its unique approach—it advocates facing rather than escaping; it advocates intoxication rather than endurance; it advocates decisive action rather than contemplation; it advocates immersion in the present rather than hope for the afterlife; it advocates relying on oneself rather than praying to deities."

After reading *Book of Longing*, I believe the revelation it brings us is this: when we truly learn to face the self and desire, and achieve inner harmony and self-reconciliation, we, like Cohen, can embark on a new chapter of life under the strategic guidance of Zen.

"Book of Longing" interior page, photo by the author.

Leonard Cohen

In 1934, Cohen was born into a Jewish middle-class family in Montreal, Canada, where Yiddish was spoken at home. However, Montreal is located in Quebec, a French-speaking and predominantly Catholic province (which is why his lyrics were often re-sung in French later in his career), and the nanny who raised him was an Irish Catholic immigrant. Cohen received an English-language education and attended McGill University, where instruction was in English. With such a diverse cultural background, it is no wonder that his first poetry collection, published in 1956, bore the peculiar title *Let Us Compare Mythologies*.

Cover of "Let Us Compare Mythologies"

At the age of nine, Cohen’s father passed away, and he watched as his father was buried in the earth. His mother was a Russian refugee whose homeland had been destroyed by war. The loss of his father and his mother’s experiences had a profound impact on Cohen. He suffered from depression for decades, which helped shape the distinctive style of his later work.

Cohen was an exceptionally accomplished poet and novelist, but he is most widely celebrated as a rock superstar. I believe that among rock music enthusiasts, no one is unfamiliar with his name. In this article, however, I will focus solely on how he developed an interest in Zen Buddhism and how Zen influenced his subsequent creative career.

During the 1970s and 1980s, propelled by the "New Age" movement, a Tibetan Studies school emerged and grew within the United States. The founders of this Tibetan Studies school were Jeffrey Hopkins (born 1940) from the University of Virginia and Robert Thurman (born 1941), the "Tsongkhapa Chair Professor" of Indo-Tibetan Studies at Columbia University. They were quintessential representatives of "The Beat Generation."

This generation rejected orthodox Western values, instead seeking spiritual liberation from Eastern religions. They vehemently criticized materialism, experimented with psychedelic drugs, and practiced sexual liberation in order to personally experience the extremes of human existence.

Robert Thurman

If Hopkins and Thurman studied Buddhism to seek their own spiritual liberation, then I believe Cohen turned to the practice of Zen within Eastern religions to free himself from the struggles of depression. This aligns closely with the intellectual and experiential journeys of Hopkins and Thurman.

The Silent One

In 1973, at the age of 39 and not long after his singing career began, Cohen met his lifelong spiritual mentor, Japanese Rinzai Zen master Kyozan Joshu Sasaki. From then on, Cohen began to engage with Zen Buddhism, maintaining a consistent practice over the years. Reportedly, he would even sit in meditation cross-legged during flights.

After nearly two decades of guidance under Kyozan, in 1992 at the age of 58, Cohen decided to enter a Zen monastery. His place of practice was the Rinzai Zen "Mount Baldy Zen Center," located in the San Bernardino Mountains on the outskirts of Los Angeles. For the first few years, Cohen participated in monastic life as a lay practitioner. Four years later, in August 1996, he officially took monastic vows, shaved his head, and became a monk. Sasaki gave him the dharma name "Jikan," meaning "The Silent One"—a fitting name indeed for a singer. Having devoted most of his life to Zen and taking monastic vows at the age of sixty, Cohen’s earnestness in both character and actions is unmistakable.

Irwin Allen Ginsberg, a fellow Jewish poet who converted to Buddhism, once asked him if he had abandoned Judaism as a result. Cohen replied, "I didn't come to the monastery to seek religious faith. I am quite content with my old beliefs. I simply felt that my life was disordered, chaotic, gloomy, and painful. I didn’t know where these feelings came from. In the Zen school I practice, there is no worship, no deities, so logically, there is no conflict with Judaism." Perhaps it was precisely the liberating doctrine of Rinzai Zen—"no Buddha to seek, no path to attain, no dharma to obtain"—that gave Cohen the space to avoid religious dogma.

During Cohen's Zen Practice

Voiceover for "The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying"

In 1999, after leaving monastic life, Cohen traveled to Mumbai, where he met the philosophy master Ramesh S. Balsekar (1917–2009), a disciple of the Indian sage Sri Nisargadatta Maharaj. Balsekar advocated the philosophical concept of "non-dualism." Cohen spent a year studying under his guidance.

Cohen and Indian teacher Ramesh Balsekar

Cohen recalled, "Traditional therapy encourages patients to embrace their inner feelings—as if there is an inner self, something we are always searching for—the authentic self. In reality, there is no 'fixed self' commanding you to be loyal or dictatorial. There’s no need to seek answers to questions, because the questions themselves vanish. As one of Balsekar’s students put it: 'I believe in cause and effect, but I don’t know where cause and effect come from. Every effect generates a new cause.'"

Through this daily process of learning and realization, Cohen’s depression gradually lessened without him even noticing it. He was particularly fond of a quote by playwright Tennessee Williams: "Life is a fairly well-written play… When the curtain falls, no one can predict what will happen, but I only know that life is worth living."

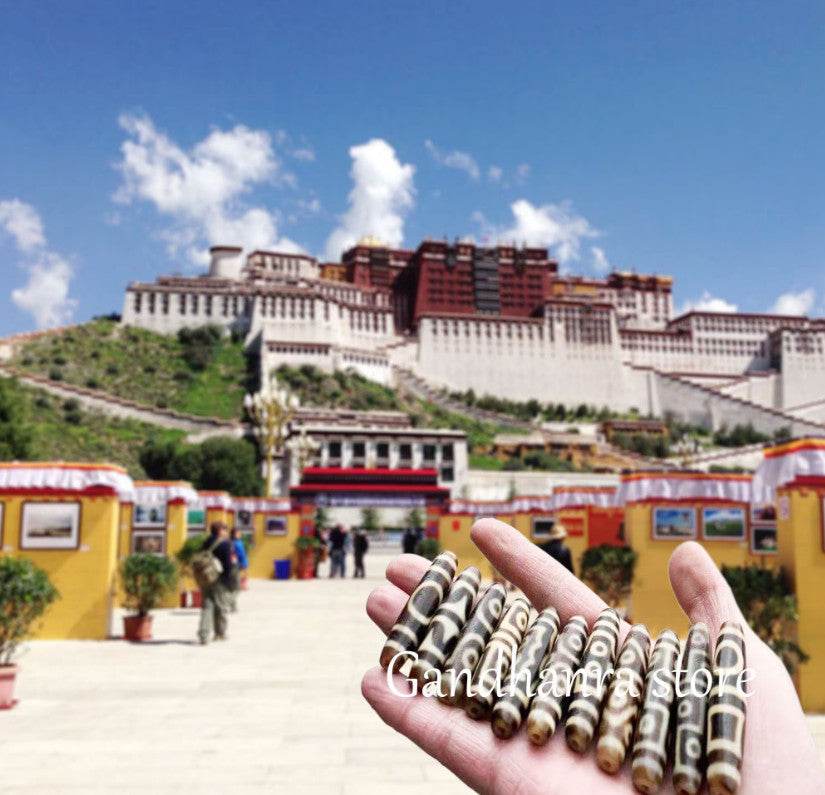

As Williams said, life is a play, and sometimes fate is wonderfully mysterious. Speaking of which, Cohen also had an indirect connection with Tibet during his Zen practice. In the 1990s—I believe around the time Cohen entered the monastery—NHK and a Canadian company produced a two-part video series on *The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying*, for which Cohen provided the voiceover narration. This little episode truly surprised me.

The Tibetan Book of Living and Dying

"Letter to Chinese Readers"

Cohen published his novel *Beautiful Losers* in 1966. When the Chinese translation was being prepared in 2000 (published by Yilin Press in 2003), he specifically wrote a "Letter to Chinese Readers."

In the letter, he wrote: "When I was young, my friends and I admired the ancient poets of China and loved reading their works. Our ideas about love and friendship, drinking and parting, and even poetry itself were deeply influenced by those ancient verses. Years later, I embraced Buddhism, became a disciple of Master Kyozan, practiced Zen under his guidance, and diligently studied the inspiring scriptures of the Rinzai school every day.

Dear readers, you can thus understand my feeling of gratitude—shallow as I am, I have had the fortune to dwell, even if only briefly, on the edges of your rich traditional soil and benefit from it." From this, I venture to speculate that Cohen’s connection with Eastern religions may have been destined even in his youth.

"Beautiful Losers" Cover, Photo by the Author

As a postmodern metafiction (where "metafiction" refers to fiction about fiction), *Beautiful Losers* is deeply rooted in the social and political realities of North America in the 1960s. It serves as a vivid portrayal of that turbulent history and unrestrained lifestyle. With the distinctive character of early postmodern works, it also heralds the rise of postmodernist novels in the 1970s and 1980s. Among all Western rock superstars of that era, only Cohen truly achieved a perfect integration of literary art and Zen spirit, marking a unique creation of his own.

Waiting for the Miracle

From Cohen's entry into the Zen monastery in 1992 to his return to secular life in 1999, the years he spent practicing Zen seemed almost isolated from the world, with no new songs released. It wasn’t until February 2, 2000, with the release of "Waiting for the Miracle," that he broke this silence. In my view, this song is undoubtedly a milestone work in Cohen's career.

“Waiting for the Miracle” Cover

This is also my favorite work by Cohen and served as my initiation into enhancing my appreciation of music, especially rock. The lyrics and arrangement are filled with an illusory, ethereal, dream-like quality. With his deep, restrained, and magnetic voice, Cohen delivers this over-seven-minute masterpiece in a "Blues-style melancholic and sentimental" manner.

I know you really loved me

But,you see,my hands were tied

I know it must have hurt you

It must have hurt your pride

When you know that you've been taken

Nothing left to do

When you're begging for a crumb

Nothing left to do

When you've got to go on waiting

Waiting for the miracle to come

The pain brought by love always carries a strong sense of beauty. Cohen seamlessly incorporates Zen-like language and Zen spirit into the lyrics of this song—an achievement in which no one can rival him. His pessimism and the paradoxes of love, the paradoxical tension underlying his everyday language—this is precisely the most captivating aspect of Cohen's lyrical art and the greatest gift Zen has given him.

The everyday language in Cohen's lyrics is the most fitting language of Zen—a form of expression deeper than complex and intricate poetry. However, everyday language is not necessarily poetic language; poetry lies in the paradoxical tension hidden behind the simplicity. The straightforward and easily understandable nature of everyday language happens to suit singing, perhaps by chance. Did Cohen turn to Zen because his lyrical style required it, or did he develop this enchanting style because he embraced Zen? Analyzing Cohen's lifelong creative journey carefully, it seems both are true.

Breaking the Attachment to Songs

In the eyes of Westerners, Buddhism is often seen as a "religion of sorrow." After attaining enlightenment, the Buddha taught the "Four Noble Truths," the first of which is the Truth of Suffering: life is filled with suffering, and the "Eight Sufferings" serve as the foundation of Buddhist philosophy.

After embracing Buddhism, Cohen came to understand sorrow as a natural state of human existence, which in turn granted him a sense of inner peace. Therefore, whether Cohen was a devout Buddhist, in my opinion, is not the most important question. He may have simply sought mental tranquility through Zen, but at the very least, Zen provided him with an aesthetic that resonated with his spirit—the "everyday language" aesthetic of "sweeping away literary obstacles and pointing directly to the mind." This endowed him with a unique style for songwriting and poetry, as well as a distinctive way of viewing the world, allowing him to stand out among countless rock musicians.

Cohen as a Monk

As a Zen-inspired singer, Cohen did not cling to the consistent artistry of lyrics. His best way to break the attachment to songs was to write songs that did not resemble songs. This reflects the steep and uncompromising style of the Rinzai Zen school, which emphasizes "breaking all attachments" and "attaining freedom through radical liberation." Cohen approached his lyrics with extraordinary seriousness and invested immense time in their creation, much like the renowned song *In My Secret Life*, whose lyrics underwent countless revisions over more than a decade.

I smile when I’m angry

I cheat and I lie

I do what I have to do

To get by

But I know what is wrong

And I know what is right

And I’d die for the truth

In my secret life

Do you find such lyrics particularly special and literary? They seem to be just plain language, something even a middle school student could translate better than a graduate student like me. Yet, it is precisely these repeatedly revised plain words that carry a sense of Zen-like casualness and approachability. Lyrics like these are destined to stand the test of time.

In My Secret Life Album Cover

Leonard Cohen

September 21, 1934 - November 7, 2016

Canadian poet, singer-songwriter, novelist, painter, and Zen monk. He rose to fame in the literary world early in his career with his poetry and novels. His work consistently explores themes of religion, solitude, sexuality, and power. He was inducted into the Canadian Music Hall of Fame, the Songwriters Hall of Fame, and received Canada's highest civilian honors, including the Order of Canada and the National Order of Quebec. He was also elected to the American Rock and Roll Hall of Fame and received a Grammy Lifetime Achievement Award at the 52nd Grammy Awards.

1 kommentar

2rd24p