Returning to Tibet twenty years ago.

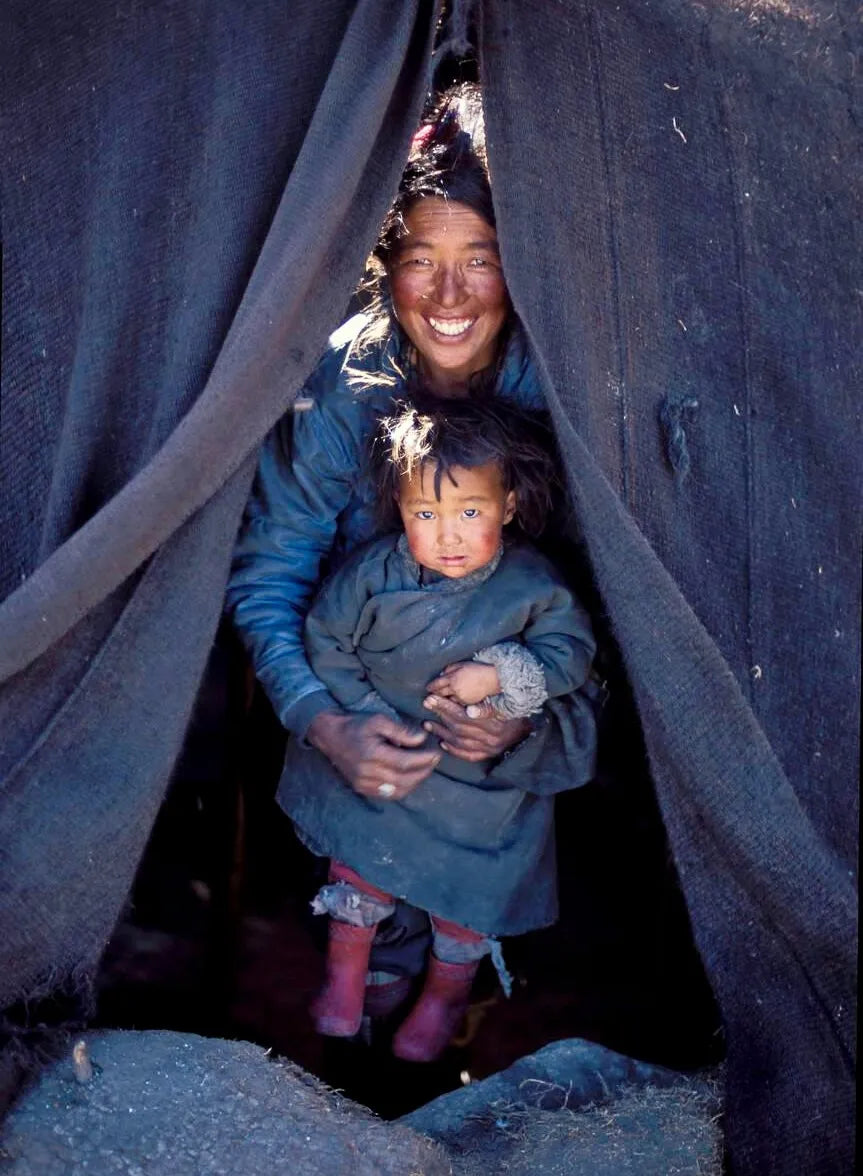

A Drokpa mother and her child

Photography: Christophe Boisvieux

Tibetan folk music

In the late 1990s, the renowned British independent music label Saydisc recorded a collection of folk music from regions such as Lhasa, Sertar, Shigatse, and Nagqu in Tibet, and officially released it to the world in 1999.

Lhaze Boy

Upon its release, this precious album "Tibetan Folk Music" immediately attracted the attention of numerous music critics and global music enthusiasts, who strongly recommended it. They unanimously agreed that the album possesses extraordinary value across multiple domains such as aesthetics, academia, and art, and its release would strongly appeal to scholars, music creators, and those with an exploratory spirit and passion for world music from around the globe. And indeed, it proved to be so.

Album cover

The Saydisc official website recommends this album as follows: "This album focuses on Tibetan secular music, showcasing the authentic sounds and life atmosphere of the high plateau. Unlike previous Tibetan music works that predominantly feature religious chants, this album includes urban folk songs from the Lhasa region, traditional ballads of nomadic peoples, and various instrumental performances with distinct regional characteristics."

"It is a sonic journey from the 'Roof of the World,' guiding listeners into a vibrant, rustic, and rhythmically rich Tibetan musical world—where melodies passed down through markets and tents amidst vast grasslands, snow-capped mountains, and lakes await to be heard and cherished."

1995, Tibetan folk singer

Photography: Tom Mueller

Sonic cultural heritage

For a considerable period, the Tibetan music accessible to Western societies was almost exclusively religious music, and people's understanding and impression of Tibetan music largely remained confined to this aspect. In contrast, music directly reflecting the secular lives and emotions of the people from folk traditions was extremely rare.

While it is understood that Tibetan culture is centered around religion, and religious music, as a vital component of ritual practices, contains unique and profound depths, it is nevertheless regrettable that such music presents barriers for appreciators outside the native culture. This is because religious music does not serve simple emotional transmission on a secular level; instead, with its low, resonant tones, trained recitation techniques, and unique melodies, it aims to facilitate spiritual purification and elevation. Without a certain degree of familiarity with the religion and some knowledge of its scriptures, it is nearly impossible to grasp even a fraction of its charm.

Jampaling Monastery, tourists experience playing traditional religious instruments

Photography: Norma Joseph

Entering the new century, as an increasing number of Tibetan cultural elements gradually integrate into the global cultural context, Saydisc's release of this music album is particularly timely. In fact, since the mid-1960s, Saydisc has actively positioned itself at the forefront of recording and preserving extraordinary, unique, and historically rich folk traditional music from around the world, dedicating itself to safeguarding these precious sonic cultural heritage for future generations.

Label logo

Thanks to its consistent innovation, professional dedication, and exceptional quality over the years, Saydisc has earned a global reputation across decades. Its music releases encompass world ethnic music, traditional and regional folk songs, as well as performances on distinctive musical instruments. For the purposes of music documentation and cultural preservation, most of Saydisc’s music is currently sold at affordable prices, with select full albums or curated tracks available for online streaming or download via the official website.

2002, Garzê, a man playing and singing

Photograph by Leisa Tyler

Folk music is primarily characterized by its authentic emotions and straightforward expression, making it the most likely to resonate instantly with listeners. This precious spontaneity and raw quality imbue folk songs with enduring vitality, ensuring they never feel outdated no matter when or where they are heard—instead, they often become even more timeless and refreshing with age.

These songs need not come from trained professional artists well-versed in technical skills. On the contrary, while traveling through Tibetan regions, one might encounter a passerby who can spontaneously break into song. With their unique vocal qualities and rhythms, the singers vividly express their innermost feelings in the moment, often infused with a simple yet profound understanding of life, existence, and nature.

2002, Garzê, a man performing and singing

Photograph by Leisa Tyler

Art that does not emphasize technical skill

Like most anthropological field recordings, the beauty of this music—untouched by high-tech enhancements—relies almost entirely on the spontaneous, naturally pure yet skilful singing style of folk performers. Whether joyful, sweet, solemn, or resounding, the tones and melodies instantly transport listeners, immersing them in the emotional world of the singers.

The lyrics of many Tibetan folk songs are remarkably simple, free of complex rhetoric, and sometimes consist of just a few lines repeated with varying melodies. Their meaning is as direct and unmistakable as an open door. Emotions flow naturally through the voice without abstract transformation—a genuine and heartfelt expression.

Man Spinning Thread

In the Tibetan worldview, many aspects and details of ordinary daily life are worthy of being celebrated in song, and all genuine emotions arise from heartfelt inspiration. Upon careful reflection, these lyrics invariably point to existence, emotion, fate, and time itself. Yet the singers make no effort to explain, nor are they adept at explanation—instead, they invite listeners to feel and interpret through rhythm. At times, the simple yet moving singing can even evoke a profound appreciation for the beauty of emptiness.

Tibetan folk songs can be described as a form of wisdom that does not pride itself on knowledge, and an art that does not emphasize technical skill. The singing bears no trace of artificial polish—it flows naturally from the very essence of existence, like a mountain spring bubbling forth or a breeze brushing against the face. Listeners feel no sense of distance; even without understanding a word of Tibetan, one can fully appreciate its beauty.

Ngari Shepherdess

In Tibet, people do not analyze love through theories, nor do they employ complex concepts to discuss profound questions of life and death. Perhaps it is precisely because they live in a place so close to nature and spirituality that worldly existence does not require a complex external theoretical system to understand and interpret the world. On the contrary, it is through the authentic presence of each moment that life is expressed in its most profound and moving way. Elsewhere, philosophy is an academic discipline, a subject of thought—but in Tibet, the philosophy of life might simply be a humble song.

Tingri Women Having Morning Tea

Singing as an Offering

Facing the sun, moon, mountains, and rivers with deep reverence; feeling gratitude and compassion toward revered elders; witnessing a field of thriving, vibrant crops; gazing at clouds lingering over mountain ridges; watching a bright full moon rise over the eastern hills; experiencing a brief but beautiful encounter with a maiden—in all these moments, a song arises spontaneously from the heart. Every emotion finds expression through song. This beautiful tradition of offering songs as tribute and conveying feelings through melody has a long history in Tibet. It is not about pleasing listeners or gaining applause, nor is it about performance or satisfying personal vanity. Rather, such singing stems from sincere devotion and the spirit of offering.

Gyatso La Pass

Offering should not be narrowly interpreted as religious rituals or material gifts. Its true meaning extends far beyond. A beautiful voice, a sincere heart, and even every act filled with goodwill and reverence can be a precious offering—a tribute and homage to all that is beautiful and divine.

An artisan painting a thangka with focused dedication in the stillness of night is an offering;

A herder leading sheep out at dawn, turning a prayer wheel while softly chanting the six-syllable mantra, is an offering;

A woman who loves beauty, placing a pot of blooming flowers on her sunlit balcony upon waking, is an offering;

An elder carefully brewing a pot of rich butter tea is also an offering.

Offering is not confined to a specific form—it resides in the clarity and purity of the heart, and in the compassion and reverence held for all things.

Gyatso La Pass, woman beside a tent

Especially as singing is the most direct expression of human thought, a heartfelt and sincere song is like a flower blooming fully in the present moment. To witness it is to encounter something sacred in a once-in-a-lifetime moment. This unique practice of offering through song does not belong to the realm of form or entertainment—it simply signifies a way of being human. It is a poetic and moving response to all things. The moment of singing is the moment of connecting with the divine.

Gyangtse, Stupa and Prayer Flags

To engage with the world not merely as an unaware passerby, but to humbly integrate oneself into the rhythm of the universe. Winding rivers hold spiritual energy, towering mountains emanate divinity, the wind breathes, and the earth pulses. Faced with all this, one cannot help but offer a song brimming with emotional depth, expressing reverence for the wonder of existence.

Saga Grassland

Where words cannot reach, people convey through song. It might even be said that words are often limited, while singing always serves as a perfect vessel for the spirit—transcending language and text to convey the mysteries of life.

Viewing Mount Cho Oyu from the village

The Sound of Existence

Among all folk songs, those related to labor are particularly cherished. The tradition of improvising songs during work represents a continuation of oral culture—never recorded in writing nor preserved in musical scores. It does not belong to the realm of monumental, tangible cultural heritage but sustains a community’s understanding and expression of nature and life through daily repeated actions and spontaneous singing.

Each generation seems naturally born with the habit of using songs to converse with the sky, the earth, the grasslands, and their livestock. People on the plateau understand how to treat every fruit of their earnest labor with tenderness and respect. While shearing wool, they sing in gratitude to their animals; while collecting and transporting salt, they respond with songs to the earth’s generosity. Circumambulating mountains, carrying water, sowing seeds, building homes—within these everyday labors lies an ineffable beauty, deeply felt but difficult to articulate in words.

A shepherdess holding a goat

Perhaps this is why Tibetan folk music feels so textured and penetrating. These sounds do not emerge from stages—they are born spontaneously in countless vivid and specific moments and settings. The texture of life and the substance of existence are embedded in every melody. On the plateau, song has never been separated from life. Emotion and environment merge and intertwine; these are "sounds of living," "voices of existence."

Perhaps it is not only in Tibet. Wherever labor has not been entirely replaced by machines, and agrarian or pastoral traditions still endure, this practice of spontaneous, soul-deep singing—expressed through the instinct of the body—will not vanish. Just as, at times, looking back at fragments of the past preserved in visual records, one is instantly moved by the way people once engaged with life with passion and wholehearted presence. Beauty that touches the heart emerges quietly through slowness, focus, and sincerity.

Hoqu Herdsmen

Heaven, Earth, Human

The vast and sparsely populated natural environment of Tibet stretches the physical distance between people to seemingly infinite lengths. At times, driving hundreds of kilometers, one might encounter only a handful of herders scattered deep across the grasslands.

From the perspective of an urban traveler, these herders might appear lonely. Yet, with a shift in viewpoint and mindset, the seemingly small individual is, in fact, integrated into a boundless and expansive existence. A person stands between heaven and earth like a mountain—one individual representing all humanity in the philosophy of heaven, earth, and human. As an unparalleled experience of life, could there ever be a moment more joyful and fulfilling than this?

Mount Kailash and the Herder

When the wind sweeps across the grasslands and clouds hang low, the herder’s song rises in a seemingly boundless expanse of time and space—now faint and distant, now clear and soaring toward the heavens. It is sung for nature, and for existence. It is sung for the mountains, rivers, lakes, and seas; for the deities in the sky; and for the unseen hands of fate.

Tibetan folk songs are not mere embellishments added to life like decorative flowers on brocade—just as authentic life itself requires no redundant additions or elaborate rhetoric. Here, song has always been wisdom deeply rooted in lived experience, and it is precisely this that gives it the power to comfort the soul.

Drokpa Girl

Note: Except for a few images specifically credited to photographers, all other accompanying photos in this article are works by Christophe Boisvieux. Boisvieux began his career in media in the 1980s. In his spare time, he is also a traveler who has journeyed extensively around the world and published multiple travel photography collections. Asian countries with religious traditions hold a particular fascination for Boisvieux, and his photographic work primarily focuses on exploring "the relationship between humans and the divine." His representative works include *Lumières du Bouddha* (Lights of the Buddha).

This article is translated from Dalu's blog.

1 comentário

qqockk