Ink Culture of Tibet

"Copyist in Jyekundo"

Photograph by F. Maraini, 1937

National Museum of Oriental Art (Palazzo delle Esposizioni)

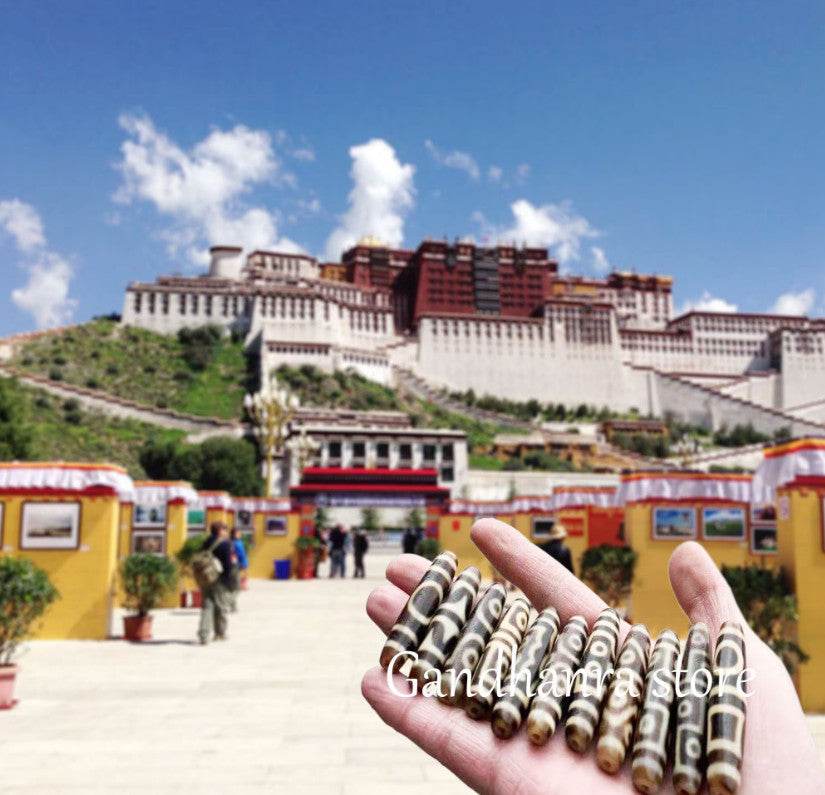

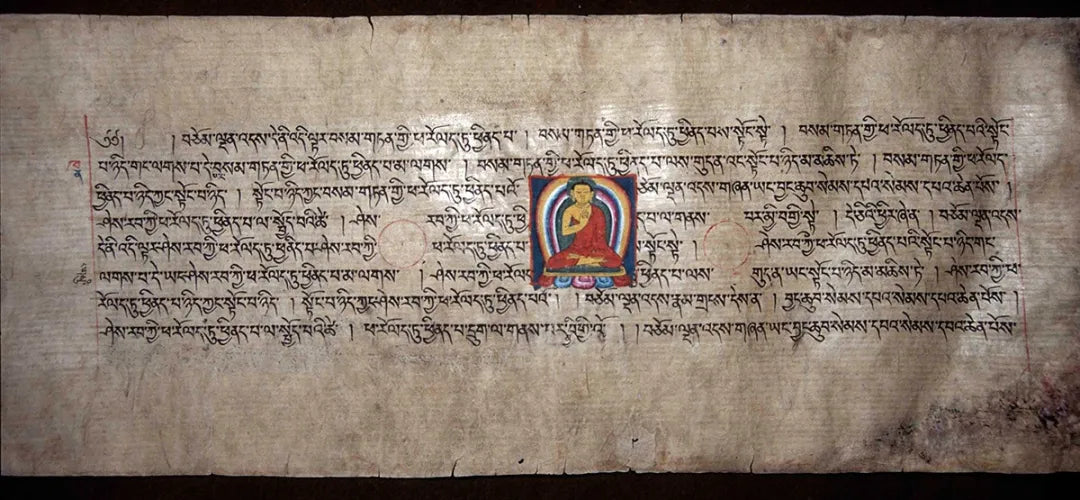

"Hand-copied edition of 'Twenty-Five Thousand Prajnaparamita Sutras', from the 13th to 14th century, at the Toling Monastery. 'Skillfully written in ink with colorful paintings of various deities.'"

རྩི་ཤིང་དང་ནགས་ཚལ་ལ་སྨྱུག་གུར་བྱས།

རྒྱ་མཚོ་ཆེན་པོ་སྣག་ཚར་བྱས།

ས་ཆེན་པོ་ལ་ཤོག་བུར་བྱས་ཤིང་།

བྲིས་ཀྱང་མི་ཟད་པ་ཡིན།

Turning trees and forests into pens

Turning the ocean into ink

Turning the earth into paper

Their writing knows no end.

In the collection of poems by the Great Master of the Direct Lineage, Jigten Sumgon,

there is a metaphor by Pakdzhepa Doje Jep:

"In distinguishing between the wise Banjhida and the virtuous yogi,

Banjhida is compared to a fruit-bearing tree,

While the virtuous yogi is likened to a jewel

embedded within a rock."

*Kagyu Lineage Masters*

13th century, Rubin Museum of Art

Detail: Phagmodrupa Dorje Gyalpo

*Tibetan Ink Bottle*

19th century, Songtsam Museum Collection

Ink containers (སྣག་བླུག་) and ink bottles (སྣག་ཀོང་/སྣག་བུམ་) have always been personal adornments for the literate.

"These ink tools are adorned with jewels and silks."

In the debate on "paper books vs. e-books", people often use the "charm of ink" to argue their points.

Everything is written on materials such as paper with ink. The unique smell of ink permeates the reading experience of the past.

In the classical period of Tibet, ink, pen, colored ink, and writing board were regarded as the "four treasures of the study".

In the Tibetan language, ink is generally referred to as སྣག་ཚ་ (snag tsha), which can be roughly understood as "dried black substance" (with controversy).

The two other related terms are སྨག་ (smag; dim) and ནག་ (nag; black). Ink is made by blending dry powder with water, like other writing tools in Tibet.

The history of ink is usually traced back to the time of Thumi Sangpo. When classifying the origin of ink, there are three categories: local style - Central Plains style - South Asian style.

Black ink traditions are associated with the Central Plains, while multi-colored ink is more associated with South Asia.

Ink is also classified into three categories based on its color and material: regular black ink (independent system) - gold and silver ink - multi-colored precious ink.

These classifications are also reflected in technical studies and are generally categorized under the field of "pigment studies". (For more information on "pigment studies", please refer to the series on color studies).

*Woodblocks at Dege Parkhang*

Photographed by the author, 2024

Ink for woodblock printing was graded into four tiers.

Premium ink in classical Tibet was priceless.

Rulers of regions with scripture-printing institutes

(e.g., the Kings/Tusi of Dege and Jonang)

invested heavily in powdered ink procurement.

Some were master ink artisans themselves,

like the 9th Jonang King, Tsewang Dondrup(ཚེ་དབང་དོན་གྲུབ་; 1642–1680).

*Manuscript of the Perfection of Wisdom in 8,000 Lines*

11th–12th century, Tholing Monastery

*Woodblock of the Seven Royal Treasures: Fine Horse Treasure*

19th century, Rubin Museum of Art

In traditional Tibetan cognition: "Good ink demands worthy wisdom."

Five common narratives about ink exist:

1."Ink holds an ocean of wisdom"

One must approach ink with reverence—

it may transcribe scriptures, decrees, or legends.

The wise perceive mind-nature in a drop of ink;

the ordinary grasp impermanence through inked words.

2."Fine ink’s fragrance enchants beings of the three realms"

Often likened to "the scent of wisdom/monastic virtue,"

its aroma soothes those afflicted by the three poisons.

3."Formless ink and formed ink"

Beyond known ingredients,

spirits craft ink from:

Raksha blood-ink, Naga treasure-ink, Dakini rainbow-ink

(especially in terma texts and biographies).

4."Vermilion ink reveals dharma"

Tibet classifies cinnabar liquid (ཐེའུ་སྣག་) and red seals (མཚལ་ཐམ་) as ink.

Vermilion highlights sacred texts;

red seals authenticate worldly laws.

5."Five colors manifest five wisdoms; seven hues reveal seven treasures"

Multicolored inks from jewels—

pearl-white, turquoise-green, coral-red—

evoke transcendent contexts in specific texts.

*Blue Beryl Medical Thangka: Herbal Remedies*

Early 20th century, Lhasa Men-Tsee-Khang

Detail: Pine resin (སྒྲོན་ཤིང་།) and Barberry bark (སྐྱེར་པ་)

"Blue Lapis Tibetan Medicine Thangka: Classification of Medicines"

In the first half of the 20th century, the Tibetan Medical Bureau in Lhasa

Local: Han Chinese Ink (རྒྱ་སྣག་; superior and inferior)

*Specially made fragrant ink blocks from Wutai Mountain

Good ink can transform - can be virtuous - can last long(འཕྲུལ་ལྡན་པ་/དགེ་ལེགས་པ་/རྟག་ཐུབ་པ་)

The method of making ink in different regions of Tibet varies slightly

Based on existing craftsmanship classics, it can be divided into four items

Way of selecting materials - Way of obtaining materials - Ink making formula - Method of ink testing

Use wood to extract oil, use minerals to extract ink, use qingke to extract black residue

(Spruce and oil pine are the most common raw materials for making ink)

All of these are ways of selecting materials (animal excrement is also used in lower-quality ink)

Scrape/fry/bake/soak/squeeze/grind until filter and dry

(Butter is essential in this process)

All of these are ways of obtaining materials (specific tools vary by region)

Add brown sugar/red latex/various medicines/various precious treasures to the ink

To maintain the durability of the ink and add color and fragrance

All of these are ink making formulas(སྣག་ཚའི་སྦྱོར་ཐབས་)

Finally, ask professionals skilled in calligraphy and ink to test the ink

If it is a guide to using ink for Tibetan woodblock printing

Consider ink stain removal and anti-mixing ink methods

If making seal ink, there are three methods

There are two common methods for making cinnabar ink/red ink

This is just the tip of the iceberg

It should be noted that ink from the Central Plains entered Tibet with the new trade routes

Many ink making and color mixing classics are said to originate from Tang/Kun/ Song Dongjing Bian Liang

"The Panchen Lama's Previous Life Series: Gu Yi Master, Kubala Tsering"

19th century, THND Museum collection

Detail: Monks copying scriptures with ink