A three-time World Press Photo award-winning photographer, living in the fate of the Himalayas, a French director.

Eric Valli, born in 1952 in Dijon, France, is a renowned photographer and film director. Originally an apprentice woodworker, he abandoned everything at the age of 18, traversed Afghanistan on horseback, and later settled in Kathmandu. He gained international acclaim for his collaborative works with "Le Figaro" and National Geographic, including the series "Honey Hunters" and "Hunters in the Dark," winning the World Press Photo Award (WPP) three times. In 1999, he directed the film "Himalaya," which received an Oscar nomination and won the César Award. In 2014, he published the photography collection "Natural Corners: Exploring the Lives of People on the Edge of the World," which unveils the stories behind over 100 of Eric Valli's photographic works.

I love living in the lives of others,

in destinies where I do not exist.

He rode a horse across Afghanistan at the age of 18 and arrived in the Himalayas at 20.

In 1952, Eric Valli was born in Dijon, France. At the age of 13, his parents gave him a Kodak camera as a Christmas gift. The unexpected present stirred something deep within his sensitive soul—overwhelmed with joy, he was moved to tears.

At 17, Valli embarked on his first journey, traveling to the Middle East—Lebanon, Libya, Turkey—where he witnessed new ways of life and new forms of existence. An unknown world unfolded before his eyes, filling him with exhilaration and a profound sense of life's wonder. By the age of 20, he had crossed the golden sands of the Namib Desert in Africa, traversed the turbulent regions of the Middle East and Afghanistan, and finally arrived in Nepal.

Upon arriving in Nepal, he fell deeply in love with the land of the Himalayas. He stayed there for 20 years and began his photographic journey, exploring those living on the edge of the world and using his lens to document their stories. He once said, “I am a storyteller. To tell a good story, it takes time and patience. I love living in the lives of others, in destinies where I do not exist. The people I photograph are all my teachers. I quietly step into their lives, humbly live within their fates, and bear witness for them through my records.”

Two honey-hunter brothers

in the Himalayan mountains

Becoming "the honey hunters on the sheer cliffs"

The first story he documented was "The Ancient Honey Hunters on Himalayan Cliffs." During the honey-gathering seasons of spring and autumn, honey hunters from the remote mountains of central Nepal would climb precarious rope ladders, risking their lives by dangling over sheer cliffs to collect honey and sustain their livelihoods. This series of photographs graced the cover of National Geographic in 1988 and won first prize in the World Press Photo contest.

"One day, I was stranded on a rain-soaked cliff when a local invited me to take shelter in his wooden hut. Inside, I discovered a hanging vine ladder. Pointing to the cliffs thousands of meters outside his hut, he shared the story of his late father—a cliff honey hunter. Over the next few years, I trekked across countless mountain trails of the Himalayas in search of surviving honey-hunting tribes. By chance, I eventually found the world's last remaining master of the ancient honey-hunting craft."

That revered elder had no time to waste on a foreigner like me. So I told him, "If you pass away, your honey-hunting craft will vanish from this world—unless you have an apprentice. And I am that apprentice." Then I became his disciple and spent two years learning on the cliffs of an isolated village." Valli immersed himself in the experience, feeling the sunlight and rain of the primal forest. He merged with nature and forgot the self that belonged to the fragmented modern civilized world.

The honey hunters cling to rope ladders dangling in mid-air.

Treading through snow in search of yak salt caravans.

At the age of 27, someone told Valli that every winter, herds of yaks cross from Tibet through the Himalayas to the foothills of Nepal in search of new salt and food. He wanted to follow the tracks of the yak salt caravans. In the Himalayan region, he searched repeatedly through the valleys and nearly died from typhoid fever. Exhausted both physically and mentally, and running short on funds, he had to interrupt the expedition. After recuperating for some time and raising more money, he once again embarked on the journey to find the yak salt caravans. This time, amid a massive snowstorm, he finally encountered the yak salt caravan in Tibet.

This scene seemed to recreate a description Valli had read at the age of 12 in a travel book by the French adventure writer André about trekking in the Himalayas: "Huge snowflakes fell, covering us as we moved slowly and the beasts breathing heavily. High above 5,000 meters in the Himalayas, we walked on ancient paths trodden by ancestors. Herds of yaks, like ink marks across the steep snow-white mountains—yaks, people, snow—all moved between heaven and earth. How awe-inspiring."

Valli spent most of his life on the road, fully committed to pursuing photography. He vividly recalls a time when he stayed at a friend’s house, where forty years’ worth of National Geographic magazines were neatly arranged on shelves in the basement. He immersed himself in studying these magazines, carefully observing and analyzing the images, trying to understand why certain photos were chosen, the narrative connections between them, the logic behind their sequence and layout, as well as the varying scales of the pictures. He questioned why a particular image moved him and what emotions the photographer had infused into it. Lost in his hunger to learn, he spent three days and three nights absorbed in this study without even realizing it.

As a photographer, one is inherently a witness to stories and a teller of legends. He said, "I never intended to describe a beautiful scene with words, because I believe photographs are the most compelling medium. They are perfectly suited to tell a story: with a beginning, an end, clues, protagonists, the strength of characters, the fragility of humanity, and the pursuit within the heart. This process is what fascinates me the most."

The Himalayas: choosing the most difficult path.

In 1983, while herding yaks in the Dolpo region, Valli met the tribal chief Thilen. Once, while watching Akira Kurosawa's "Seven Samurai" together, Thilen turned to him and said, "You should consider making a film about the Himalayas. I believe film holds more power than writing or photography!"

In 1999, after nine months of overcoming immense challenges, Valli successfully filmed "Himalaya," a globally acclaimed movie set in Tibet. The story follows a Tibetan village nestled in the vast Himalayan mountains, where generations have relied on salt trading due to insufficient grain production. The lead role was played by his old friend Thilen, and through this film, Valli told the story of Thilen's life. He created this movie to leave behind a historical record for these simple Tibetan people. He said, "Local culture is slowly melting away like winter snow. But if we join forces to make this film, future generations will be able to understand the lives their ancestors once lived."

Thilen and Valli

He remembers visiting a practitioner in the Dolpo region when he was at a crossroads in his life, seeking advice from this revered monk. The monk told him, "When you face a choice, if you are strong enough, choose the path filled with thorns. That way, you will uncover your greatest potential." These words became Valli's motto and were vividly reflected in the film "Himalaya."

We invented electric lights, yet forgot that the night holds a sky full of stars.

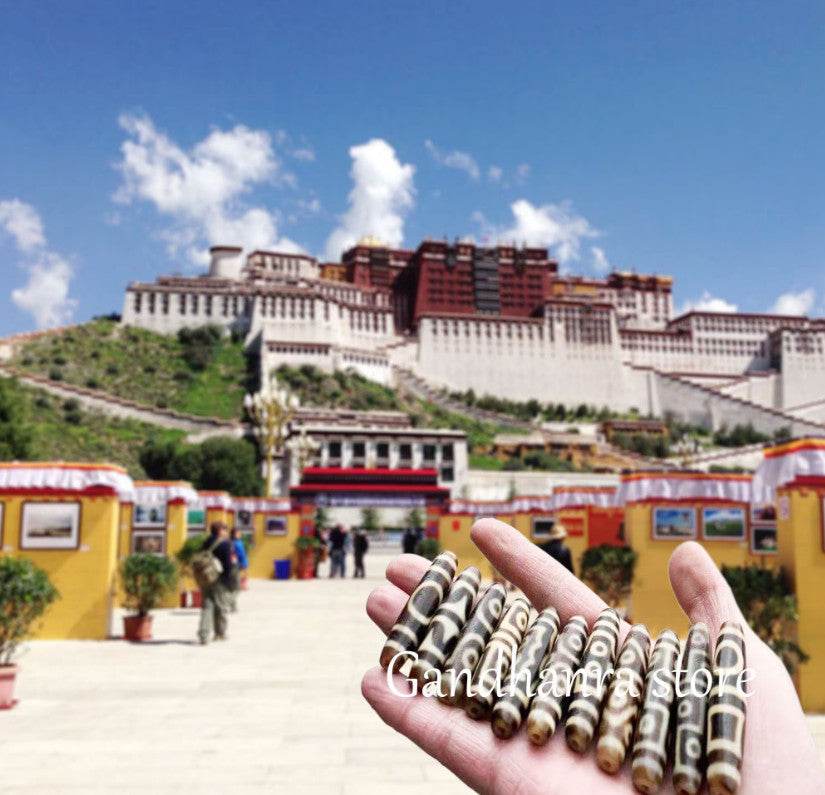

Later, Valli went to live at an altitude of 5,000 meters, digging for cordyceps alongside the Tibetan people. They shared life together for several months. Valli traveled back and forth across the perilous mountain peaks, captured a vast collection of photographs, and produced the documentary "Himalayan Gold Rush."

The cordyceps diggers

He admires those who are self-sufficient through manual labor—they know how to live. In contrast, we often forget that we are part of nature. We invented electric lights, yet forgot that the night holds a sky full of stars. We use efficient phones to save time, but don’t know how to spend it. The people of this highland possess an inherent resilience in their bones. Living for generations in the harsh plateau climate, the deep, ravine-like lines etched on their faces testify to their tenacious vitality.

During his 20 years in the Himalayas, Valli narrowly escaped death on multiple occasions. He survived avalanches, fell off cliffs, and faced numerous dangers. Compared to the length of life, he cared more about its breadth. He once said, "If you live fully, with vitality, then death holds no fear."

Valli spent his life narrating the destinies of others. Within these vivid stories lies his own shadow. Through frame after frame of moving imagery, he eternally captured these people forgotten by modern civilization—living silently yet powerfully in some corner of the vast earth, between heaven and earth. They have never been forgotten by nature.