Snake (སྦྲུལ་) and Tibetan Folklore

*"Collection of Common Tibetan Calendar Charts: The Sipaho Diagram"*

Mid-19th Century, Rubin Museum of Art

Detail: Alternating Dragon and Snake.

"Collection of Common Tibetan Calendar Charts: The Sipaho Diagram"

Late 19th Century, Rubin Museum of Art

Detail: Zodiac Snake Deity (ལོ་ལྷ་སྦྲུལ་).

ཨ་ཐང་ཐང་/ཨ་གར་ཐང་གི་ཐང་དཀྱིལ་ན།

མུ་ཏིག་ཤེལ་གྱི་ཕྲེང་བ་/ནོར་བུ་ཤེལ་གྱི་ཕྲེང་བ་ཞིག།

རིག་ནི་མང་ཡང་ལེན་ནི་དཀོན།

(Riddle)

In the fragrant grassland, in the agarwood field,

There lies a string of pearls and crystal, a treasure rare and concealed.

Many come to see, but few dare to take.

(Answer: Snake)

*"The Nanda and Upananda Story from the Jataka Tales Series: Group Nine"*

18th Century, Rubin Museum of Art, Designed by Situ Panchen Chökyi Jungné

Detail: Subduing the Naga King.

*"The Jataka Tales Series: Group Twenty"*

18th Century, Rubin Museum of Art, Designed by Situ Panchen Chökyi Jungné

Detail: The Severed Giant Serpent.

When it comes to snakes in Tibetan culture, people generally associate them with the following five aspects:

1. The "Lu (ཀླུ་)" in indigenous culture and Bön traditions,

2. The "Naga" derived from South Asian multicultural influences,

3. Buddhist scriptures and literary works featuring snakes that shape Tibetan narratives,

4. The iconographic system centered on snakes (such as the three poisonous snakes and snake ornaments),

5. The "snake metaphors" and "snake dream omens" in Tibetan medicine and astrology (with over thirty types of snake-related omens).

Similar to the translation debates surrounding "Khyung / Garuda / Great Golden-winged Bird", the terms "Lu / Naga / Dragon" also lead to various ambiguities due to translation. In the Buddhist context, "Naga" is associated with "serpent worship," alongside "seasonal narratives" and "treasure narratives." In Tibetan culture, the "Lu worship," often centered on snakes, does not stem from animal worship alone (fish, turtles, scorpions, etc., are also considered Lu).

As part of Tibetan cosmology, "Lu" represents the earth and water realms.

As part of Tibetan life studies, "Lu"symbolizes purity and healing.

As part of Tibetan epistemology, "Lu" signifies secrets and origins.

Using the snake as the primary subject for the artistic and theoretical representation of "Lu" is due to the biological characteristics and local symbolism of snakes.

*"Palden Lhamo the Remover of Obstacles"*

Mid-15th Century, Private Collection

Detail: Serpent Ornaments on the Yellow Mule.

*"Nagaraja Buddha"*

Late 12th Century, Mural from Garsha Monastery (དཀར་ཤ་)

Note the Naga ornamentation behind the figure.

Nagaraja Buddha is actually a past incarnation of Manjushri Bodhisattva,

and there is a specific sacred connection between Nagas and Manjushri Bodhisattva.

*"Blue Beryl Medical Thangka: Medical Ethics and the Explanatory Tantra"*

Early 20th Century, Men-Tsee-Khang, Lhasa

Detail: Using a snake's tongue as a metaphor for a physician's need to differentiate diagnoses when uncertain

(corresponding to the virtues of humility and caution in medical practice).

*"Blue Beryl Medical Thangka: Composite and Natural Poisons"*

Early 20th Century, Men-Tsee-Khang, Lhasa

Detail: During the churning of the ocean, the giant serpent spews venom, and Shiva drinks the poison.

Therefore, in Tibetan folklore and local legends, there exist independent narratives centered on snakes. Although these narratives intersect with the indigenous **Lu** and the South Asian **Naga/Dragon**, their core stories stem from the joys and sorrows of local life. After analyzing proverbs and tales about snakes from various Tibetan regions, I have tentatively categorized them into six types:

1. **Venomous Snakes**: Multi-headed snakes and green-spotted snakes are highly poisonous. Young farmers and herders must seek antidotes and healing lakes or ponds, such as the three-headed black snake (མགོ་གསུམ་སྦྲུལ་ནག་) in the Kongpo region.

2. **Deceptive Snakes**: Evil snakes disguise themselves as yak mucus to bite people, or use similar tricks like pretending to be a string of jewels. An example is the "Three Battles Between a Shepherd Boy and a Snake" in Nagqu's Biru County.

3. **Snake Ropes**: Ropes made from snakes can protect treasures, people, and livestock. Snake skins may also adorn rooftops, or snake bones may be strung into cattle or sheep ropes, as seen in the tale "The Merchant Borrows Snake Skin from a Giant Serpent" in Baiyu County, Kham.

4. **Snake Clans**: Snakes have family distinctions and conflicts among themselves. Snakes are used to symbolize regional histories and family disputes, such as the "Encounter Between the Southern and Northern Snakes" in Rutog County, Ngari.

5. **Disaster Snakes**: Giant snakes cause earthquakes and disasters when they move. Destroying snake nests brings misfortune, and slaughtering snakes brings plagues, as in the story "The Benevolent Mantrika Pleads with the Snake King" in Golok, Amdo.

6. **Benevolent Snakes**: Elderly snakes provide wisdom and answers when humans face confusion and hardship. Similar scenarios include snakes transforming into women to marry and assist ordinary men, as in the tale "The Young Monk Seeks Advice from an Elderly Snake" in Dege County, Kham.

It is important to note that this is a simplified classification system, not limited by regional culture, social class, gender, or time. The six narrative systems mentioned above may overlap in certain aspects.

*"King Gesar: Norbu Dradul / The Jewel that Repels Enemies"*

Late 19th Century, Private Collection, Woodblock Print

Detail: One of the Thirteen Werma, the Dark Venomous Snake.

*"Blue Beryl Medical Thangka: Classification of Medicines"*

Early 20th Century, Men-Tsee-Khang, Lhasa

Detail: Three types of animal treasures/stones related to snakes

(Blue-green, Yellow-green, Red-green).

Snakes have no wings, yet they coil across the earth, making the ground their sky.

Humans have no wings, yet with the four activities auspicious, their fortunes soar to the heavens.

(Selected from the oral teachings of Master Padampa Sangye.)

The tales of snakes in Tibetan culture are endless,

awaiting to be told again when the Tibetan New Year arrives.

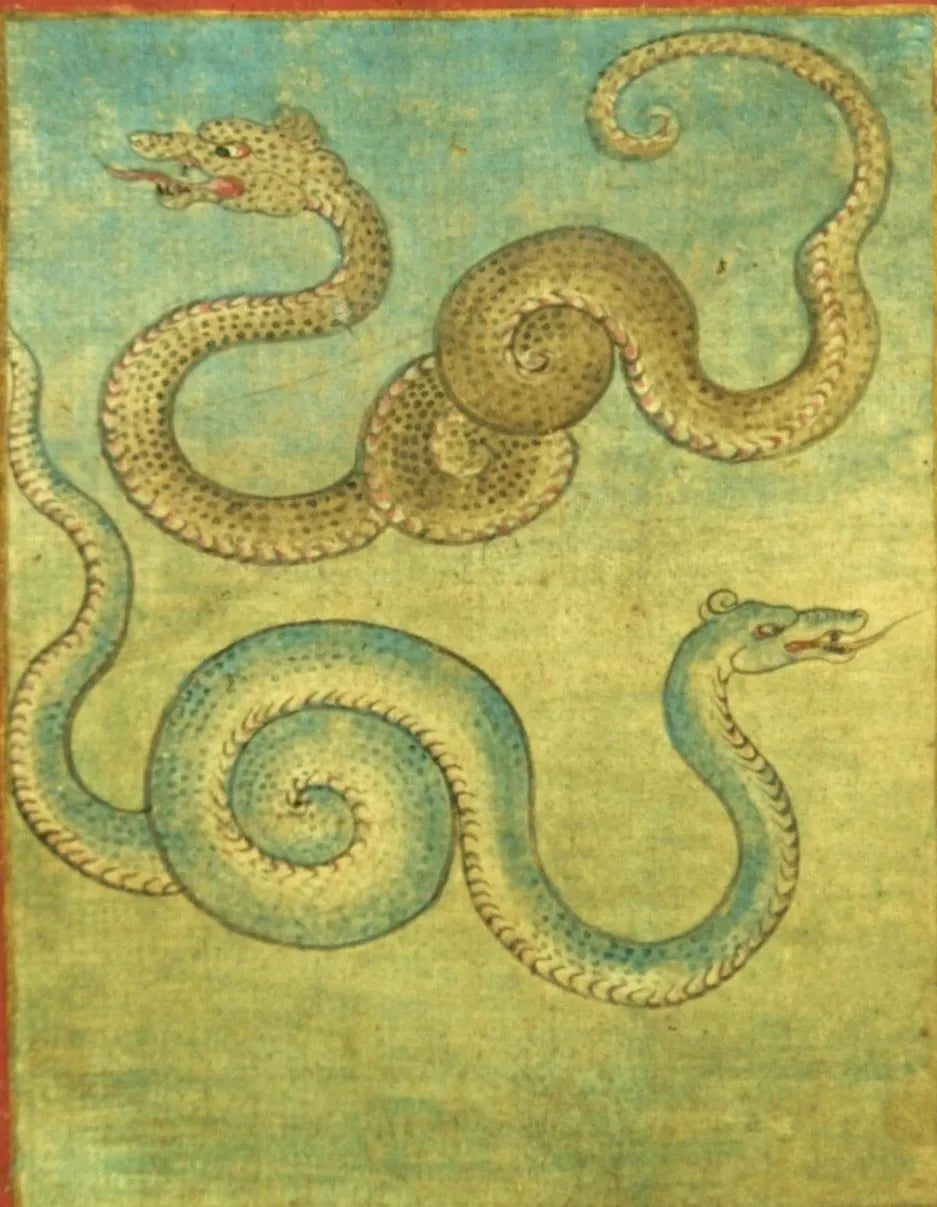

*"Animal-themed Tsakali: Male and Female Snakes"*

Late 19th Century, Private Collection.

This article is translated from Suolangwangqing's blog.

1 commentaire

8rq5vl