In the classical dance steps: Masks of the Himalayan region (Part 2)

"Yamantaka Ritual Dance Mask," 19th century, Zanabazar Museum of Fine Arts

"Gilded Openwork Ritual Dance Mask," 19th century, Rubin Museum

This mask represents the protector deity Mahakala.

Such masks typically appear in the ritual dances of major monastic temples

or in dances with special tantric lineages.

The funerary gold masks of Tibet belong to the category of shamanic masks.

"Yama Attendant Ritual Dance Mask," 19th century, Private Collection

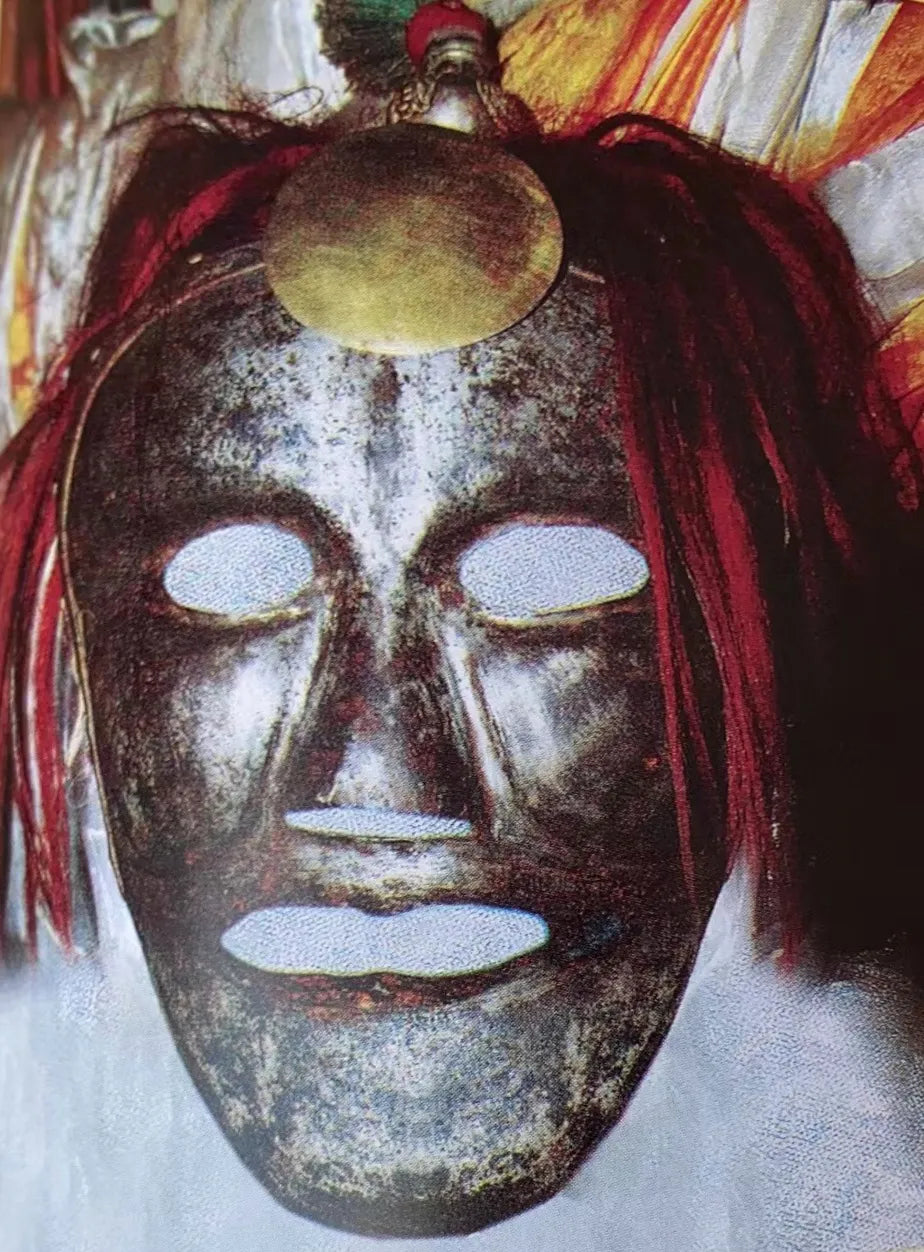

"Nepalese Tribal Village Mask," 18th century, Private Collection

With a deformed head and bared fangs,

one of the demons feared by the Gurung people in legend,

it uses illusions to lure people to their deaths.

The Origins of Classical and Village Masks

Around 2000 BCE, with the arrival of the Aryans, the living space of India's indigenous tribes was compressed. Modern people know very little about these外来 Aryans (Translator's note: Research on "Aryan migration" has established a relatively stable theoretical model). We only know that these groups, who entered the South Asian subcontinent through Afghanistan and the Hindu Kush mountains, spoke a Proto-Indo-European language.

The Aryans preserved an oral tradition concerning the Vedas (वेदः; meaning knowledge or wisdom), which forms the core textual system of Hinduism. Philosophically, they upheld the theory of causality and established the caste system along with "Brahmin supremacy" (i.e., the unity of priesthood and ritual) as social norms.

In summary, "pluralistic integration" is one of the defining features of Hinduism, which absorbed indigenous belief systems, such as the worship of "nature spirits." Numerous elements derived from animism were systematically organized and refined, gradually expanding the understanding of shamanic (or shamanistic) principles. This ultimately gave rise to a religion of "high culture" (i.e., Hinduism) that exhibits multi-layered indigenous characteristics.

It is worth noting that "Hindū," the root of the term "Hinduism," originally functioned as a geographical term rather than a religious identifier. Since the 18th century, Western societies have widely used the term to categorize all religions and cultures originating from India, while native scholars and politicians employed it to construct an independent ethnic-cultural genealogy.

"Elephant-Headed Lakshmi," 19th century, Private Collection

As one of the eight manifestations of Lakshmi,

it is associated with royal glory and worldly fortune.

In certain Hindu theatrical traditions,

elephant masks are linked to this deity

(or to Ganesha).

"Village Masks During Festival," Nepal, 1973

Another classical religion influencing Himalayan mask culture is Buddhism, which imposes stricter and more specific regulations on mask usage than Hinduism. The prince born in Kapilavastu over 2,500 years ago (Siddhartha Gautama) is now universally revered as the "Buddha," his life story widely known. To uncover the root of all suffering, the prince abandoned his opulent palace and retreated into the forest in pursuit of supreme enlightenment. After seven years (Translator’s note: the duration varies across accounts) of ascetic practice, he finally attained awakening under the Bodhi Tree in Bodh Gaya. Following initial hesitation, the Buddha resolved to share his hard-won wisdom with all sentient beings.

The Buddha’s teachings stem from a profound insight: despite humanity’s pursuit of happiness, suffering permeates existence. Yet, he did not stop there. Confronting anguish born of delusion, pride, envy, and other mental afflictions, one may transcend suffering entirely through disciplined ethical conduct and philosophical meditation, ultimately attaining non-dual insight into phenomena and truth. This transformative process is termed "enlightenment"—a state of profound freedom, clarity, and fulfillment.

Initially regarded as a quasi-"atheistic" philosophy, Buddhism later evolved an expansive pantheon due to humanity’s innate yearning for sacred personification.

"Shakyamuni Buddha," 11th century, Cleveland Museum of Art

"Bhutanese Tiger Face Village Mask," 18th century, Private Collection

"Güshi Khan's Battle Mask," traditionally dated to the 17th century, housed at Deqen Monastery, Jianzha County

The intersection of shamanic masks and village masks,

ultimately enveloped within Buddhism's historical context

(not classical masks).

The Spread of Buddhism

Since the Buddha first turned the Wheel of Dharma, Buddhism spread across most of Asia through both overland and maritime routes (ancient trade networks). The merchant class played a pivotal role in this diffusion, largely because Buddhism's path to liberation hinges on personal effort and promotes an independent, non-violent ethical code. Over centuries, Buddhism traveled northward through Central Asia and China, eventually reaching North Asia and Japan, while its southern transmission extended into Southeast Asia. The Buddhist traditions of Nepal and Tibet inherited the most philosophically intricate currents from South Asia, later permeating the broader North Asian region (including Mongolia and the Far East).

Buddhism is generally believed to have entered Tibet around the 7th century CE—marking the beginning of a fusion between indigenous beliefs and South Asian religions (Translator’s note: the exact timeline remains debated). At this fascinating historical juncture, Padmasambhava emerged as a central figure. Born in the Swat Valley (modern-day Pakistan), this master is said to have participated in the construction of Tibet’s first monastery, Samye (Translator’s note: this claim is contested). Legends recount how Padmasambhava subdued local deities and spirits, transforming them into guardians of the empire’s new faith. The narratives of "Padmasambhava and Samye" form the primordial backdrop for the origin myths of classical masks (and cham dances).

Buddhist teachings could be transmitted across all cultural strata through practices like ritual dance. As audiences immersed themselves in these dances, experiencing the sacred, Padmasambhava might appear in serene or worldly forms, while wrathful protectors like Mahakala repeatedly unveiled their ferocious visages. In parts of Nepal and Bhutan today (Translator’s note: particularly in Sherpa communities), this ritual dance festival is known as "Mani Rimdu" (མ་ཎི་རིལ་སྒྲུབ་), a 19-day ceremonial celebration.

"Guru Padmasambhava," 15th century, Newark Museum

The "subjugation of deities and spirits" is regarded as the meta-narrative of the Cham dance.

Meditating masked monks perpetually reenact this glorious moment,

a performance strictly adhering to ritual and scriptural prescriptions,

typically spanning three days.

"Guru Padmasambhava Mask," late 18th century, Mort Golub Collection

"Mountain Deity Protector Mask," 18th century, Mort Golub Collection

"Garuda Mask," 19th century, Mort Golub Collection

Tibetan Buddhism frequently employs imagery associated with death, which not only signifies the dissolution of self-awareness but also reflects the transient nature of physical existence. A quintessential example is the figure of the Charnel Ground Lord (Chitipati), a grinning skeletal deity from South Asian tradition, whose iconography and symbolism are deeply embedded in Tibetan practice. Notably, the Charnel Ground Lord also embodies Tibet’s "crazy wisdom" tradition. Typically appearing with dark humor and clownish antics, this deity provokes profound insights into mortality and liberation among spectators.

Such distinctive masks often feature in Tibetan opera (Lhamo), a genre blending dance and song to dramatize ethical narratives about overcoming negative forces through Dharma. Similar masks appear in the Deer Dance (ཤྭ་བའི་འཆམ་) performed by Bhutan’s Monpa and Sherpa communities. In this dance, a young hunter—already provisioned with enough food—succumbs to greed, only to be admonished by a deer, an incarnation of an ascetic, against exploiting nature beyond necessity. Through storytelling, the Deer Dance reinforces compassion (and ecological stewardship). Masks are reused across performances, as certain archetypal roles remain constant.

Earlier scholarly studies on Monpa and Sherpa masks (focusing on differentiation) relied structurally on Verrier Elwin’s (1902–1964) 1950s fieldwork. However, Thomas J. Pritzker’s (b. 1950) recent research has exposed flaws in this framework. This article moves beyond outdated ethnic distinctions, acknowledging stylistic variations rooted primarily in geography rather than presumed tribal differences. Strikingly, Monpa and Sherpa masks share remarkable similarities with certain Japanese masks—a convergence likely born from a shared Buddhist visual lexicon.

"Charnel Ground Lord Mask," 18th century, Mort Golub Collection

"Monpa-Sherpa Village Mask," 19th century, Mort Golub Collection

"Monpa-Sherpa Village Mask," 19th century, Mort Golub Collection

The study of Himalayan masks resists narrow categorization. When examining veiling practices in this region, we are inevitably drawn into an expanding discourse of geography and history. Through this lens, we glimpse a macrocosm spanning Eurasia and the Americas, bearing temporal imprints from the late Paleolithic era to the present. By contextualizing the discussion broadly and engaging deeply with masks, we come to appreciate the vast resonance of Himalayan mask culture—perceiving "this object" while tracing an artistic tradition that renews itself across ages.

Himalayan masks embody a truly international style, comparable to works as distant as those of Japan, Alaska, and Khotan (Translator's note: the cultural sphere of Central Asian oasis kingdoms). This globalized character is sustained by a cultural arrow piercing through time—launched from the shamanic traditions of the steppes and lodged finally in the classical rituals of Hinduism and Buddhism. The enduring, pollination-like dynamic between village masks and classical masks has revitalized both forms. As Carl Jung (1875–1961) observed of this phenomenon: the "deep psychological structure" of veiling remains unchanged; old gods return to the human world with new names.

"Monpa-Sherpa Village Mask," 18th century, Mort Golub Collection

"Monpa-Sherpa Village Mask," 15th century, Mort Golub Collection

"Smiling Beauty Mask," 1173, housed at Itsukushima Shrine, Hiroshima Prefecture, Japan

"Eskimo Mask," Eastern Hark Tribe, Southwest Alaska

Housed at the Peabody Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology, Harvard University

In my view, comparative analysis of numerous Asian masks reveals a striking unity of style and meaning—a unity that suggests a shared origin for masking traditions. In an era when most masks and their associated rituals are gradually disappearing, we can still attempt to piece together fragments of the past through surviving examples. While the Scythian "animal-style" (where animals embody power and authority) may belong to a specific time and place, Nepalese shamans, Tibetan monks, and Indigenous totem carvers of the Pacific Northwest have not rejected this artistic vision—rather, they have amplified it. Similarly, the Mahayana Buddhist ideal of bodhisattvas, symbolizing humanity’s yearning for wisdom and compassion, profoundly influences us all.

Madanjeet Singh (1924–2013) offered this reflection on masks in Himalayan Art (1968, first edition):

"These timeless images are undoubtedly the most wondrous and potent artistic bonds across the Himalayas. Masks confront us with something radically alien to our familiar cultures and aesthetics, yet perpetually stir us emotionally and intellectually. Their study offers an opportunity—to connect with our ancestors and gain sudden self-insight in the present moment."

Author: Thomas Murray