Brave the snowfield, the explorer lives forever!

When Westerners truly began to set foot in the snow-covered lands, a peculiar phenomenon emerged: their curses, malicious speculations, and bitter criticisms suddenly vanished without a trace. One after another, explorers traveling through Tibet marveled at the sacred purity of the snow-capped mountains, the serene tranquility of the lakes, and the peaceful contentment of the people. Those once-arrogant white men, who had looked down upon Tibet with disdain, overnight became its admirers, seekers, and dreamers...

The Forbidden Holy City

Entering the 19th century, Western explorers had far worse luck than their predecessors. During this period, Lhasa began closing its doors to outsiders, and hostility toward Westerners grew increasingly intense. Yet, this obstruction did not deter them—instead, it ignited an even more alluring and irresistible dream of the snow-covered lands in their hearts.

At the time, almost no Westerner could enter the Holy City. To those who had never set foot in Tibet, it remained the last untouched sanctuary on Earth. Western footprints had marked Africa, South America, and the Arctic—yet the Holy City alone, even when reached at its very gates, remained just beyond their grasp. They could only gaze longingly, unable to lift its veil of mystery or receive its sacred wisdom.

*Map of Lhasa*, drawn by Nikita Yakovlevich Bichurin, 1812

As Michèle Taylor observed:

For Westerners, the Tibetans' closed-door policy (which was also desired by the Qing court) only heightened its allure. This created a peculiar and arbitrary map, marked by concentric barriers of varying degrees. The closer one approached the Holy City, the more heavily guarded these barriers became: the outer borders, the inner boundaries of the central provinces, and the enigmatic snow-covered lands beyond.

In a rather farcical episode, in 1844, the French missionary Évariste Régis Huc (1813–1860) and his companion disguised themselves, darkening their skin and posing as itinerant monks on a journey from Gansu to the Holy City. While Huc smugly congratulated himself on his clever ruse, he remained unaware that his movements were under close surveillance by the authorities. Soon after, he was ordered to be expelled by Qishan, the then Imperial Resident in Tibet.

*Travels in Tartary and Tibet*, London, 1844 – featuring Évariste Huc and his assistant Father Joseph Gabet.

Huc was one of the few Westerners who managed to return alive from Tibet at the time. This was largely due to his identity—Tibetan authorities and locals had no reason to harm a missionary who posed no threat. After returning to China proper, Huc completed his travelogue, *Travels in Tartary and Tibet*. His multidisciplinary knowledge lent the work remarkable depth and breadth. Beyond its literary merits, the book fascinated readers with its eclectic and often whimsical observations. Most striking were his exaggerated depictions of Tibet, which both shocked and captivated Western audiences, igniting intense curiosity about the forbidden land.

Illustration from *Travels in Tartary and Tibet*, London, 1844

During the same period, the British clergyman Thomas Manning (1772–1840) also journeyed to Lhasa. Unfortunately, his Tibetan notes were at times overly brief, at others disjointed and trivial. Moreover, he seemed incapable of appreciating Tibet aesthetically, nor did he hold a favorable impression of Lhasa—possibly due to his unsatisfactory stay there. His accounts primarily highlighted the city's filth and poverty, and thus failed to make a significant impact in the Western world.

*Portrait of Thomas Manning*, RAS Head Catalogue 01.006, 1805

*Sketch of the 9th Dalai Lama by Thomas Manning*, RAS Head Catalogue TM/9/3, 1805

The Stage of British Explorers

In the 19th century, Britain was in the midst of its glorious Victorian era, and British explorers undoubtedly became the leading figures in the exploration of Tibet. During this period, British colonial expansion surged relentlessly. After fully annexing India, the East India Company turned its aggressive ambitions toward the Himalayan foothill states and Tibet. In 1888, using Sikkim as a base, Britain successfully invaded the snow-covered lands, marking the beginning of a new chapter in Tibetan exploration by British adventurers, officials, and missionaries.

Among them, the British missionary Annie Royle Taylor (1855–1922) stands out. In 1892, driven by devout faith, she embarked on her Tibetan expedition—frail in body but unshakable in spirit. Though barred from the Holy City, she gained worldwide fame as the first Western woman to enter Tibet. Adding to her legend, after completing her seven-month journey, Taylor chose to settle quietly in the Chumbi Valley, known as Tibet’s "southern gateway," where she ran a small shop for many years.

Miss Annie Taylor and Her Tibetan Attendants, unknown

*Passport Stamp of Annie Taylor at British Consulate in Fuzhou, China*, Warrington Archives Collection, unknown

Besides, a group of Britons including Arnold Henry Savage-Landor and Deasy also entered Tibet around this time. Little is known about H. Deasy’s birth and death years, except that he was a captain in the British XVIII Hussars. Judging from available photos, he appeared to be a young man during his time in Tibet. His travelogue *In the Forbidden Land* primarily focuses on describing his expeditions through the uninhabited regions of Tibet, with scarce accounts of entering populated areas—and even those are mentioned only briefly.

*Map of Wellby's Journey*, *Through Unknown Tibet*, 1898

Portrait of Wellby, Through Unknown Tibet

In his eyes, the people of Tibet were mostly filthy and unkempt. Upon entering a village, he described:

"It was the dirtiest and most dilapidated housing we had ever seen—and never wished to see again. The villagers were either blind, lame, or afflicted with various diseases, dressed in ragged and soiled clothes, idly basking in the sun on the mud-covered ground."

However, he held a favorable impression of merchant caravans and monks, likely because they had offered him assistance. He remarked that the caravan leader was "handsome, dignified, tall, and highly respected." A young monk at Kumbum Monastery impressed him as intelligent and erudite, effortlessly fluent in Chinese, Mongolian, and Tibetan, with broad knowledge that provided them valuable information.

*Illustrations from "Through Unknown Tibet" series*, 1898

The Swedish explorer Sven Anders Hedin (1865–1952), who served the British Indian authorities, was another prominent figure active in Central Asia and Tibet during this period. His work *Trans-Himalaya* meticulously documented his four expeditions into Tibet, causing a significant sensation. Unlike other Western explorers, Hedin described Tibetan nomads as mostly honest, kind, simple, and endearing. He also noted their philosophical acceptance of life and death, their peaceful mindset, and their carefree way of living. His accounts of Tibetan culture were relatively balanced and objective—a perspective likely shaped by his scholarly approach.

*Sven Hedin*, unknown

*Sven Hedin's Discoveries*, The Museum of Ethnography, unknown

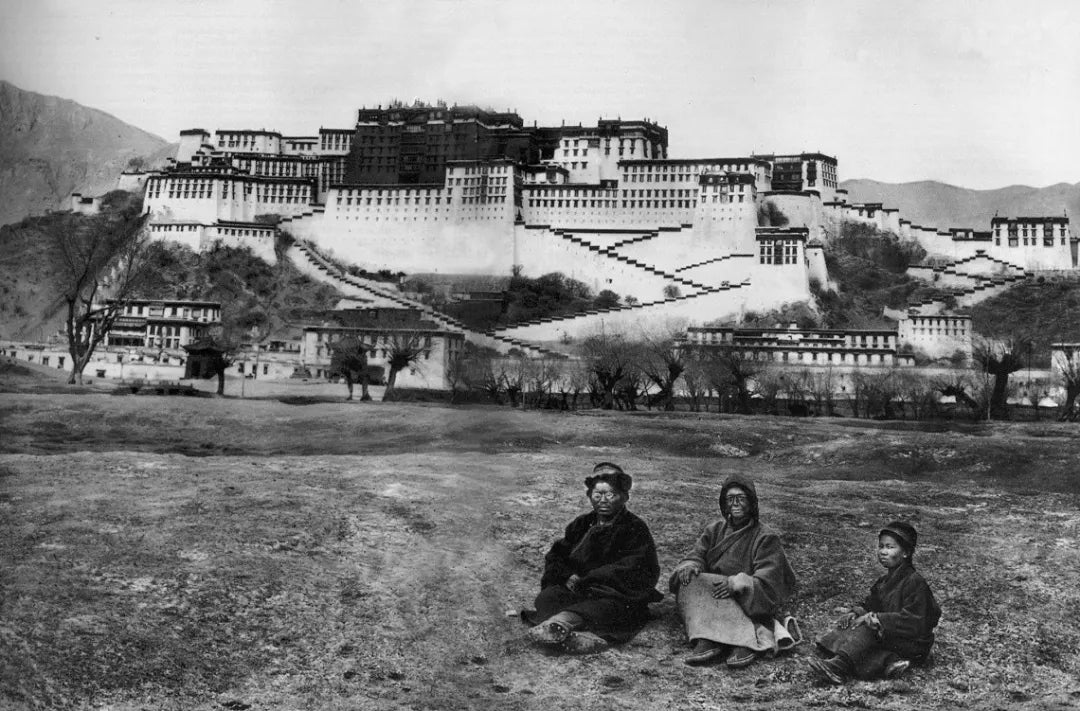

Love for the Untamed Land

Though 19th-century Western explorers had mapped much of Tibet and revealed many of its realities, the land's mystique did not fade—instead, it grew even stronger. By the 20th century, Western fantasies had narrowed their focus to three sacred icons: the Holy City, the Potala Palace, and the Dalai Lama himself. Amidst the West's many exoticized constructs, Tibet emerged as the ultimate canvas for boundless imagination.

This era saw Britain's exploratory fervor persist, while America's frontier spirit and France's chivalric romanticism fueled a surge of travel memoirs. Robert B. Ekvall (1898–1983) stood apart: born near the Gansu-Qinghai border to long-term missionary parents in Tibet, he was fluent in both Chinese and Tibetan and harbored deep affection for the local people. After relocating to the U.S. in 1951, he drew on his memories to write Tibetan Skylines.

The book overflowed with praise for Tibetan character and landscapes—so much so that Ekvall often seemed to shed his Western identity, merging with the local ethos. Unlike superficial adventurers, he captured Tibetan joys and sorrows with intimate, granular strokes. His affectionate nicknames for friends—"Fan-Ear Jiancun," "Flat-Face Renzhen," "Kindhearted Dancho Tsering"—brought them vividly to life. Less a sensationalist account than a nostalgic memoir, the book kindled Westerners' enduring goodwill toward Tibet.

Two editions of "Tibetan Skylines", Farrar, Straus and Young

*Two cover variants of "Tibetan Skylines"*, Farrar, Straus and Young

Alexandra David-Néel (1868–1969), a "heroine" in both Eastern and Western academia, was born in Paris. She studied Sanskrit in Sri Lanka and India, toured Europe as an opera singer, then returned to Asia, traveling through Burma, Japan, Korea, and China. Throughout her life, she harbored an unquenchable passion for Tibet, undertaking four expeditions there. Westerners widely celebrated her daring exploits and adventurous spirit. Her travel diary, My Journey to Lhasa, caused a sensation across the Western world.

*Alexandra David-Néel in Her Youth*, unknown, 1900

*Alexandra David-Néel with Tibetan Monks*, unknown

The book recounts her fantastical adventures—disguising her identity by darkening her skin with charcoal and ink, posing as a beggar to evade bandits on the road, and more. Upon reaching the Holy City, she provided meticulous, scholarly descriptions of local customs, etiquette, religion, ethnicities, urban landscapes, and architectural features. Her writings hold significant historical value while also possessing literary beauty, brimming with a romantic spirit of exploration.

In her prose, every Tibetan vista was both majestic and enchanting; the Holy City embodied a utopian purity and charm. The Tibetan people, she wrote, lived joyfully, their lives as free as birds. Even in the most remote stretches of Tibet, travelers would invariably offer a cup of hot tea to passersby—a simple yet profound courtesy.

"I felt as though I were living inside a romantic novel, one set among the lowest strata of society—a stratum filled with marvels and exoticism! Every one of them basked in the radiant sunlight, living as freely as birds beneath the azure sky. Their souls carried a gene of happiness."

*Alexandra David-Néel Disguised as a Pilgrim Monk*, unknown

*Alexandra David-Néel with Her Caravan*, unknown, 1914

*Alexandra David-Néel and Companion Disguised as Beggars*, unknown, 1924

Geologist Henry Hubert Hayden (1869–1923) was invited by the Kashag to conduct surveys in Tibet. As a scholar, his expedition journal, Sport and Travel in the Highlands of Tibet: A Geological Exploration, largely presented factual, balanced observations. However, one passage describing Tibetan women stands out:

"They mostly share similar features—not delicate, with the Mongoloid type's broad, flat face and almond-shaped eyes. Their skin is slightly fairer than other Easterners', their cheeks rosy, and their hair invariably black. They adore gemstones: women wear elaborate headpieces of jewels, while wealthy ones layer necklaces of emerald, coral, amber, and pearl... Even the poorest wear a golden locket on their chests, containing emeralds and inscribed papers bearing charms, spells, or blessings."

*Tibetan Headdresses* postcard, J Burlington Smith, 1930s

*Mrs. Ringang and Her Daughter*, unknown, 1938

One cannot overlook the botanist Joseph Rock (1884–1962), who never married and, judging from his notes, lacked lasting friendships or romantic bonds. As his biographer S. B. Sutton observed, perhaps his only true love was the untamed land of Tibet itself. Rock’s The Discovery of Dreamlike Shangri-La meticulously documented the religious practices, chieftain systems, funeral customs, and other cultural-geographical features of Tibetan regions in Yunnan, accompanied by extensive photographs. This work ignited boundless Western fascination and admiration for the East. Legend has it that Lost Horizon was inspired by and heavily influenced by Rock’s travel writings.

*Mr. Joseph Rock with His Peonies*, Wikimedia Commons, 2019

*Selected Photographs by Joseph Rock*, *National Geographic Magazine*, 1913

*Selected Photographs by Joseph Rock*, *National Geographic Magazine*, 1913

*Selected Photographs by Joseph Rock*, *National Geographic Magazine*, 1913

The Deeper, The Love Grows

*Alexandra David-Néel in Her Later Years, Writing at Home*, unknown

**References**

1. Li Qiyue, *A Study of Tibet's Image in Western Travelogues of the 19th and 20th Centuries*, Beijing Normal University PhD Dissertation, 2019;

2. Zhao Guangrui, *Tibet's Image of Itself: An Examination Centered on Traditional Vocabulary*, *China Tibetology* No. 5, 2016;

3. Thomas Neuhaus, *Tibet in the Western Imagination*, Palgrave Macmillan, 2012;

4. Hao Shiyuan, *Old Tibet: Western Records and Forgotten Imaginations*, *Ethnic Studies* No. 4, 2008;

5. Martin Brauen, *Dreamworld Tibet: Western Illusions*, Shambhala Publications, 2004.

1 comentario

dkq906