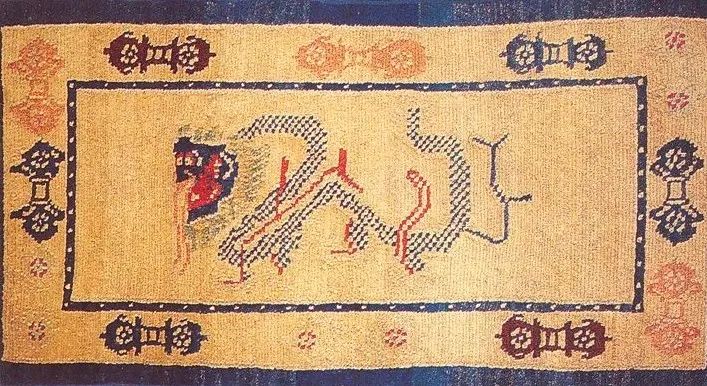

The Tibetan Dragon's Eight Artistic Flash Mobs (Part 1)

"The Four Great Achievers in Bamboo Baga" in the traditional mixed painting style of the Radu region in the mid-late 19th century.

Detail: A auspicious dragon holding a treasure vase offering nectar to the achievers.

They are decorations, but also the very essence of the idea

Behind that image resembling an East Asian dragon

Is the special affection of the local culture for the "dragon theme"

God of Wealth and Dragon

"Legacy of Adi Gorge: Five Deities of White Zhan Bara/White Wealth God"

At the end of the 18th century, the Hahn Cultural Foundation

The central top symbolizes the origin of the teachings: Avalokiteshvara

On the left and right sides are Adi Gorge and Jia Yi Shi

Surrounding the Wealth God are four attendants goddesses

"White Zanbala/White Wealth God Statue"

Mid-18th century, Mongolia, Private Collection

On the banks of the Ganges River, the great master Atisha (982-1055) saw a man who was about to starve to death with no food by his side. He was ready to follow the Buddha's example and offer his own flesh. The man shook his head and said, "I do not eat human flesh, especially not yours; I only ask you to give me a method to increase my fortune and luck." Atisha was moved by the man's words and actions, and tears welled up in his eyes. Not only that, the deity he worshipped, Avalokiteshvara, also shed tears, with the tears from his left eye transforming into the goddess Tara, and the tears from his right eye transforming into White Jambhala and his four attendant goddesses. Without relying on any existing teachings, Atisha received the "White Jambhala practice lineage" directly from Avalokiteshvara.

As the great master Atisha passed on this teaching to his disciple the translator Jampa Sherap Senge, the riding dragon deity became popular in the Tibetan region. The jade dragon ridden by White Mahakala has three meanings. Firstly, the jade dragon symbolizes that the White Mahakala lineage will flourish in Tibet. Secondly, the jade dragon, symbolizing wealth and fortune, is actually the tears of the bodhisattva (this lineage requires water offerings). Lastly, White Mahakala, who rides the dragon, is often associated with changes in weather, and the ritual texts emphasize his special protective power for bountiful crops and sustenance.

Goddess and Dragon

"Brocade Embroidered Thangka: Five Sisters of Longevity and Good Fortune"

Early 20th century, Bhutan, private collection

Central top figure of Milarepa, an important figure in the Kagyu tradition

Partial image: The woman riding the Jade Dragon is Sheren Shan.

"Biography of Milarepa: Milarepa and the Five Sisters of Long Life"

18th century, Ruben Museum collection

The story sequence has been marked by the author in red numbers (1-2-3)

From the indigenous religion of Tibet, the "Manmo" (སྨན་མོ་/སྨན་འཁོར།, a spirit resembling a young woman who roams around villages by mountains and lakes) to the protector deities in Buddhist temples, the classic narratives and prayer rituals of the "Five Sisters of Longevity and Auspiciousness" (ཚེ་རིང་མཆེད་ལྔ) have always been popular in Tibet. As deities of the region and guardians, they were tamed by the master Padmasambhava and vowed to protect the teachings of the Buddha. During the later spread of Buddhism, the Five Sisters had an interesting encounter with the master Milarepa (1040-1123), where the goddesses who had come to test the master became his faithful followers.

The goddesses each have their own mount, and the Goddess of Compassionate Giving rides on a divine dragon. "Protect all cattle and sheep, and ride on the dragon through the oceans of oil and milk"; as a protector of pastures and livestock, the dragon mount of the Goddess of Compassionate Giving has special significance. The snakes symbolizing "Lu" (see previous post) and the long-lived thatch grass growing in the pasturelands foretell abundance of water and grass in the pastures, all of which require the blessing of the dragon. Ritual texts emphasize that the dragon can protect the pastures from earthquakes, frost, hail, and snow disasters, and in some pastures, the herding dogs (usually Tibetan mastiffs) are referred to as the "servants of the dragon".

"Twelve Goddesses Mural: Namtso Vajrayana Mother"

Taken by the author at Gaden Monastery, Mocogar County

(Founded during the reign of Songtsen Gampo)

There are four Dömo (བདུད་མོ། or translated as witches), four Yakṣiṇīs, and four Māmo (as mentioned earlier), collectively known as the "Twelve Danma Goddesses"(བརྟན་མ་བཅུ་གཉིས། or translated as Twelve Earth Mothers). As the female spiritual beings in Tibetan indigenous beliefs that stabilize the four directions and bring harmony to all beings, traditional scriptures say they were tamed by Padmasambhava. There are three main lineages concerning them: general Dharma protectors rituals (mostly in the Gelug and Kagyu traditions), attendants of White Tara, and the revealed treasure tradition in the Nyingma school (particularly the tradition of Mindrolling Monastery).

The goddess Jangma Yungmo (རྡོ་རྗེ་ཀུན་གྲགས་མ།), also known as the Radiant Queen, resides at Namtso Lake, holding a clear mirror and a water monster banner, with a turquoise jade dragon under her seat. It is worth noting that in early ritual texts, no goddess is depicted riding a dragon, and in some later texts (such as certain lineage transmissions of the Zhugaba sect), the goddess riding a dragon is not Jangma Yungmo. The dragon that Jangma Yungmo rides floats on the surface of Namtso Lake, commanding all aquatic beings with the water monster banner, and using the clear mirror for divination. The dragon is the embodiment of the sacred lake's creatures, while the goddess is the soul of the sacred lake, and when they unite, it brings good fortune.

Water monster and dragon

Partial image: Two Danma goddesses (right is the mother of King Kong Mingyang)

Partial image: Three long-lived goddesses (right is the goddess of kindness)

Mid-19th century, Rubin Museum of Art collection

Whether the Longevity Sisters or the Twelve Danma Goddesses, they were all identified as attendants of the Goddess of Good Fortune after being influenced by Buddhism. In this fifteenth-century painting, seventeen goddesses surround the main deity, the Goddess of Good Fortune. The two goddesses mentioned earlier, who ride on dragons, namely Vajra Utmost Praise Mother and Sheren Good Deeds Female, are also depicted accurately. However, this image also reveals a confusion in the early painting tradition of Tibet regarding several similar themes, namely Tibetan dragons, South Asian water monsters (ཆུ་སྲིན), and the face of glory Zhibaza (ཙི་པ་ཊ or ཙི་པ་ཏ). The water monsters and Zhibaza have been extensively researched in previous articles by the author (readers can revisit the past articles at the end of this article).

The high arched and curved nose and body full of granular texture that do not belong to dragons are depicted in paintings, early temple murals, and religious decorations. This expression was rampant in the works of the creators of Oel Temple, Kunga Sangpo (1382-1456), and Petön Panchen (1376-1451). With the introduction of the dragon image from East Asia, people seemed to have found a great way to distinguish these beings. However, even today, people still mistake a deer for a horse.

Decoration and Dragon

Unlike the dragons in local beliefs and religious rituals, the dragons that appear in Tibetan decorative arts often have a hint of East Asian color. Whether it's Tibetan rugs, chests, temple utensils, or costumes, dragons are seen as symbols of supreme authority and hidden spaces. The 8th Dalai Lama, Jampel Gyatso (1760-1810), who served as regent, once classified Tibetan rugs with animal motifs into five categories, namely the double deer rug symbolizing the teachings, the tiger rug symbolizing the diamond mind and masculinity, the snow lion rug symbolizing practitioners, the frog rug symbolizing auspiciousness, and the dragon rug symbolizing special identities. In the political and cultural exchanges between the Central Plains dynasties and Tibet, the unique significance of East Asian dragons has been internalized into the local dragon culture, whether sacred or secular.

Dragon displays prosperity, announce to all directions.