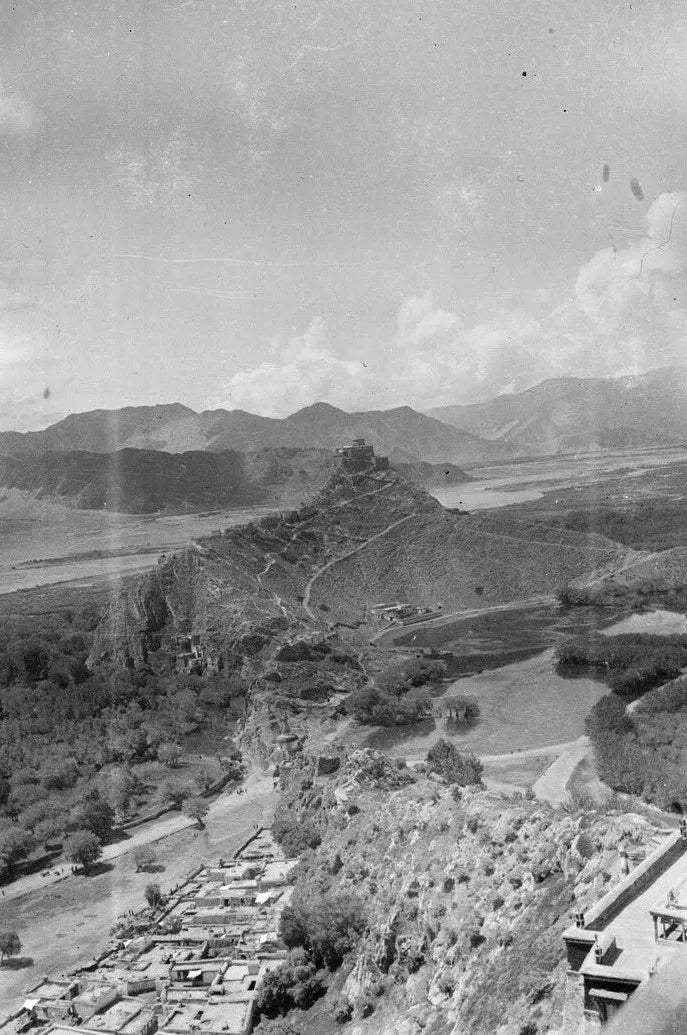

Medicine King Mountain (Part II): The Secret of the Architectural Complex

Mid-19th century, Royal Ontario Museum Collection

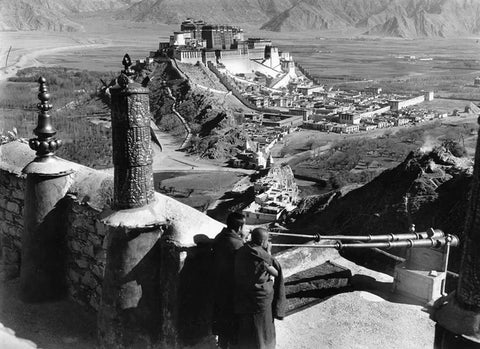

Detail: Potala Palace complex

Note: Clearly visible cylindrical red wall towers

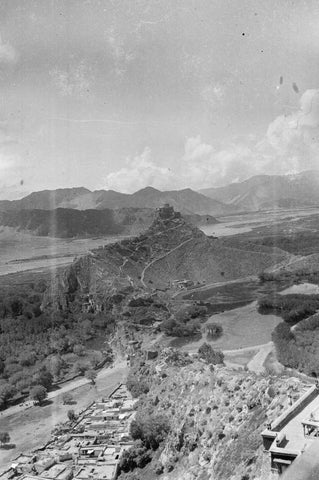

1937, held by the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford

Taken by the team of Li Jisheng (1905-2000)

Co-authored by Robert Gerl and Jürgen C. Aschoff

This book is a masterpiece on the social and individual history of Tibetan medicine.

Preface

"The main statue in the Chalalup Temple on Medicine King Mountain"

Around 1921, in the collection of the Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford

Photographed by the team of Charles Bell (1870-1945)

Furthermore, even if we are aware of basic information about the interior of the architectural complex, such as the Coral Decorated Infinite Life Buddha statue in the Temple of Early Achievements (*གྲུབ་ཐོབ་ལྷ་ཁང་*), the new construction of the main hall by Regent Sanggye Gyatso using twenty pillars, or the altar dedicated to the renowned Tibetan, Mongolian, and Han doctors; such historical records cannot help us understand the basic layout of the mountain roads on Medicine King Mountain, the actual layout of different functional buildings, and how people study and live in the buildings. Therefore, visual and oral historical materials are key resources for researching the architectural complex of Medicine King Mountain. In this translated text, Knud Larsen will use oral history and visual materials to try to materialize speculations and provide suggestions for "rebuilding the architectural complex of Medicine King Mountain". As in the previous article, symbols denoting images used in the original English text will be marked with an asterisk (*), and the translator will provide explanatory notes for some content.

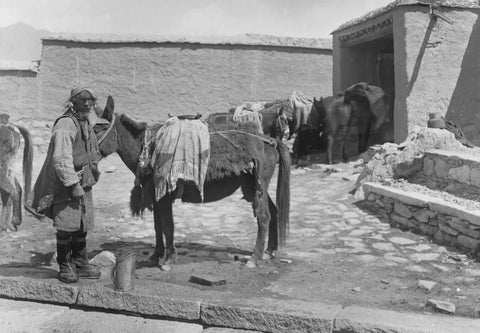

"A muleteer waiting to obtain the holy spring water at Yaowang Mountain"

Around 1921, Oxford Pitt Rivers Museum collection

Photographed by Charles Bell (1870-1945) team

Text

After completing the set of architectural drawings of the Medicine King Mountain in 2009, there was no progress in this research until 2012. In the summer of 2012, I happened to meet Theresia Hofer in Oslo. She was a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oslo and had written papers on Tibetan medicine. The Rubin Museum was planning an exhibition called "Balancing the Body: The Art of Tibetan Medicine," which Theresia was working on. I told her about the idea of reconstructing the Medicine King Mountain Medical College, and she invited me to participate in the exhibition at the Rubin Museum. I contributed my drawings to the exhibition and became the author of a chapter in the exhibition publication. I titled the chapter "Pillars of Tibetan Medicine: The Medicine King Mountain and Men-Tsee-Khang Medical College in Lhasa."

"Mo Ya Shi Ke on the south side of Lhasa Medicine King Mountain: White Tara"

From "Mo Ya Shi Ke on Medicine King Mountain" (1996)

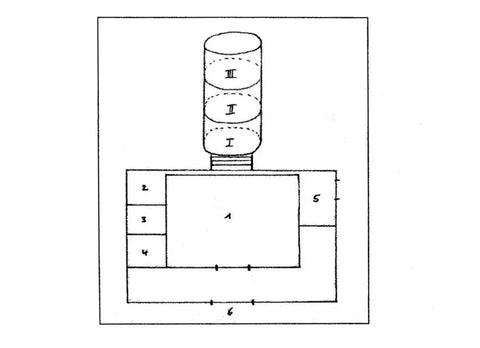

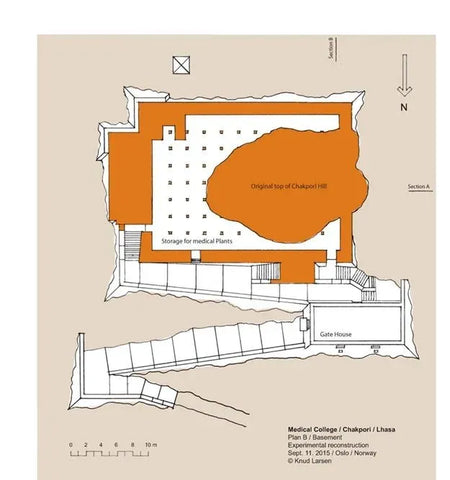

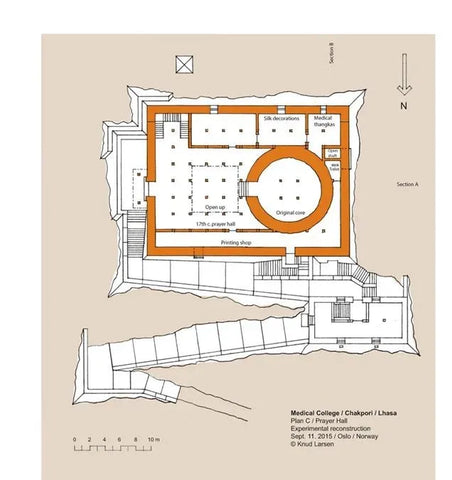

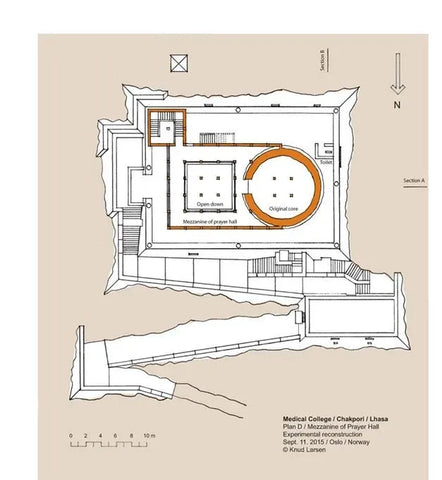

The German publication mentions the twenty pillars in the central hall. For those familiar with Tibetan architecture, "twenty pillars" means that the pillars in the hall are arranged in a four by five layout, with spaces between the pillars measuring five by six (approximately 2.4 meters each). This space, approximately twelve by fourteen point four meters in size, is ideal for the central hall. Another important piece of information in the book is a sketch of the main building layout (Figure One). In 1997, after interviewing Dr. Danzeng Baijue, scholars created the sketch. The sketch depicts a main hall with rooms on both sides, connected to the original tower. There is a short staircase leading from the main hall to the tower. The tower consists of three levels, and no other staircases are shown in the sketch. Staircases inside the tower would take up too much space. Therefore, people at that time must have entered the tower from the outside (via the mezzanine in the main hall), a common design seen in many temples. Alternatively, they could have entered from the roof, another common design.

*Image 1: Sketch drawn after interview

Provided by Danzeng Baijue in 1997

1. Main hall 2. Storage room for Tibetan medical thangkas

3. Storage room for silk decorations 4. Purpose unknown

5. Printing room with side door 6. Main entrance of the main hall

Photographed by Schuyler Jones in 1986

Collection of Pitt Rivers Museum, Oxford.

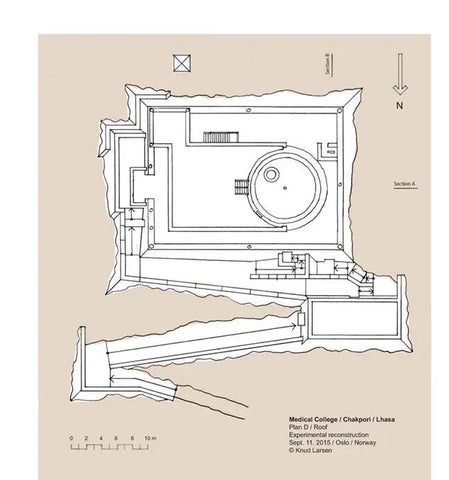

The photos taken by Wanis show that in the southeast corner of the hall, there is a smaller space extending to the roof, possibly the location of an internal staircase. This is common in many temples. These stairs lead to a mezzanine, which is a common design feature of the hall. The mezzanine provides lighting for the hall and leads to the first floor of the tower. It is difficult to determine if the main staircase also extends to the top of the mezzanine. If not, there is likely a lightweight staircase placed in the secondary room to access the roof, commonly seen in temple rooftops. The height of each floor of the tower is roughly the same. In any case, there may be another small staircase on the roof to access the second floor of the tower, which is common in Tibetan structures such as the Xialu temple. In the photo, there appears to be a pole in the center of the tower. In my initial design concept, it was indeed used to support the roof of the tower, similar to the wooden core pillars of a stupa, but it may also just be part of the roof. In the final design, I considered the possibility of a central pillar supporting the floors and roof of the tower; therefore, I concluded that there must be an internal core structure in the tower, consisting of four interconnected pillars.

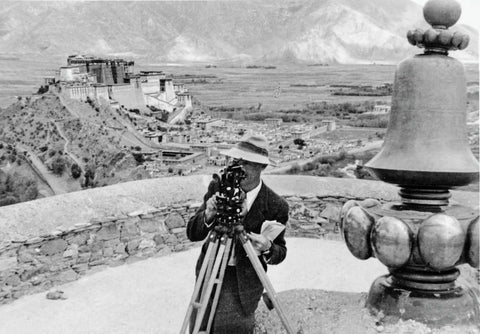

*Image 2: "Peter Aufschnaiter at the Summit of Medicine Buddha Mountain"

Photographed in 1948 by Heinrich Harrer

Peter Aufschnaiter (1899-1973), a mountaineer and geographer, is conducting geographical surveying at the summit of Medicine Buddha Mountain.

When I was looking at a photo taken by Hal, I found the answer to this question. In the photo, Peter Ofschnait stood on the roof and looked at the instrument on the tripod (Image 2). The so-called "pole" is actually a copper decoration in the center of the roof. Hal's series of photos taken in Lhasa in 1982 showed the ruins of a building. One was taken from the northeast (Image 3) and the other from the southwest (Image 4). In the former, the slope is easy to identify. The openings on the north facade indicate the positions of former small windows, a door next to the staircase in the middle of the east facade leads to the basement; and the tower window facing the Potala Palace can also be seen. The latter shows the windows on the south facade, as well as the relationship between the tower and the west wall. Upon zooming in on the photo, it can be seen that there is a horizontal gap above the rocks on the west wall. Below this gap, there are traces of contamination on the rocks: flowing out from the gap and running down along the rock wall. Without a doubt, this is a toilet. The building definitely had a toilet, there was a toilet near the main hall printing room, and there was also an outdoor toilet on the roof, separated by a wall between them.

Photographed by Heinrich Hahler in 1982

Some wall surfaces may date back to the Tang Dynasty period

Photographed in 1982 by Heinrich Haller

The architectural design does not obstruct the view of the mountain structure.

Taken by Spencer Chapman in 1937.

Filmed by Ernst Schäfer in 1939

One of the most important visual materials for the reconstruction plan.

Taken by Ernst Schäfer in 1939

In the distance, the dormitories of the college and a pathway leading down the mountain are visible.

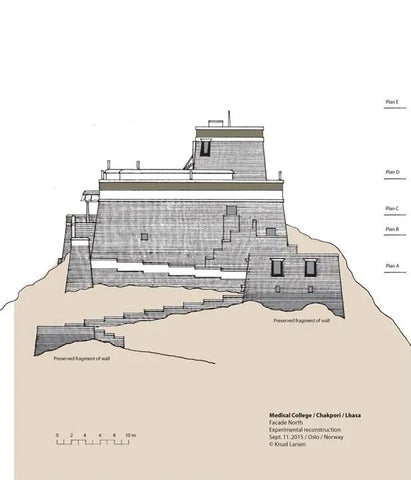

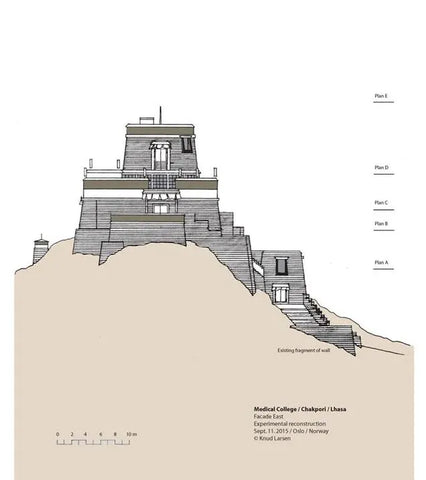

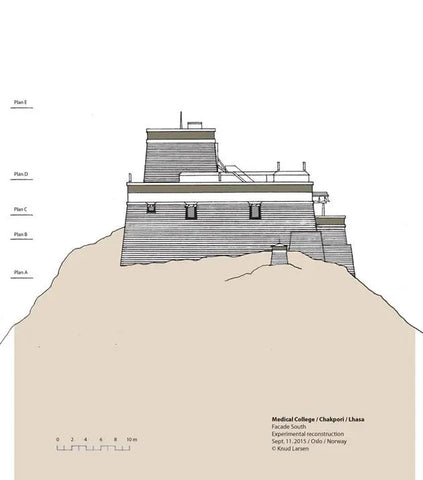

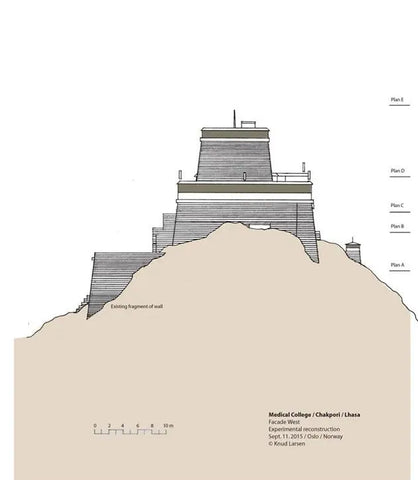

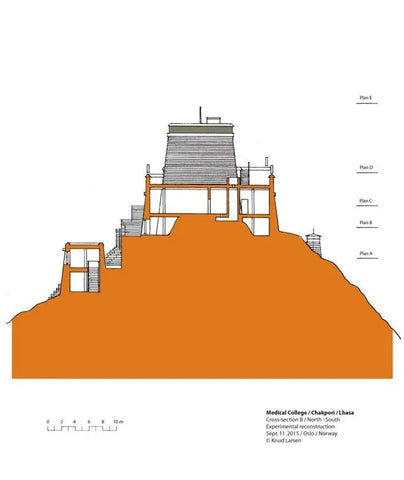

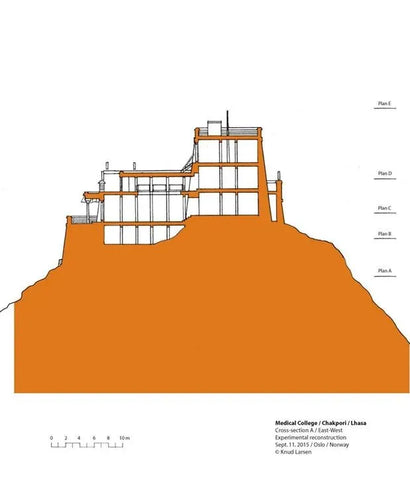

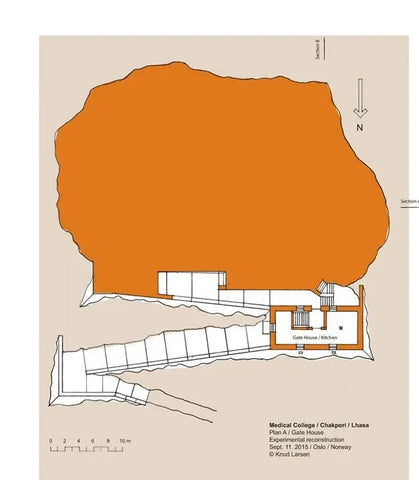

Drawn by Knud Larsen in 2015.

Drawn by Knud Larson in 2015

2015, illustrated by Knud Larsen

Drawn by Knud Larsen in 2015

Drawn by Knud Larsen in 2015

Image 13: "Medical College Reconstruction Plan of Yaowang Mountain: East and West Facades"

Drawn by Knud Knudsen in 2015

At the end of the article, I want to tell you about a wonderful coincidence. In September 2015, I spent a few days in Chengdu. During that time, a friend invited me to have dinner with some of her friends. One of them was a former soldier who had been stationed in Tibet. He quietly told me that he might be more familiar with the building than many others. When he first entered Tibet, he was only seventeen years old. Later, he became a doctor in the Shigatse area. It is worth mentioning that he had once been the personal physician of the Panchen Lama. He wished me luck in my "reconstruction plan," and I felt that this was a good omen: the cycle of destruction and reconstruction was about to come to a close.

Drawn by Knud Larsen in 2015

2015, illustrated by Knud Larsen

Drawn by Knud Larsen in 2015

Drawn by Knud Larsen in 2015

Drawn by Knud Larsen in 2015.

Illustrated by the artist Tsering Tashi