What is the use of this iron rod? ▎Tibetan Iron Rod Monk

Secular Edge

Dim light, crimson robes, swirling incense, deep chants, even the fierce faces of the wrathful deities... These religious elements come together to create a mysterious and sacred enclosed space, where the solemn atmosphere pervades everywhere. It reveals a cold gaze towards the secular world, as if urging the passing believers to realize the impermanence of all things, the suffering of all attachments, and the ultimate truth of the world without self. It also represents the ultimate goal of Nirvana, full of silence.

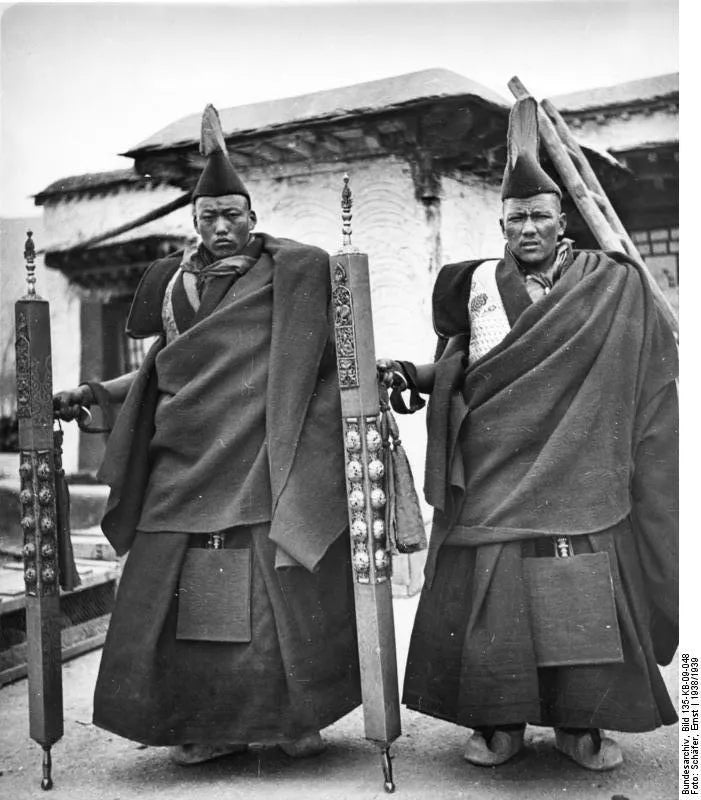

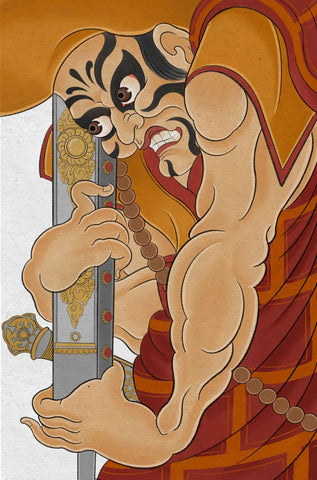

It is within such a sacred space that there is a figure, as if condensed with all the majesty. He holds a square iron rod, draped in a heavy scarlet cloak, pacing back and forth among the rows of monks. With each step, he strikes the iron rod heavily, the crisp sound proclaiming the strictness of the discipline. He is the monastery disciplinarian - Iron Rod Monk!

Image source: wikimedia

Iron Rod Monk

In this Vinaya text, the Buddha specifies the duties of this position as sweeping dust off seats, and Japanese scholar Takeuchi discovered in an analysis of a Dunhuang document (Pt.1119, currently held in the French National Library) that Gegyi was also responsible for borrowing and lending grain from the temple granary. In this document, he found two seals, one likely belonging to the borrower of grain, and the other presumably the seal of the Gegyi at that time. This indicates that the term "Gegyi" became associated with disciplinary roles in Buddhism later on.

Monk Manager

Jai (བཅའ་ཡིག) is the system of rules and regulations in Tibetan monasteries. In the earliest set of "jai," the term "gegyu" was not used, but other nouns were used to represent the maintainers of monastery discipline, such as "panniwa" (བན་གཉེར་བ), which translates to "supervisor of monks."

The Tashilhunpo Monastery (འབྲི་གུང་མཐིལ) is a famous monastery with a long history in Tibet. In one of the jai texts of this monastery, it clearly states, "You panniwas must supervise the study of scriptures and rules for new monks." The author of this jai is believed to be Khendzong Nga (སྤྱན་སྔ་གྲགས་པ་འབྱུང་གནས། 1175-1255), who served as the fourth abbot of Tashilhunpo Monastery from 1235 to 1255. Therefore, this set of rules is likely written during this period. Based on this evidence, Berthe Jansen suggests that the term used for the maintainer of discipline emerged after the 15th century.

Tashilhunpo Monastery, 2005

Photo by Mark Evans

Source: Wikipedia

As the disciplinary officials in the temple, the monks such as Ge Gui also participate in the drafting of temple regulations, and it is their responsibility to recite the regulations (known as jae in Tibetan) in public on specific occasions and times. For example, at the Gerdeng Monastery, there are two sessions of reciting the regulations during the 8 annual courses held each year. Furthermore, during the Lhasa Prayer Festival, the monks from Drepung Monastery would carry the monastery's regulations on their shoulders for a procession in the main hall.

1957 Lhasa Prayer Meeting

Photograph by Chen Zonglie

The monks patrolling and maintaining order in the main hall of Zhebang Temple.

Tashi Lhunpo Monastery, the abbot of the Great Hall, is known as the Mani Association. He is the most representative Geshe in the Tibetan language. According to tradition, Je Tsongkhapa (1357-1409) personally transmitted the disciple Jamyang Qoigyi Zhabdan (1379-1449) who founded Tashi Lhunpo Monastery, which initially had only eight monks. One day, during a daily ritual in the monastery, the eight monks began pushing each other and one of them was injured in the leg. Seeing this, Jamyang Qoigyi Zhabdan said, "Today, with such a small number of people, we have such a crowded situation. This is an auspicious sign. In the future, countless disciples will come here in a continuous stream." He immediately ordered the selection of a Geshe to oversee discipline, and the iron rod used by the Geshe at that time is still kept in the Manjushri Temple of Tashi Lhunpo Monastery.

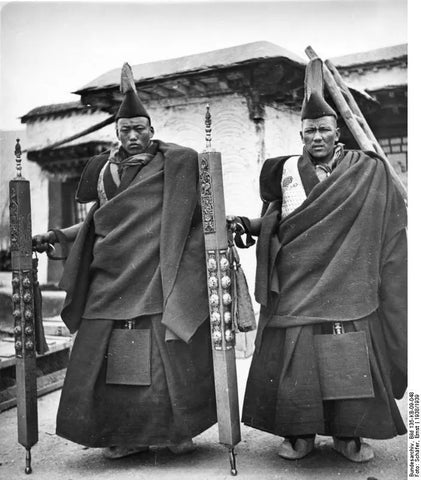

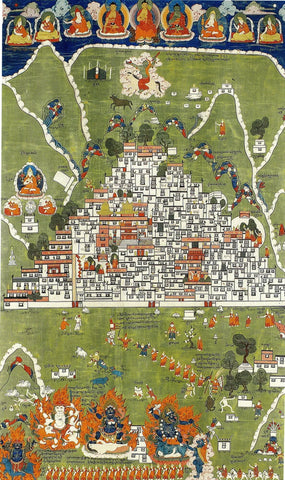

"Panorama of the Temple of Philosophy: Folk Celebration," late 18th century

Royal Museum of Art and History, Belgium

The election of the chief monk in the main hall of the Tashilhunpo Monastery involves a highly complex process and ritual. The election process begins in early June of the Tibetan calendar, with the selection of 2 co-chiefs. At that time, each of the 10 specific departments of the Tashilhunpo Monastery nominates a candidate to participate in the preliminary examination. After the preliminary examination, all candidates must travel to Loblingka by June 15th to take the final examination. After all exams are completed, the candidates return to their respective monastic residences to await the results. The results of the examination will be announced by two messengers, and as a auspicious sign, the selected candidates will treat the messengers with yogurt, ginseng fruit, and other foods. The messengers will then determine the chief and deputy chiefs based on their qualifications.

"Panoramic View of the Zebi Temple", 1898

Collection of the Rubin Museum of Art, New York

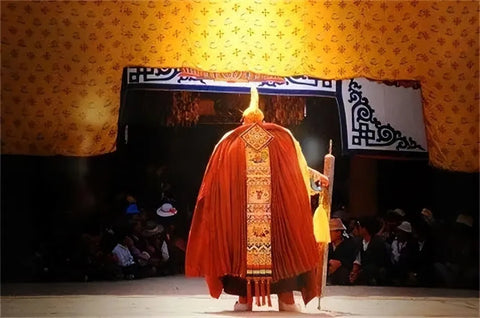

The Shoton Festival begins on the 29th day of the 6th month in the Tibetan calendar, and at Drepung Monastery, a Tibetan opera performance will be held in front of the steps of the Gaden Podrang. Both the outgoing and incoming kyorpon are required to attend, with the outgoing kyorpon dressed in full monk attire and accompanied by monks, while the new kyorpon wear simpler clothing. On the 30th of June, at the Potala Palace, a giant thangka will be displayed during a ceremony and the new kyorpon will be officially appointed. Alongside the Tibetan opera performance and other activities, the two new kyorpon will hold the iron rods for the first time under the guidance of monks, and after the thangka ceremony, they will lead the thangka back to the main hall at the front of the procession, where they will also sit in the kyorpon seats for the first time. An interesting sight is that when the new kyorpon take their seats, the outgoing kyorpon are extra cautious, as some monks who were offended during their tenure may seek revenge.

1992, at the Jokhang Temple in Lhasa

Source : flickr

Wearing a red robe, holding an iron rod

Unlike the general monks, in order to highlight the strictness and dignity of the Dharma, their attire has many characteristics: they wear a red and yellow silk undershirt underneath, covered by a kanjur, and padded with a one-foot long shoulder pad called "apo" (ཨ་འབོག), and an outer layer of crimson woolen robe. They wear a high-quality zhedangbiji monk skirt, woolen boots, and a pointed high hat. During important gatherings, they wear a crimson cape adorned with various embroidered long strips and buttons (སྒྲོག་ལུ), a golden gawu box (གའུ) on the neck, and hold an iron rod with gold edges, solemnly and heavily moving around the hall.

Image source: Internet

He is not only an enforcer of the law, but also a subject under the rod.

The main responsibility of the Gé Gé is to monitor the daily discipline, such as whether the monks' attire is appropriate, their behavior is civilized, and sometimes he is also responsible for the monks' leave matters. In the past, the Tax Administrator of Jyelpa Monastery also had the responsibility of collecting taxes - there were often small businesses operating in the monastery, and at this time the Tax Administrator would collect taxes from them, the specific standards are unknown, but according to the "Selected Historical Texts of Tibet", a tax rate of five qian per jin of beef was collected from butchers. During the annual winter puja, the two administrators faced the obligation of offering alms, and therefore would collect more taxes at this time. Although the annual tax collection is not fixed and has some fluctuations, the administrators always receive a considerable income through these tax collections.

Image source: Buddhist Culture

In conclusion, all the disputes in the monastery require the intervention and judgment of the disciplinary officials, and their guiding principle is the monastery rules. At the same time, the monastery rules and the monks demand that the disciplinary officials must maintain fairness and strictness. For example, in a text from the Dzongkar Tashilhunpo Monastery, it is written that if a violator escapes punishment due to the negligence of the supervisor, the supervisor must bow five hundred times as a penalty; if it is due to the neglect of the inspector, the inspector must bow one thousand times as a penalty.

There is also a harshly worded reprimand letter from the Thirteenth Dalai Lama to two disciplinary officials, blaming them for neglecting their duties and demanding immediate rectification: "Know that the welfare of sentient beings depends on the monks, especially the strict observance of the rules in the three great monasteries... Yet you, as enforcers of the law, have been lax in your duties, allowing a group of wrongdoers to not only brazenly harm the interests of sentient beings and the reputation of the monastery, but also squander their own accumulated merit, indulging in worldly pleasures such as alcohol, tobacco, gambling, camping in the summer, gathering in the halls in the winter, wearing inappropriate attire, and so on... You, as teachers and disciplinary officials, have long been guilty of this, but thought you would repent and change, hence you have not been reprimanded until today... If there is any further negligence, you will face the dire consequences of self-destruction of both reputation and reality. This stern warning is not to be taken lightly." It is evident that even the sternest of monks must maintain a sense of fear and reverence in order to safely navigate the edge of the world and protect the monastery's monks.

Sadao Guishou's work "Iron Rod Monk"

What use does this iron rod have

for me?

- With awe, with strictness

Reference: