Fruits of the Himalayan Classical Period (Part 1): Apples, Peaches, Plums, Walnuts, and Pears

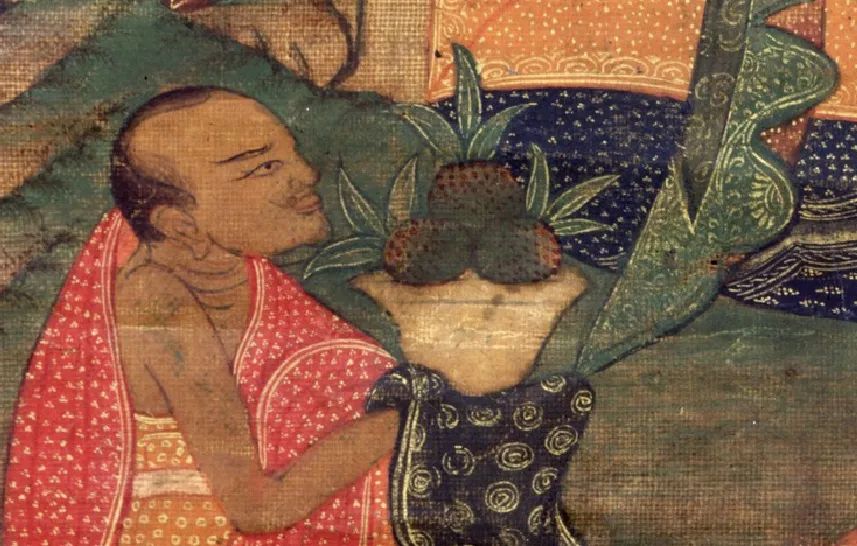

"The Great Achiever Avalokiteshvara and Various Dakini Masters"

Late 17th century, Rubin Museum of Art

Detail: Possibly a fruit of enlightenment, a papaya or a citrus fruit

Note: Avalokiteshvara (the founder of the Dakini teachings) - ཨ་ཝ་དྷཱུ་ཏི་པ།

"The Great White Umbrella Cover Buddha's Supreme Attainment Mother"

Mid-19th century, Nepal region, in the Ruben Museum

Detail: Offering pattern of "Three Fruits in One"

"The Red Pine Vases and Various Offerings to the Buddha"

From the mid-19th century, in the collection of the Rubin Museum

Detail: Objects on the altar used to symbolize the three delights of color, fragrance, and taste.

The fruit of wisdom, with its fragrance, color, taste, and method, is desired by all, be it humans, gods, monks, or laypeople.

Kings and subjects have left behind songs and verses about these fruits, symbolizing deep teachings.

The hidden wisdom of the tantric masters is embedded within the fruits.

Whether native or foreign, real or virtual, the truths of these fruits are profound.

When the celestial maidens offer the three-in-one celestial fruit platter, the fragrance lingers, the color shines, the taste satisfies, and the nature of the teachings becomes clear.

The concept of "three-in-one fruit" is related to the three worlds, three treasures of the Buddha, and the three realms.

In the iconography of the Tibetan tradition, common "three fruits-one body" combinations include: 1 Mango-pomegranate-pear ,2 Apple-peach-pear ,3 Papaya-mango-peach , 4 Orange-pomegranate-pear ect.

The substitution of classical combinations and objects with plants is often seen in tantric texts.

During the Tubo Period, the "Three Masters" were represented by lotus fruit-papaya, Atisha- peaches, and Jigme-phallic fruits.

References to the works of the Third Dalai Lama (1589-1644) provide further insight into these combinations.

The relationship between trees and wisdom has been explored in previous articles, and the botanical series will continue to delve into related topics.

Topics such as flowers, fruits, herbs, vegetables, grains, teas, and hallucinogenic plants will be covered in upcoming articles.

"Western Pure Land",late 19th century, collection of the Rubin Museum

Detail: Offering Goddesses (the one on the far right holding a fruit tray is Vajra Fruit Offering Goddess)

"Sixteen Arhats Group Picture: The Venerable Binhead Lu"

Private collection from the late 17th century

Detail: The fruit tray in the hands of the attendant (kumquat or pear)

The cultivation history of apples and pears in Tibet does not exceed three hundred years.

The cultivation history of small apples (flower red) can be traced back to the 18th century.

The cultivation of large apples began to be widely cultivated in the early 20th century.

Pears are generally believed to have been cultivated in the mid-18th century.

However, the length of cultivation history does not affect the cultural significance of the fruits.

In Tibetan language, apples are called "ཀུ་ཤུ་" (ku shu) or "བིམ་པ་" (bim pa).

The word "bim pa" is derived from the Sanskrit word for female lips, "बिम्ब".

The word "ku shu" is believed to have a complex Central Asian origin.

The classical period of Tibetan areas traditionally classified apples under the plum genus.

Apples were divided into Gongbu apples, Weizang apples, and Kangba apples.

Gongbu apples are large and sweet, Weizang apples have good color but are sour, and Kangba apples are small and tasty.

Unlike apples, pears are called "ལི་" (li) in Tibetan, which is entirely related to East Asia.

In some Tibetan areas, pears are referred to as "small gourds" (ཀ་བེད་ཆུང་ཆུང་).

In Tibetan culture, apples are associated with secular power and male-female desires.

In the folk literature of Weizang, apples are related to "nobility".

Pears, on the other hand, are traditionally associated with longevity or good luck, similar to Han Chinese tradition.

Pay attention to the peach in the hands of Han Buddhist Monk.

"Gandenpa: A Gelugpa Lineage Master"

Late 18th century, Rubin Museum of Art

Detail: peaches on the altar

Note: Gandenpa Trichenpa (1038-1103)

The walnut from Tibet is considered the ancestor of all cultivated peaches.

(it has a smooth surface, smaller peach core and no grain)

Tibet is also one of the core origins of walnuts around the world.

Most fruits of the Prunus genus are commonly referred to as "kham bu" in Tibetan.

While walnuts are called "star kha".

They are generally considered indigenous words in the Tibetan language by scholars.

Classical literature divides Tibetan peaches into "big peach" and "small peach".

The big peach refers to the Han peach (རྒྱ་ཁམ་) and the small peach refers to the Tibetan peach (བོད་ཁམ་).

Both are flat peaches (ཀླུང་ཁམ་), while wild peaches are mountain peaches (རི་ཁམ་).

In Tibetan paintings, scenes of holding peaches and apricots or offering peaches are common.

In Tibetan folk culture, peaches and apricots symbolize prosperity, health, and longevity.

Not only that, peaches and apricots are also associated with deep wisdom and complete practice.

The master of the Karma Kagyu painting tradition, Tangla Zewang

(ཐང་བླ་ཚེ་དབང་;1902-1989)

once said that the Han peach and Tibetan peach would be depicted in different scenarios.

The changing color of peaches (white, yellow, red) can also highlight different levels of teachings.

Similar to peaches and apricots, walnuts in Tibet also have rich symbolism.

In historical materials related to the Tubo, walnuts or walnut trees are often used to signify a good harvest and authority.

The Gelugpa high lama Quwang Zhaba

(ཆོས་དབང་གྲགས་པ་;1404-1469)

once demonstrated his determination and character by planting walnut trees (at Zhebanci) and countered criticism.

The term for fruits of the Prunus genus varies in different regions.

In some areas, cherries (ཅུ་ལི་; cu li) are used to refer to plums, apricots and peaches.

The fruits from Ali region are also separately called "mang'ari's kham bu".

"Lotus Master's Eight Transformations: Sunlight Master"

Late 19th century, in the collection of the Rubin Museum

Detail: A fruit platter full of fruits (offering of food to the accomplished practitioners in the forest)

"Blessed Pattern Combination Floral Tibetan Style Wooden Table"

From a private collection from the late 18th century.

Note: All three patterns feature peaches or peach trees.

As Langchenpa (1308-1364) said,

རྒྱལ་བ་མཆོག་འོས་རིན་ཆེན་ལྗོན་ཤིང་རྣམས། "Offer the sacred tree to the victorious one,

འབྲས་བུ་དུད་ནས་ནགས་ན་ལེགས་པར་འཁྲུངས། All the fruits in the forest are ripe.

ལོ་མ་མེ་ཏོག་དྲི་ཞིམ་ཁ་ཕྱེ་ཞིང། Flowers and leaves blooming with a delightful fragrance,

སྤོས་ཀྱི་བསུང་དང་བསིལ་བུའི་ངད་ཀྱང་ལྡང། The gentle breeze carries the scent."

And we will continue to explore the sacred fruits of the ancient Tibetan classical period.

-Stay tuned-

Fine offerings and sweet fruits