This is how I see it: An Introduction to Early Wooden Bodhisattva Statues in the Himalayan Region (Part 2)

The standing Buddha on the crown

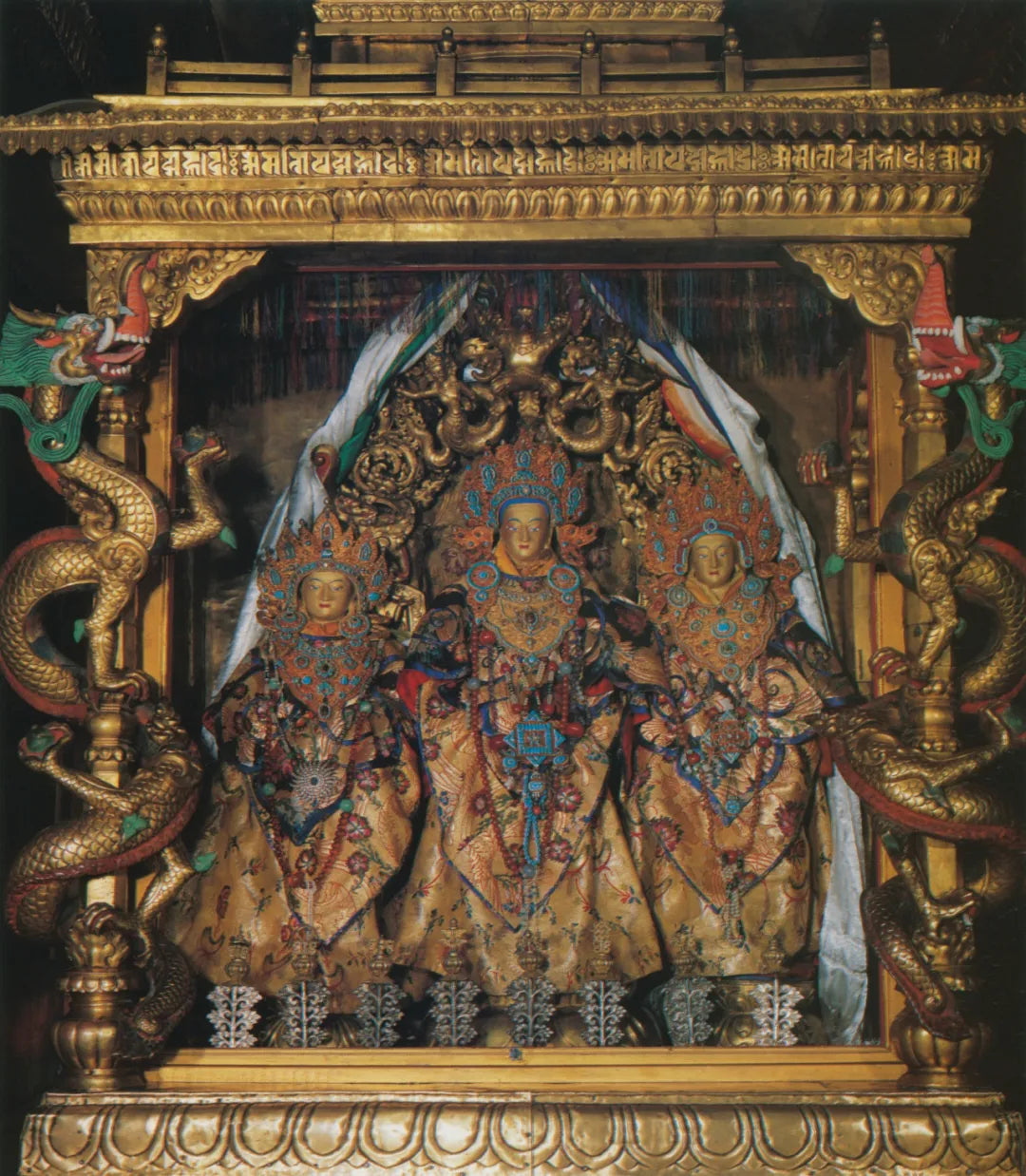

The Padmapani statue in the Potala Palace, also known as the Holy Guanyin statue, is the most legendary Bodhisattva sculpture in Tibetan religious history, and it uses the standing Buddha crown discussed in the previous translation. "Padma" is the Sanskrit term Arya (आर्य; holy or venerable). Similar to the Jowo Rinpoche statue in the Jokhang Temple, it is difficult for people to see the full appearance of the Holy Guanyin statue at the Potala Palace because it is covered with gorgeous robes.

American scholar Ian Alsop fully recorded the painting ceremony of the Holy Guanyin statue at the Potala Palace in 1992, and he had written a classic discussion about the sculpture two years earlier. Observing the photos taken by Ian, it is evident that there is a close connection between the Holy Guanyin statue at the Potala Palace and the wooden Guanyin statue at Lukhang Lhakhang, but there are subtle differences between the two. Except for the ears, there are no special decorations on the other parts of the bodies of the two sculptures. Both Bodhisattvas place their left hand on the waistband, unlike the metal Bodhisattva statue held by Worcester Art Museum, which holds a lotus stem in hand.

Additionally, in the two wooden sculptures, there are differences in the design of the standing Buddha crown; the crown of the Holy Guanyin statue at the Potala Palace is arranged horizontally like the hairstyle of an ascetic. Another aspect to pay attention to is the design of the right arms of the two sculptures: the right arm of the Holy Guanyin statue at the Potala Palace appears somewhat clumsy (taking into account the complex conflicts and later restorations that the sculpture has undergone), while the right arm of the wooden Guanyin statue at Lukhang Lhakhang elegantly extends. It is believed that the Holy Guanyin statue was requested by the Tubo King Songtsen Gampo, leading scholars to designate it as a work from the 7th century in textual writings.

The sculpture has been painted multiple times, but in terms of overall style, traditional interpretations are not inappropriate. Even if we ignore scientific data, the Turin Bodhisattva statue and the Lukhang Lhakhang Bodhisattva statue are both older than the Holy Guanyin statue; especially the Lukhang Lhakhang Bodhisattva statue may be the stylistic prototype of the Holy Guanyin statue. The crown of the Lukhang Lhakhang Bodhisattva statue is sturdier than that of the Holy Guanyin statue, and the bun of the Holy Guanyin statue is more prominent than the crown, these differences may be due to artistic preferences rather than stylistic differences.

【Note 1】: In the art of the Peacock Dynasty, deities wore crowns. It was not until the Gupta Dynasty that crowns became a standard part of deity imagery. In Buddhist art from the Gandhara and Mathura periods, Bodhisattvas still wore crowns. However, by the 5th to 6th century AD, crowns started to be used in Bodhisattva statues and some Buddha statues. It is almost certain that crowns and accompanying elaborate clothing were introduced to the Indian subcontinent from West Asia.

Photographed by Ian Alsop in 1992

Photographed by Ian Alsop in 1992

Similar to the story of the "heavenly object" (occurring during the rule of King Trisong Detsen of Tibet), stories with similar plots are not uncommon. According to research by Alexander Soper, as early as the end of the Northern Wei Dynasty (428-431), there was a similar story. People prayed to Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva due to the cruel rule of the Northern Wei Dynasty. One day, the ruler saw something descending from the sky, and it fell to the ground behind a pillar. Upon inspection, it was found to be the Amitabha Sutra, and the ruler was pleased and pardoned many death sentences. There may be a connection between these two stories in Tibet and the Central Plains.

When consulting the studies of East Asian art by Alexander Soper, the issue of the "standing Buddha" is addressed. Soper referenced a passage from the "Visualization of the Buddha of Infinite Life Sutra" translated by the Japanese scholar Junjiro Takakusu in 1895. As Soper described, "In a sense, the special relationship between Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva and Bodhisattva Mahasthamaprapta in this Pure Land is emphasized," which is different from the content of later texts concerning the Western Pure Land. Soper further pointed out that it is in this sutra that we find the first iconographic description of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, which is different from the familiar seated or meditative forms known to the world later.

I will directly quote the relevant text translated by Junjiro Takakusu here: "This Bodhisattva has a height of eighty thousand nayutas of kotis of yojanas; his body is of a golden purple color, he has a flesh bun on his head, a round light on his neck, and a hundred thousand kotis of yojanas on his face (...) On his crown, there is a standing transformed Buddha, twenty-five yojanas high." Thus, the artistic inspiration of Newari craftsmen is perfectly blended with the Bodhisattva image in Buddhist scriptures in the wooden sculptures of the Himalayan region. It is worth noting that, unlike the general descriptions (red), the scripture describes the color of the Bodhisattva's body as "golden purple". However, the image of Bhrikuti at the Boudhanath Stupa is adorned with a golden outer garment.

18th century, in the collection of the Newark Museum.

16th century, Rubin Museum of Art

In another early Buddhist scripture concerning Avalokiteshvara, there is no mention of any visualization. In the year 420 AD, the scholar Nandi from India translated the "Invocation to Avalokiteshvara to Eliminate Poisonous Elements Sutra" into Chinese to pray for the Bodhisattva to resist evil poisons. When the Buddha was preaching in Vaishali, a great epidemic struck the people of the city and they sought the Buddha's help. The Buddha said, "Not far from here, to the west, there is a Buddha called Amitabha, also known as Immeasurable Life. He has a Bodhisattva named Avalokiteshvara and Mahasthamaprapta. They constantly show great compassion and mercy to all beings, helping them in times of suffering. You should now prostrate yourselves with your whole body in front of them, offer incense and flowers, recite their names and concentrate your mind for ten breaths. For the sake of all beings, you should pray to these Buddhas and two Bodhisattvas."

Amitabha Buddha, also known as Immeasurable Life Buddha, and the mantra translated by Nandi may correspond to a great epidemic that he personally experienced, or a real event that occurred during the Buddha's visit to Vaishali. Such prayers gave rise to the Buddhist tradition of protective sutras (Pancaraksha; five protections) or dharanis, where people believe Avalokiteshvara is an extraordinary protector who saves them from the eight calamities. Around the 6th century, Buddhist followers in Nepal were familiar with the textual descriptions of Avalokiteshvara and created artworks like the wooden Avalokiteshvara statue found in Longkolo Niwase, which later directly influenced the sacred Avalokiteshvara statue in Boudhanath. As evidenced by numerous later replicas, the Bodhisattva statue became popular in Kathmandu (seemingly limited to the Licchavi period).

savior

It is necessary to discuss the process of change in the concept and imagery of Bodhisattva when analyzing the Bodhisattva crown on the Bodhisattva statue. It is well known that Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva has undergone changes on many levels (such as being transformed into a different gender in East Asia), but he remains the most revered deity after the Buddha. Due to the inclusion of "iśvara" (ईश्वर) in the title of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva, some scholars are happy to compare him with Shiva. In fact, the attributes and functions of Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva are more similar to Vishnu than Shiva. Like Vishnu, the Bodhisattva is depicted with a crown and a lotus flower, which is one of Vishnu's most important image characteristics.

Avalokiteshvara Bodhisattva is the compassionate observer of the world (avalokita), known as the "Great Compassion" (महाकारुणिक). If the suffix of the Bodhisattva's title is derived from Shiva, then the prefix, meaning "to look around the world", is closer to Vishnu's attributes. Perhaps to distinguish the Bodhisattva as the heart-son of Amitabha Buddha and not the Buddha himself, the hairstyle of the Bodhisattva is not upright like a crown, but rather rolled horizontally to the sides. At the same time, the Bodhisattva is adorned with a conical high crown, similar to Vishnu's "kirita mukuta" (symbolizing royalty and supremacy).

"Vasudeva-Vishnu" (वासुदेव - विष्णु) gained fame as the supreme deity of the "Bhagavata-Pancaratra" (ভাগবত - पञ्चरात्र; the main worship of Vishnu's various incarnations) around the 2nd century BCE, and the "Bhagavad Gita" was composed during that time, with "Bhagavan" also being a term used in early Buddhist texts to refer to the Buddha. The concept of "incarnation" (avatara) widely seen in works like the "Bhagavad Gita" was inherited by early Buddhists, who believed that past Buddhas reincarnated as Shakyamuni Buddha (similar to the lineage of 24 ancestral masters in Jainism).

"Pishnaka Lying on the Dragon King Ananda"

"Pishnaka Lying on the Dragon King Ananda"Approximately the 10th century AD, Rubin Museum of Art

Mid-18th century, Rubin Museum collection

Approximately 7th century, Nepal region

Height 50.2cm, held in the Gold Bell Art Museum.

Collected by the Bellis family in the 18th century.

To my knowledge, this is the only standing Buddha statue with the inscription gaṇḍabimba. The term gaṇḍa can mean cheeks or grand, and this inscription may signify "magnificent image." Just as we see in the visualization of bodhisattvas in the Contemplation of Infinite Life Sūtra, the imagery of the bodhisattvas is also grand and immense. It is not surprising that the Newar Buddhists associate the image of the standing Buddha with the descent of the Buddha from the heaven, as it is very rare in other Buddhist art. It is worth noting that the standing Buddha was quite popular in the art of the Lopburi period in Thailand. Earlier, the Buddha was depicted standing or sitting on the back of a divine bird, similar to the image of Vishnu as the savior riding on Garuda, and the story of Queen Maya's dream of the white elephant also reflects the concept of "descent from the heaven."

Conclusion

We must assume that the statue of Avalokiteshvara hidden in Lunkholoni is the earliest and finest wooden sculpture known in South Asia. Although legend claims that the tradition of making wooden sculptures can be traced back to the time of the Buddha, when King Udayana of Vatsa made a sandalwood statue of the Buddha on his way to the heavens to preach to his mother, as with many early religious customs of the Vedic era, the deeds of the Buddha also influenced the Newar community in the Kathmandu Valley. From an aesthetic point of view, it is clear that the statue of Avalokiteshvara hidden in Lunkholoni is an extraordinary masterpiece and discovery in the ancient art history of South Asia (even the entire history of Buddhist art), inspiring the image of the Bodhisattva in the Boudhanath Stupa.

When studying the art and culture of various communities in the Himalayan region (whether in Nepal or Tibet), it is important to remember that although Buddhism originated in northern India, it only developed a unique face after assimilating the diverse local cultures of various regions (especially in Tibet). The worship of Avalokiteshvara (and the statue of Avalokiteshvara) demonstrates the greatness of this assimilation process, and one should not forget the outstanding contributions of the Newar people in this process. While there are many myths and texts about it, only art can quickly spread spiritual ideas to different regions. The worship of "Avalokiteshvara" not only attracted artists from the Newar community, but also influenced the people of Tibet in their expression of the sublimity of wooden sculptures.

18th century, collected by the Beilis family

Detail: Wooden Buddha statue offered by King Utpalaka

"Dunhuang Ancient Tibetan Manuscript PT.239" (excerpt)

Stored in the National Library of France

People are immersed in the various distractions of the world, and the author will end with a passage from a Buddhist scripture found in the ancient Dunhuang manuscripts (see PT.239): "If you fear falling into depravity, remember the Bodhisattva Avalokitesvara, who will protect you from the great hell. Remember his name and pray to him. Recite his mantra and seek refuge in him, and you will be liberated from that dreadful place." It should be noted that the grand image of Avalokitesvara may serve as the main deity in a temple or as a attendant Bodhisattva of the central Amitabha Buddha. Nevertheless, it remains one of the earliest examples from South Asia, reaffirming the important role played by the "Pure Land worship" in the history of East Asian Buddhism.