Tibetan Scroll Painting "Pilgrims and the Holy Crystal Mountain"

Taboos that cannot be scaled

"Why can women not climb the pure crystal mountain?" This question was raised by Professor Toni Huber from Humboldt University in Germany in a 1994 article. The crystal mountain in question refers to the Zari God Mountain(དག་པ་ཤེལ་རི) in the Shannan region of Tibet, which in Tibetan means "pure crystal". Described in "The Light of Dabashe Ri": "The pure and luminous Dabashe crystal mountain, like the palace of the Buddha of the Sambhogakaya, the mandala of the self-arising secret wisdom, a brief discussion of the layout of Zari." As one of the twenty-four great sacred mountains in Tibetan Buddhism, its main peak is said to be the location of the Vajra Throne of the Pure Land of Sukhavati, where many sacred monks like Padmasambhava and Tsongkhapa have left their footprints through their practice. In the 12th century, the Kagyu sect high lama Zhabje Kargye Yeshe Dorje(གཙང་པ་རྒྱ་རས་ཡེ་ཤེས་རྡོ་རྗེ) practiced here, praising it as a realm of enlightenment. Since then, countless devotees have flocked from all directions to worship this sacred mountain.

Shengle Golden Vajra Pagoda City

New York. The Metropolitan Museum of Art.

There are three main routes for pilgrimage to Mount Kailash: the summit circuit around the main peak, the mid-level circuit covering side peaks and valleys, and the valley circuit which goes further away from the main peak, passing through the surrounding rivers and canyons. The pilgrimage journey around the Crystal Mountain is highly attractive to believers, as the sacred mountain is rich and pure, offering great benefits for cultivating virtue. The route closer to the summit "altar city" allows pilgrims to accumulate more merits.

"Tibet Map of Mount Tsari Pilgrimage Sites", held by the British Museum

However, such a magnificent activity excludes women. Huber found in her research that almost all women, whether secular or nuns, are prohibited from using the top loop of the mountain and the majority of the middle loop. They are only allowed to worship through the canyon loop around the periphery of the sacred mountain, accumulating some merit by exerting double the physical effort and gazing at the distant main peak.

Tsari Women's Pilgrimage Route

( ཙ་རིའི་སྐྱེ་དམན་གྱི་སྐོར་བ། The Pilgrimage Route of Those of Humble Origins)

Here is Huber's translation of a Western traveler's diary:

"The other place they worship is called Tsari, where groups of monks and women go to circumambulate the base of the mountain... For any woman, even a nun, to go to the top of the mountain is considered a sacrilege; and there is a prohibition, they must not cross a certain point." (Ippolito Desideri, 1720)

Italian missionary Ippolito Desideri (1684-1733)

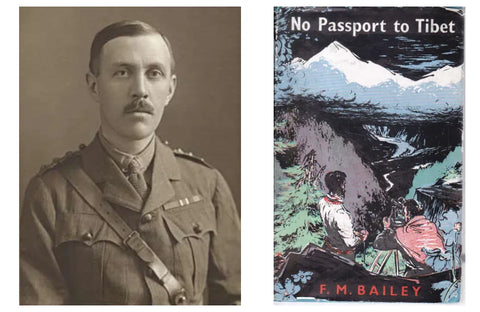

"Women are not able to perform the small circumambulation (i.e. through the mountain ridge), as the route crosses the Chomo La mountain pass, which is taboo for women. However, some will walk to the mountain pass and then return, in this way gaining a little bit of merit allowed by the taboo. ...Women are prohibited from continuing on the first stage of the middle circuit. ...On the first day, I hiked five miles up the mountain, reaching Lapu, where one of our accompanying women was sent back because of her gender. ...Chomo La mountain pass, 16,000 feet. No women are allowed to cross this pass. ...Coming down from Shang-lu, we descended 3,000 feet to Tongtang, which is a rest station in a forest of spruce trees. We found a woman in charge of the rest station, but women are not allowed to continue on the road between Chomo La pass and this rest station, as they are excluded from the pilgrimage route." (Fredrick Bailey, 1913)

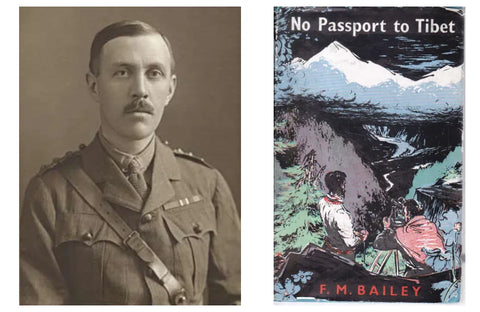

Frederick Marshman Bailey (1882 – 1967)

Bailey previously served as the British Commercial Commissioner in Gyantse and the Political Officer in Sikkim, where he conducted covert operations in the Tibet region. The McMahon Line was delineated based on Bailey's exploration in Tibet.

Zhuomara and the Snow Monster.

Huber points out that, due to the low priority given to female themes among traditional Tibetan writers, the specific reasons why women are not allowed to ascend sacred mountains are not recorded in existing Tibetan literary texts. However, clues can be found in oral traditions:

One relates to a legend about a goddess, Zhoma La(སྒྲོལ་མ་ལ་), who wanted to judge the morals of men and women, so she lay on the path leading to the mountain peak. One day, a man passed by and found the goddess, disguised as a paralyzed old woman, blocking the way. He politely asked the goddess to move aside. She replied, "My brother, I am so powerless, I cannot move; if you have pity on me, please find another path, if not, then cross over me." Upon hearing this, the man chose a different path. Soon after, a woman passed by and also saw the goddess, and told her to move aside; the goddess gave the same reply, but the woman still crossed over her. From that day on, women were forbidden to pass through there, as they would instantly die if they did, and the mountain pass came to be known as Zhoma La.

Dukkar corresponds to the Tara in English.

Another widely known rumor involves the daughter of a noble government minister who, upon hearing that women were not allowed to circumambulate Mount Kailash through the middle and top circuits, decided to disguise herself as a man and cross the Dolma La pass to circumambulate within the restricted area of the sacred mountain. Eventually, she reached a rest stop where she boasted, "Women cannot complete the pilgrimage is just nonsense!" She suddenly disappeared from the rest stop that night. A giant hairy beast called Migöd (man-ape) stealthily captured her, pulled down a large tree, split the trunk open, hid her body in the crevice, and then sealed the trunk before throwing it back. When her body was found in the tree trunk, she was already dead. It is believed that this punishment was carried out by the guardian deity of Mount Kailash, manifesting in the form of a beast.

These two intriguing rumors, without exception, portray secular women as arrogant and disrespectful, reflecting the troubling gender discrimination present in pilgrimage rituals and further revealing the imbalanced power dynamics and distribution in Tibetan society under traditional culture.

The legendary Yeti, also known as the Abominable Snowman

Gender Views behind Language

From the perspective of traditional Tibetan society, men are considered as representatives of respect, humility, and caution, and therefore more likely to receive favor. In contrast, women's characteristics are summarized as rude, proud, arrogant, and jealous, and thus must be constrained by men to avoid angering the gods. The formation of these stereotypes is related to the power distribution in ancient Tibetan society. In traditional society, Tibetan women are not only responsible for household labor, but also for agricultural and pastoral work. Even if a few noble-born women can escape from the burden of physical labor, they have no opportunity to enter the political circles considered as male privileges. In traditional society, men have the opportunity to become politicians, landlords, or monks. Women, on the other hand, are often limited to the social role of "women".

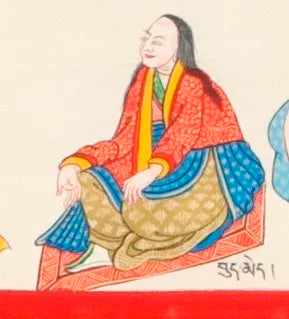

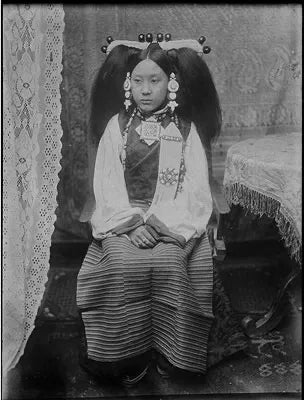

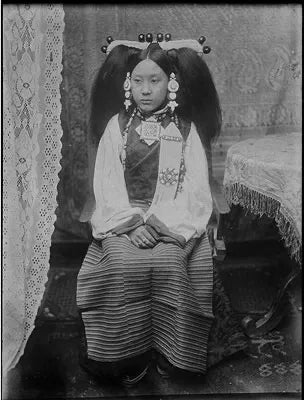

Noblewoman སྐུ་དྲག་བུད་མེད།

Noblewoman སྐུ་དྲག་བུད་མེད།

This imbalance in power distribution is also directly reflected in the language. Anthropologist Barbara Nimri Aziz was one of the first anthropologists to focus on Tibetan women, and she explained the gender concepts that may be reflected in the Tibetan language. In Tibetan, the common term for "women" and "wives" is "སྐྱེ་དམན", which is not a new term, slang, or regional usage, and is widely used in both early texts and modern vernacular. The literal meaning of "སྐྱེ་དམན" is "of low birth", and this surprising interpretation is not buried in the distant past; anyone who uses or hears this word can accurately tell you what it means. As for "men" or "husbands", there are no equivalent terms with discriminatory connotations. Men are referred to as "ཁྱོ་ག", "སྐྱེ་པ" or "བུ", with "ཁྱོ" carrying a meaning of bravery and nobility.

Noblewoman སྐུ་དྲག་བུད་མེད།

In Tibetan pronouns, there is also a clear gender difference. For example, "མོ" can represent "she" as well as be used to refer to poor women and female animals, meaning "it" when referring to animals, such as prostitute (ཁྱི་མོ), mare (རྟ་མོ), ewe (ལུག་མོ), sow (ཕག་མོ), female demon (བདུད་མོ), and so on. Due to its inherent discriminatory connotations, "མོ" is never used to refer to mothers, noblewomen, or goddesses.

Tibetan Shepherdess འབྲོག་མོ་

The corresponding suffixes for males, "ཕོ" or "པོ", are not widely used like the pronoun "ཁོ" for males. "ཁོ" is usually expressed as "he" or "him", and these terms are only occasionally used for women when showing respect. In general, they are never used to address animals, meaning "it" or "they". And there are no special pronouns for poor males, male servants, or minors.

Low caste དམན་རིགས།

In addition, in slang, women are also referred to as "བུད་མེད" (undismissable) and "ནག་མོ" (black woman). If language to some extent reflects the power dynamics in society, then these terms should raise our awareness of the severe gender disparities in Tibetan culture.

The Myth of the Witch

"The existence of the principle of equality does not automatically translate into an equal society. The widespread lack of egalitarianism in Tibetan society indicates a loss of primary Buddhist principles, and has negative effects on women in terms of socio-economic and psychological aspects." - Anne Klein (1985)

From a religious perspective, women in Tibetan regions are still not treated equally. Despite the allowance for female ordination in Buddhism, and even the importance of female practitioners in Vajrayana, women are still viewed as impure, contaminated beings by many male monastics.

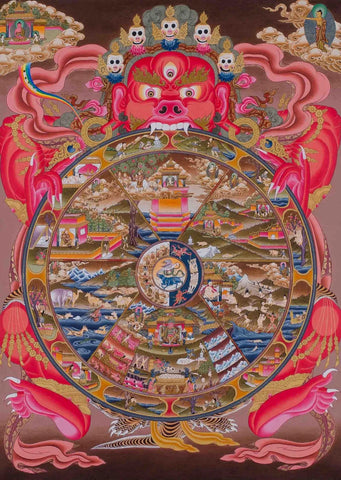

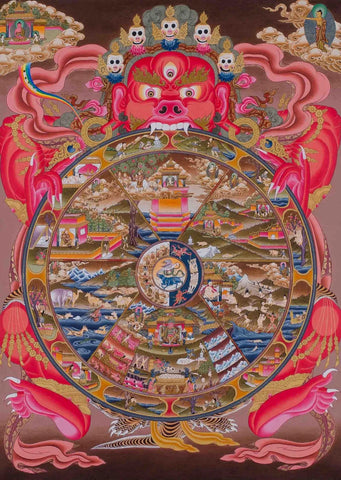

The six realms of reincarnation diagram

THANGKA MANDALA Buddist art gallery

Some scholars believe that one of the reasons for this bias is that in the cycle of rebirth (Saṃsāra), women are inherently responsible for childbirth and are therefore seen as the key role in maintaining the cycle. To some extent, they seem to be unable to escape the constantly revolving wheel of karma, making it difficult to break free from the shackles of suffering, and even bearing some kind of sin for the operation of the cycle. This also explains why in many areas of Tibet, women who are pregnant or menstruating are forbidden to enter sacred mountains.

Localized: Outer circle female birth symbolizes "birth" in the twelve links of dependent origination ( sanskrit. Jati ).

The derogatory term mentioned earlier, "ནག་མོ" (black woman), is a manifestation of this stigmatization. Black color is always associated with impurity, negativity, and evil, while white color is related to purity and virtue. Therefore, in Buddhism, good deeds are also referred to as white deeds (དཀར་ལས་). In the epic of King Gesar compiled under the influence of Buddhist narratives, there is a passage that goes: "When the earth is turned black by groundhogs, when thieves tarnish the reputation of the tribe, and when black women (ནག་མོ) lead men astray towards darkness, that's when the pure white teachings will prevail."

King Gesar and the Demon

Another story about a witch goes like this: It is said that a macaque was practicing in the snowy land. The macaque focused on practicing bodhicitta and understanding emptiness. At this time, the rock witch (Raksha) guided by karma appeared, trying to tempt him with words, changing into a woman's attire to seduce him, and proposing to marry him. However, the macaque who was focused on practicing dharma refused the witch's temptation. The witch then threatened the macaque, saying that if they couldn't become one, she would become a demon's companion and harm the creatures in the snowy land. For the benefit of all beings out of compassion and to avoid creating negative karma, the macaque had no choice but to marry the rock witch and together they gave birth to the earliest Tibetan people.

Witch and Monkey

In "The Chronicles of the Kings of Tibet", it is recorded: "The people of this snowy region are descended from a father who is a monkey and a mother who is a demon. Therefore, they are also divided into two types of temperament: those with the nature of the father monkey bodhisattva are gentle in temperament, firm in faith, compassionate, diligent, fond of virtue, kind in speech, and skilled in discourse. These are all characteristics of the father. Those with the nature of the mother demon are greedy, strong-willed, engage in commerce, seek profit, harbor strong enmity, enjoy mocking others, are brave and agile, indecisive, volatile, burdened with many worries, quick to anger, and prone to jealousy. These are all characteristics of the mother."

In later versions of this myth, the demon mother is considered to be an incarnation of the Indian goddess Tara (or the Buddhist mother of liberation), while the monkey is considered to be an incarnation of the Bodhisattva Avalokiteshvara, embodying compassion. The description of the different traits inherited from the mother and father in "The Chronicles of the Kings of Tibet" provides a glimpse into the moral burden placed on women from the perspective of Tibetan Buddhism.

Image of a Rakshasi woman holding a human bone and a kapala skull cup.

The second story about the witch: In ancient Tibet, demons ran rampant, and when Princess Wencheng entered this land, the temples she built were often destroyed by demons. Through divination, she discovered that the entire Tubo land resembled a lying witch demon (སྲིན་མོ). The Dragon King Palace in Lhasa lies in Raomoqi, while Lake Otang is the heart blood of the witch. The three peaks surrounding Raomoqi symbolize the witch's two breasts and her lifeblood (སྲོག་བརྩ). The eastern cape troubles the west, the west troubles the east, the south troubles the north, and the north troubles the south. In order to convert Tibet to Buddhism, Songtsen Gampo followed Princess Wencheng's advice and built thirteen temples in Tibet to suppress the witch demon, bringing peace and tranquility to the land.

Tibetan Town Demon Map

Harvard University professor Janet Gyatso believes that the rokshasa woman in this story represents a primal chaotic feminine force that is not welcomed by Buddhist power. Describing the existence of such a colossal witch evokes memories of the barbaric origins of the Tibetan people. For Tibetan women, she symbolizes a more resolute trait compared to some women in their Asian neighbors, displaying a stronger and more independent sense of self. The power of women is so strong that the male power structure in Tibetan mythology must take enormous measures to control this female presence... She may be ancient, perhaps even chaste, but she is definitely not passively waiting to be conquered. In the face of foreign cultures, she causes various disturbances, requiring widespread Buddhist architecture and male narratives to suppress her.

female demon (rakshasi)

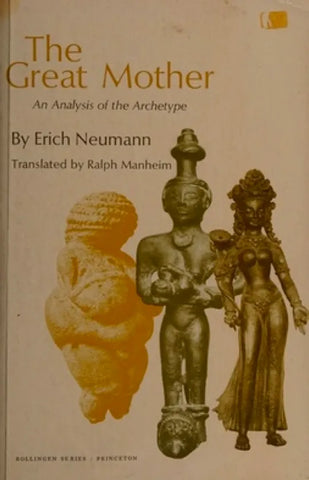

Through these two myths, it is clear that the Rakshasi woman, as a primitive deity native to Tibet, occupies an important position in the earliest origin myths and Bon religion stories of Tibet. Her existence may symbolize prehistoric Tibet, which, like other civilizations, may have gone through a stage of a matrilineal society. Greece's Earth goddess Gaia; Hawaii's volcano goddess Pele; Japan's unclean underworld goddess Izanami. These myths reflect the worship of the "Great Mother" in various civilizations in the prehistoric society and the attachment to female power structures. This worship of women is often related to primitive fertility worship and is an expression of collective consciousness in human society in its infancy. (Gustav Jung)

Erich Neumann,The Great Mother: An Analysis of the Archetype

The rise of male power structures was accompanied by the deprivation of the primitive sacredness of women. Many civilizations engaged in the modification of myths to eliminate the original sacredness of women. In Tibet, the introduction of Buddhist narratives became a crucial turning point, portraying the Tibetan mother goddess as a fierce and greedy female demon, and depicting the original feminine spirit as a disruptive rakshasa. In this process, society gradually moved from chaos to stability, and women became sacrificial objects.

Zha Ri Mountain

Ne Dakpa Shelri, Takpa Shelri, Tsari

Since the 1980s, more and more scholars from both the East and the West have turned their attention to the study of women in Tibetan areas. We are pleasantly surprised to find that despite facing dual pressures from secular and religious forces, Tibetan women continue to drive the historical progress and social change in Tibet with outstanding courage and resilience.

In the long history of Tibet, there are no lack of women who have emerged in the "male privilege domain". Their success often comes with great sacrifice. For these women, the Crystal Mountain may be a distant and unattainable dreamland, but their resolute and pure qualities, like the mountain, will be engraved in the pristine soil of this land by history.

Some famous Tibetan women.

Mei Lu · Chi Ma Lei འབྲོ་ཟ་ཁྲི་མ་ལོད (?—712年)

After the premature death of her husband, King Mangsong Mangzan, the Queen of Tubo became the de facto ruler of the Tubo Empire from 676 to 689, thwarting the plots of the Garshi clan and successfully protecting her son, King Trisong Detsen. In 704, King Trisong Detsen passed away, and the young prince, Prince Chide Zan, ascended to the throne, with Queen Jarmazar acting as regent once again in her capacity as grandmother.

Yikisojia (ཡེ་ཤེས་མཚོ་རྒྱལ)757-817 AD

Princess Kyabje Yeshe Tsogyal, originally the consort of the Tibetan Emperor Trisong Detsen, later became the principal disciple and consort of the Nyingma master Guru Padmasambhava. She is an exceptional Tibetan Buddhist female teacher and treasure revealer. Guru Padmasambhava referred to her as "my equal." After exiling to remote regions, she continued to practice the Dharma and attained mastery in the practice of the Eight Sadhana Teachings, particularly the practice of Vajrakilaya. Yeshe Tsogyal preserved and disseminated Guru Padmasambhava's teachings and is considered the lineage holder of the Nyingma teachings and an emanation of the dakini Vajravarahi. She is highly revered in both Nyingma and Kagyu traditions.

Sangdo Dolma (བསམ་སྡིང་རྡོ་རྗེ་ཕག་མོ)

Her original name was Salong Zhenma, the highest-ranking female practitioner in Tibetan Buddhism and the abbess of Sangye Monastery. Her previous incarnation was Vajravarahi. The first Sangye Rinpoche, Kunga Zomey, received teachings from Perton Chola Langjie and Tangdong Jiebu, and was recognized by Tangdong Jiebu as the third reincarnation of Salong Zhenma. She founded Sangye Monastery in the 1440s in the Yarlung area. The Sangye Doji Pab system was established after her passing and is ranked as the third highest reincarnation system after the Dalai Lama and Panchen Lama, receiving recognition from the Tibetan government and the Qing Emperor. The lineage continues to this day with the twelfth reincarnation.

Machig Labdrön(མ་ཅིག་ལབ་སྒྲོན)

1055-1149

Machig Labdron is a female Buddhist master in the Tibetan tradition and the founder of the lineage of female lamas. She studied under Geshe Zhaba in her early years and later met the founder of the lineage, Padampa Sangye, who praised her as the "embodiment of the four great wisdoms, an emanation of the mother of the Buddhas in the practice of empty conduct." After marrying and having children, she left home at the age of 34 to receive empowerment from the master Sönam Lama, taking the name "Dorje Wangmo." Following the teachings of Padampa Sangye, she established the lineage of female lamas at the age of 37, setting up the main monastery of Sangyé Karmo and transmitting teachings to her disciples. She passed away in 1144 and is honored as an incarnation of the wisdom dakini.

They are great and difficult.

Noblewoman སྐུ་དྲག་བུད་མེད།

Noblewoman སྐུ་དྲག་བུད་མེད།