The Divine Gift of the Celestial Maidens: An Explanation of Himalayan Grapes

"Blue Lapis Lazuli Tibetan Medicine Thangka: Categories of Medicines"

In the first half of the 20th century, the Tibetan Medicine Bureau of Menzikang in Lhasa

Local: Licorice slices - Grapes - Sea buckthorn fruit

"Grapes have a sweet taste, can treat lung heat and pediatric lung diseases, etc."

ལོངས་སྤྱོད་མོད་ཀྱང་ལས་ངན་གྱིས།

འཇུངས་པས་སྤྱོད་པའི་རང་དབང་མེད།

རྒུན་འབྲུམ་སྨིན་པ་ཟ་བའི་ཚེ།

ཁྭ་ལ་མཆུ་ནད་རྒྱུན་དུ་འབྱུང།

Wealth gained through evil means is short-lived,

Misers will find it hard to enjoy blessings,

When the grapes are ripe,

The crow's beak will be sore.

From "The Sayings of Sakya"

(ས་སྐྱ་ལེགས་བཤད་)

Written by Sakapanditadas

(ས་པཎ་;1182-1251)

Note: The fable of "The Grape and the Crow" has long existed and been widely spread among various religious communities in South Asia.

It serves as a reminder for people to pay attention to cause and effect and to do good deeds.

Buddhists and Jains use this tale to illustrate the evils of selfishness and the importance of caring for all sentient beings.

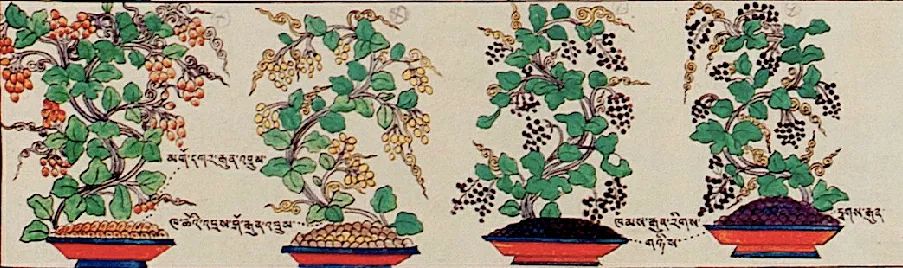

"Blue Lapis Tibetan Medicine Thangka: Earth Medicine, Wood Medicine, and Plain Medicine"

In the first half of the 20th century, collection of Rubin Museum

Detail: Kashmir White Grape - Kashmir Valley Grape

Tibetan Kandar Region Grape Two Types - Tibetan Tabo Grape

Kashmir white head grape (མགོ་དཀར་རྒུན་འབྲུམ་)

Fruit color red yellow and relatively large in size

Kashmir valley grain grape (ཁ་ཆེའི་འབྲས་ཤོ་རྒུན་འབྲུམ་)

Fruit color yellow like peas and seedless

Tibetan Kang grape (ཁམས་རྒུན་རིགས་གཉིས་)

Fruit color varies green, red and purple and relatively large in size

Tibetan Tabo grape (དྭགས་པོའི་རྒུན་འབྲུམ་)

Fruit color bluish and relatively large in size

* "Tabo" roughly includes parts of present-day Lhoka Lhoyul and Gyaca counties

(or also some parts of Lhoka Sangri county)

The kind shepherd, threatened by a demon, was forced to leave his homeland. Exhausted, he collapsed on the road, on the brink of death. In his final moments, he saw a vision of the cow that had once been his companion. The cow pressed her udder against his lips, and a sweet milk flowed into his mouth. But when he slowly opened his eyes, he saw not a udder, but instead fruits that resembled cow's nipples.

In popular folktales from the Kashmir region and northern India, grapes are likened to cow's nipples; interestingly, in the Tibetan language, grapes are also referred to as cow's nipples (བ་ཡི་ནུ་མ་). The prominent Gelugpa sect lama and local historian Gonchok Sonam (དཀོན་མཆོག་བསོད་ནམས་; 1910-1987), who served as the President of the "Ladakh Buddhist Association" from 1961 to 1974, also documented this story. He determined that the early grape culture in Tibet is related to Central Asia, and considered the grapes in the story as sacred objects given by the goddess of fruit to offer nourishment. (There are indeed stories in Tibetan culture that personify grapes as female).

In Tibetan, grapes are generally referred to as རྒུན་འབྲུམ་(rgun ‘brum) or རྒུན་འབྲུ་(rgun ’bru), and in some early texts and secular literature, they are even written as དགུན་འབྲུམ་(dgun ‘brum) or རྒུ་འབྲུམ་(rgu ‘brum). There has been considerable debate in academic circles about the etymology of the Tibetan word for "grapes," with three main viewpoints: 1. The Tibetan word for "grapes" may have a Central Asian or North Asian origin; 2. The Tibetan words rgun and ’brum/’bru can both mean "grain" or "particle"; 3. The Tibetan word rgun can mean "prosperous" (based on affixation rules), and when combined with ’brum/’bru meaning "grain," it could be interpreted as "prosperous grains." It is worth noting that in the future, attention may also need to be paid to the term འབའ་ཤ་(’ba’ sha), which is used to refer to black grapes from Ali or other western Tibetan regions.

"Awakening wine bottle, wine glass, and rhyton"

During the Tubo period, in the collection of the Cleveland Museum of Art

(some of the artifacts are marked as belonging to a private collection)

The above vessels are decorated with vine patterns and wild animals

* "Rhyton": a type of horn-shaped cup popular in Eurasian countries.

"The Song of the Tibetan King Chokrab"

Collected by private institutions at the end of the 20th century

The cultivation techniques of grapes, grape beverages (including grape juice and grape wine), and the winemaking process constitute the core content of grape culture studies. Based on existing literature and archaeological reports, it is known that the Tibetan plateau has had mature grape cultivation techniques (predominantly from the west) since the imperial period, and the history of grape beverages in the region can be traced back to the Tubo Empire period. The Tubo monarch Ralpacan, who was assassinated by his officials in 836 AD, became an important figure in discussions of grape beverages in later periods due to the fact that he was drinking grape wine (gungchang/gun kyems) before he was killed.

In the imperial history compiled in later generations, including ancient texts found in Dunhuang, wine became a part of the empire's memory, being used in religious activities and festive celebrations. Scholars also enjoyed tasting raisins and grape juice. After the disintegration of the empire, records of the nobility drinking wine continued to be found in the annals, such as ministers offering wine to members of the Renweiba family. The history of winemaking in Tibetan areas that is familiar to people today is often associated with French missionaries in salt wells (1865).

For Buddhists, grape juice (non-alcoholic) is a praised beverage by the Buddha himself, and is considered the sweet fruit offered by the Yakshas of the northern region (generally referring to the Kashmir region). In the writings of the Tibetan vinaya master Tsognyawa Serab Zangpo (13th century), it is recorded that the Buddha taught his disciples the whole process of eating grapes and making grape juice.

Not only that, the process of separating juice is also seen as symbolic of spiritual practice guidance. The disciple of Tsongkhapa, Lhodrak Namka Gyeltsen (ལྷོ་བྲག་ནམ་མཁའ་རྒྱལ་པོ་; lived in the 13th to 14th centuries), has elaborated on this. The separation of grape juice (or sugarcane juice) can also be related to the Buddhist concept of generosity, where the juice that has not been squeezed out does not mean it does not exist. Just as there is no grape without juice, the unseen karma of generosity does not mean it does not exist, and without a giver, there will not be the virtuous karma of generosity.

"The Northern Guardian King and his Attendants"

14th century, J. Paul Getty Museum, Asia Art Collection

Detail: Far left - Yaksha providing fruits and jewels

Far right - Northern forest and sweet river of the North.

"Transmission of Lineage: Lhodrak Namkajeub"

In the late 18th century, collected by David Nalin.

The glistening grapes of memories past